Earthquaking Ecstasy at the Dawn of 2014: PhillyBloco’s Annual New Year’s Dance Party

Forget the intermittent spring weather, more likely to incubate a flu than the inclement snow and iciness from the preceding week. That’s your stereotypical Philadelphia winter, but just put it out of your head for a second.

Imagine yourself transported to a far-off tropical country with beautiful white-sand beaches and calming whispers of breezes caressing your hair. Suddenly, your tranquility is broken by thunderous gut-shaking crashes, but in the exact second you realize that you’re not dying in an earthquake, you realize that you cannot stop dancing. Lines of dancers and drummers in awe-inspiring processional clothing cascade down the street, overwhelming every one of your senses with a blend of samba, funk, and reggae.

Sounds like the greatest party of all time, right? Well, even if they can’t promise Rio-style sunshine, PhillyBloco still bring their A-game to every one of their shows. Their New Year’s show at World Cafe Live, the third of its kind, promises to sell out as quickly as every other full-body experience they stage throughout the year.

Take a look at any of their videos, and you’ll get a sense of why they’ve gained a fast reputation for insanely fun shows. For those who love samba music and culture, they have some fantastic credentials – some of their members have studied with some of the best blocos (large samba bands, like theirs, with elaborate vocal and percussion ensembles that exist throughout Brazilian cities of all sizes) in Rio de Janeiro.

Traditional Brazilian instruments with trans-Atlantic (mainly West African and Portuguese) and native roots like the agogo (high-pitched bell) and caixa (Portuguese snare drum) dominate the sonic space, with popular Portuguese-language songs interspersed throughout their set.

But for the probable majority of their audiences, PhillyBloco might be their first exposure to this rich musical tradition. They needn’t be concerned, since samba’s percussive base sits comfortably alongside the reggae, New Orleans second line, and funk that PhillyBloco also incorporates into their music. They’ll recognize songs from folks like James Brown, and hopefully this unique spin will get them interested in digging further into something unfamiliar.

Like jazz in this country, samba is the child of a fraught and traumatic history that includes slavery (with Brazil receiving many slaves during the peak of the Atlantic slave trade), forced assimilation, and political repression. Also like jazz, samba continues to adapt with exposure to music from other parts of the world, and modern-day blocos incorporate unique spins on funk, reggae, hip-hop, and other music of the African diaspora.

However, samba achieved a cultural ubiquity throughout Brazil that jazz never quite did in the United States. Whereas most Americans might be able to name one or two jazz standards if pressed, Brazilians of all backgrounds participate in samba as ritualistically as they do soccer.

“Samba is life in Rio, and in Brazil, in a lot of ways,” explains Michael Stevens, percussionist and musical director of PhillyBloco, about the mission of what they do. “You need to really be on top of what you’re doing and do it correctly.”

“Doing it correctly” means conveying the authenticity that Stevens, percussionist and musical director, finds so necessary in his life pursuits. His encyclopedic knowledge of samba tradition and culture, informed by near-annual trips to Brazil, was built over two decades of musical exploration that began his freshman year at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. The liberal arts school, well-known for its undergraduate offerings in ethnomusicology, opened doors for Stevens into the world of samba.

“There happened to be a graduate student doing a dissertation on Brazilian music, and he was offering a samba percussion class. When I first heard samba, I was completely infatuated with it, and I ended up taking that class every semester until I graduated,” recounts Stevens.

PhilaBloco playing in the crowd | Photo by Dan Colavito

Today, Stevens’s life revolves around samba. Besides directing PhillyBloco, he also operates the Mt. Airy-based Unidos da Filadelfia Samba School, modeled after the samba “schools” or parade bands of Rio and Salvador da Bahia that manifest as the audio-visual spectacles most clearly associated with Carnival (like Mummers bands in Philadelphia, audiences have their own neighborhood- and social group-based loyalties to different schools). Through the Samba School, he offers community classes in Brazilian percussion and offers opportunities for novices to showcase their skills at various events (including some PhillyBloco shows). He also teaches Brazilian percussion as a for-credit class at UPenn.

