Ambition Versus Expectation: What do performers owe their crowds?

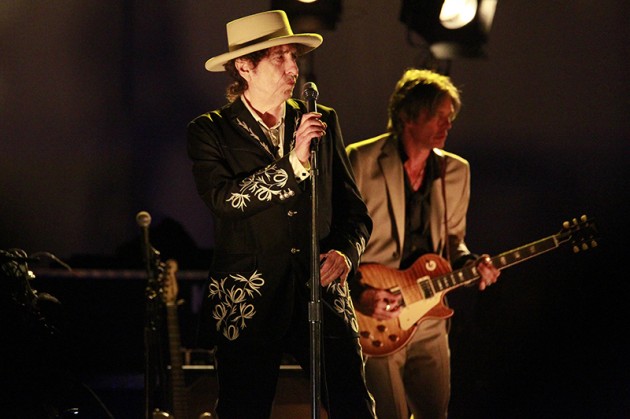

Confession time. The one time I saw Bob Dylan, I walked out.

His performance was disappointing, more than a little bit sad, and got me thinking about unspoken agreement between artist and audience. When a concert is so drastically different from the expectations behind it, did the crowd get shortchanged?

It was the XPoNential Music Festival two summers ago, the year of the colossal rain storm. I was soaked to the bone, sticking it out for my chance to see the American songwriting legend who was responsible for Blonde on Blonde and Blood on the Tracks and so so many more classics. I knew he wasn’t going to play the songs the way they sounded on the album; I knew his voice wasn’t what it once was. And I was okay with that, because I’m generally comfortable with artists taking artistic liberties – and let’s face it, Dylan was never a great singer.

But I wasn’t prepared for how bad it was going to be. A half hour or so into the set, the band – who seemed to all be skilled players, for sure – was in the middle of a wandering, free-form expanse while Dylan’s barely audible voice croaked indiscernibly along. At one point, he uttered something that sounded vaguely like “Pourin’ off of every page / Like it was written in my soul from me to you” and I realized, OH GOD, this is supposed to be “Tangled Up in Blue.” I gave up. I went home.

I’ve been thinking about that Dylan concert this week for a couple reasons; one, because he just played three nights at the Academy of Music and was reportedly quite good. And two, because I recently reviewed Lauryn Hill’s show at the Electric Factory and roughly criticized the crowd for doing exactly what I did during Dylan’s set.

Her DJ took the mic at about 10:55 to break down the run of show, and it was classic soul revue style: he was going to spin, then the band was going to come out and play, then the backup singers were going to come out, then Ms. Hill was going to come out. If you see Charles Bradley and his band, this is how it plays out; if you saw James Brown back in the day, it was how he rocked it too. Despite the DJ spelling this out, this sense of pageantry wasn’t popular among the curmudgeon-y group behind me either; they got impatient and began heckling from the get-go.

One has to wonder how much people knew about Hill as a performer in 2014 before buying tickets to the show.

Does this, I wonder, make me a hypocrite? Not exactly, I tell myself – my issue with Dylan was not the interpretive performance per se, but that he simply sounded bad. Hill’s interpretive performance, by comparison, sounded tremendous to my ears.

But a lot of people – at the show and online – disagreed, and a conversation about her artistic ambition (or hubris, depending on your read) versus the audience’s expectations sparked on The Key’s Facebook.

“There is a fine line between experimenting with your work, and not doing what the audience expects out of spite,” wrote Jesse Berdinka. “Lauren [sic] seems to be walking that line. … [She] IS an artist and she has rights, but she is also a performer and takes money to PERFORM.

“How much does an artist ‘owe’ to an audience who is paying them?” continued Berdinka. “If Lauren was working on a corner and just singing for the love of it, then ‘go with God.’ But she isn’t.”

Jamie Igou, another Facebook commenter, was a bit harsher in his criticism. “The show was complete garbage. The songs were unrecognizable. Lauryn appeared to be ‘on’ something. Disconnected from the crowd like we weren’t even there. The tempo of the songs were so fast you could not understand the words she was singing. … I was heart broken to see a musician I adored for so many years use her fans for a paycheck.”

So the takeaway here – its all subjective, obviously, and where I heard unbridled brilliance, others heard unlistenable rubbish. It was clearly a polarizing set. And polarizing performances like this are a staple of contemporary music history.

Alan Sparhawk of Low performs at The Current’s Rock the Garden festival | Photo by Nate Ryan via thecurrent.org

Miles Davis famously performed with his back to the audience and lashed out at his fans if they tried to get near him. More recently (on the lashing-out-at-fans note), Bradford Cox of Atlas Sound and Deerhunter responded to a Minneapolis heckler’s cry for “My Sharona” by playing the 80s classic by The Knack – for a straight hour, uninterrupted.

