Jazz in the Sanctuary: A historic look at sacred musical spaces in Philly and beyond

From a field holler to Marvin Gaye’s “make me wanna holler,” music is historically a source of solcae for African Americans in their struggle for equal rights and social justice.

Rooted in the black experience, jazz both has been a sanctuary and found sanctuary in the church. Indeed, the church was one of the safe places where jazz was played during Philadelphia’s jazz heyday in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s.

In 1939, Philly-born Billie Holiday told the nation that “Southern trees bear a strange fruit.” In 1955, Louis Armstrong transformed Fats Waller’s song of unrequited love, “(What Did I Do To Be So) Black and Blue,” into a civil rights anthem. Holiday, Armstrong and Waller were members of the Harlem Renaissance.

Jazz musicians and the jazz culture played a key role in breaking down barriers to racial integration. Nat Segal’s Downbeat Club, located at 11th and Ludlow streets, was the first integrated nightspot in Center City. So it was fitting that in his invocation at the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Pastor A.R. Bernard Sr. noted how artists helped ignite the civil rights movement.

Jazz musicians and the jazz culture played a key role in breaking down barriers to racial integration. Nat Segal’s Downbeat Club, located at 11th and Ludlow streets, was the first integrated nightspot in Center City. So it was fitting that in his invocation at the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Pastor A.R. Bernard Sr. noted how artists helped ignite the civil rights movement.

They called themselves the New Negro Movement, better known as the Harlem Renaissance, creating their own literature, art, music, theater. They artistically and intellectually challenged the pervading black stereotypes. From this generation emerged names like W.E.B. DuBois, Alain LeRoy Locke, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, Fats Waller and Duke Ellington.

White America experienced it and said, “Ooh, we like the style of these people.” So they enjoyed it, adopted it, integrated it and exploited it. And the popularity of black style and culture soon spread throughout the country. But it was not enough for black folks to be artistically admired. Blacks wanted and demanded full participation in the social, political and economic life of American society. And that attitude set the stage for the civil rights movement of the 1950s and the 1960s.

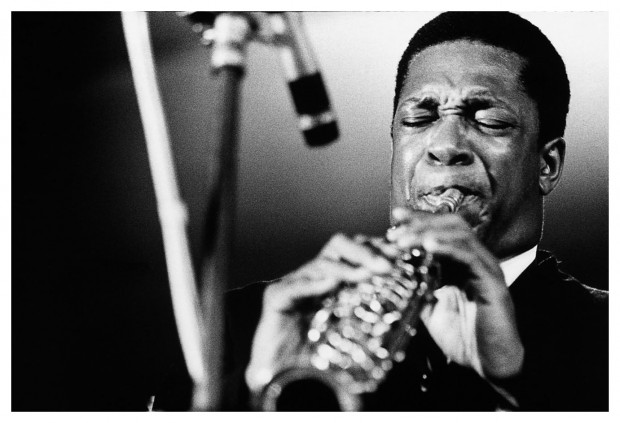

Three weeks after the historic 1963 march, a bomb exploded in Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church killing four girls. The act of domestic terrorism moved John Coltrane, the grandson of prominent African Methodist Episcopal ministers, to compose “Alabama.”

Deeply religious and spiritual, Coltrane likely sought comfort in the churches of North Philly, where he lived from 1943 to 1958. Trane’s next-to-last performance in Philadelphia was held on Nov. 4 Nov. 6, 1966 at the Church of the Advocate. (His last Philly engagement was on Nov. 11, 1966 at Temple University’s Mitten Hall Auditorium; listen to a performance of “Naima” from that concert here.)

The historic church is bringing jazz back. Kemah Washington, Senior Warden at the Church of the Advocate, told the Philadelphia Tribune:

During the ‘60s, we had a lot of jazz artists that used to come through the church. John Coltrane probably being the top name, and Max Roach. We had great community participation too. A lot of guys they would come and get on stage, and they would … what you call, share. We’re trying to mimic that again. There’s a need for the arts in our community, and we know that’s how young folks can express themselves. They need to be able to express themselves, and get some of their frustrations out, and work things out.

The divine sound can be heard at the Lutheran Church of the Holy Communion on Chestnut Street. The Jazz Vesper service is conducted at 5:00 p.m. on the third Sunday of every month. And if you really want to get your praise on, head over to South Philly and check out Jazz, Jive & Praise at Tindley Temple.