PhillyBloco was built in 2008 around core drummers that he recruited from these classes, as well as musicians he encountered through his previous stint with fellow samba-fusion Alo Brasil (who put on a dynamite set at this summer’s XPoNential Music Festival). A number of these musicians, like fellow percussionist Ali Stumacher, came in with little-to-no performance experience.

“I hadn’t played samba before [Mike’s samba school class],” explains Stumacher, who initially met Stevens while both were students at Wesleyan. “I had no idea that this could’ve ever happened. Even now, when we play, I’m wondering, ‘How did I get here? I’m up on this stage with this amazing band!’”

The non-percussionists that round out PhillyBloco – horns, singers, and a nimble rhythm section – bring a wealth of professional and multi-disciplinary musical experience that ultimately shapes the fusion elements of the band’s sound. For keyboardist Dustin Beck, whose brother Jay splits lead vocals with the prolific Adwoa Tacheampong, the music’s links to the African diaspora make fusion much easier than one might think.

“I’ve always liked old rock n’ roll, like Jerry Lee Lewis. And I wanted to play solo piano, and New Orleans-style is a very specific kind of piano playing. A lot of rhythms of the Caribbean and Latin America are in New Orleans’ music,” says Beck. He is able to explore a very direct connection between New Orleans and Rio every time he plays with this band (he also plays with the Randy Lippincott Band at blues venues around the area).

From the outside, the project looks pretty difficult to pull off – nearly 24 musicians (and a few dancers, in keeping with the bloco tradition) on one stage, with half of them holding percussion instruments (insert your favorite drummer joke here) and all of them at varying levels of experience, somehow sustain a multi-lingual, organized chaos that threatens to run off the rails at every turn. Stumacher and Beck both attribute the group’s collective focus in large part to Stevens’s drive and leadership, as well as a deep mutual respect and admiration amongst members.

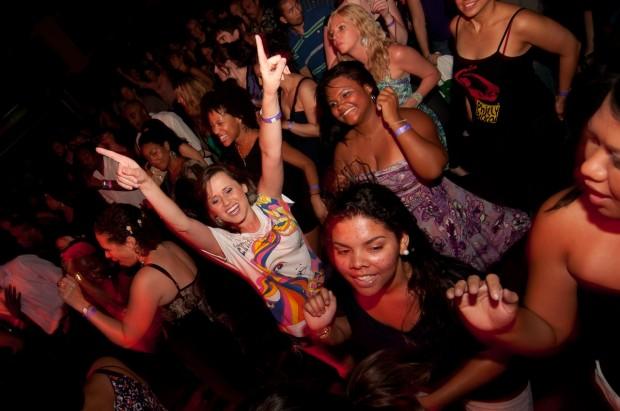

PhilaBloco crowd | Photo by Dan Colavito

“I think that Mike is so good that everybody respects him. He has done the work and can play everybody’s part.” explains Beck. “Every section of the band is just so pumped to be there, and it has this great family atmosphere whenever we play shows,” adds Stumacher.

Talking to these three is like meeting the most enthusiastic musicologists in the world, but without a trace of irony or overindulgence. Truthfully, these are people brought together by ecstatic love for this music that lives and breathes in an all-consuming live extravaganza. The joy of cross-cultural connection is what inspires PhillyBloco members to keep playing and engaging an increasingly-rabid following up and down the East Coast – a following that, as anybody who comes to their New Year’s Eve show will attest, is just as important as any of the people on stage.

“The crowd is a huge part of our show, and in Brazil, samba is a big deal,” adds Beck, “They have a culture that is built around samba, and that takes hundreds of people to work. The audience [in samba] is the most important part, and we have one the best ones around!”

PhilaBloco | Photo by Joel F.W. Price

PhilaBloco rings in 2014 at World Cafe Live on December 31, 2013 beginning at 9 p.m.; tickets to the 21+ show are $35 and available here.