Also in Minneapolis last summer was Low’s infamous “Drone, not drones” performance. The band was on the bill at the Rock the Garden festival put on by the influential public radio station The Current, and rather than play a traditional set, they played a single song – “Do You Know How to Waltz?” from the 1996 album The Curtain Hits the Cast – for 27 dissonant minutes. At the end, frontman Alan Sparhawk said three words by way of explanation – “Drone, not drones” – a bumper sticker slogan criticizing the Obama administration’s support of unmanned aerial vehicles during international conflict.

The performance caused an uproar of frustrated fans at the festival and online. But Andrea Swensson of The Current wrote an essay in support of the band’s “audacity.”

A band does owe us something, no? At least from a social perspective, we expect them to put effort into their performance, to demonstrate their artistic talents to the best of their abilities, and to “earn” the spotlight that is cast on them when they step out of the shadows we cast on one another and up onto that stage. And in that regard, I would argue that Low did fulfill their obligation. They gave the crowd something unique, something unexpected, and something that provoked. Everything that happened after that was beyond their control.

For their part, Low’s fan base seems like the sort who (generalizing) might be more open to an abstract, artistic and unconventional set like this. Hill and Dylan, by comparison, may see themselves as artists first, but they are pop artists specifically. Meaning they have a wider range of expectations from a broader crowd, who might not be interested in being challenged. Pat Neligan of the Ireland-based blog AudioExchange writes:

Music critics often complain of “event tourists” – individuals who go to concerts for the fun, the crowd and to hear the hits. The ARTISTE is entitled to play what they want for however long they want. Put up and shut up you tasteless buffoons. I consider this attitude to be despicable. If you have forked out half a weeks wages to see one of your musical heroes, the least that they can do is play a few familiar tunes.

Neligan suggests a solution for the ambitious artist: one, realize that the crowd wants to hear some recognizable hits, and assure them that they’ll be in the mix after the freak-out session is done. In terms of setlist, this was the structure Hill took – her block of Fugees songs, while interpretive, was much more true-to-form. However, she did not warn the crowd that, don’t worry, the normal stuff is coming. Which makes sense, as it cannot be fun to hand-hold your audience…even if some of them might need it.

David Bowie with metallic wings during the Glass Spider tour. The stage production was intensive but fans wanted to hear the hits.

Talib Kweli has another solution. The rap icon who opened for Lauryn Hill at the Factory penned an essay about her earlier this year that I block-quoted in my review. To boil it down: “If you have a negative experience at her concert, go home, put on The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill and the next time she does come through your town, don’t go to her concert. Problem solved.”

A bit harsh, but that solution still sucks for the disappointed fan who already paid $75 a ticket to see her once. Maybe research into a performer’s track record is prudent for the easily disappointed? Some quick Googling would show you that Hill’s Philly set was not out of the blue; and if you went in expecting it, as I did, it was exceptionally good.

Which brings us back to Dylan. Mike Hogan, digital director of Vanity Fair, wrote a great piece about the modern Bob Dylan concertgoing experience for Huffington Post last year, and he hit the nail on the head: “Seeing Bob Dylan live at this phase of his career is a bit like bird-watching. You spend a lot of time waiting for something to happen, but if you’re lucky you experience an occasional moment of true magic.”

That’s not said as a criticism, that’s said from the perspective of an uber-fan who has seen Dylan 11 times. Continues Hogan:

I believe Dylan is following his muse, plain and simple. And why wouldn’t he? The muse made him famous at the ripe old age of 22. The muse gave him – and us – “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Tangled Up in Blue” and “Things Have Changed,” to name just a few of the many, many timeless songs he has composed. If the muse is telling him to play night after night, who is he to say, “Aw, thanks for the invitation, but there’s a dinner party in Malibu I don’t want to miss”?

That’s actually the deal almost everybody else ends up striking with the spirits of inspiration, but not Dylan. Seen this way, it’s almost sad how the Rolling Stones have burnished their act to such a sheen that the only question is which pop star Mick will pluck from the charts to help him seem relevant this time. Have they really lost their faith in spontaneity?

Like Hill, Dylan doesn’t spend a lot of time talking to his crowd, doesn’t assure them that the hits are coming. Nobody expected that he was going to close his opening night at The Academy with “Blowin’ In The Wind,” but it happened. “And here’s the bottom line,” Hogan wrote. “As long as Bob fucking Dylan is willing to play hide and seek with his muse on stage, for all to see, I’m going to keep on paying to see what happens.”

Ultimately, when a performer takes an audience’s money, what is the audience owed? A performance. That’s where the hard-and-fast rules end and the interpretation begins. Hill may not have played the songs the way I’m used to hearing them but she was onstage for two hours straight, singing and dancing. I coudn’t even begin to argue that she did not perform.

David Bowie’s 1980s fans may have hated his Glass Spider tour – which favored material from the much-derided Never Let Me Down to any possible other era of Bowie – but there’s no denying that the massive theatrical undertaking was, at its core, a performance. Maybe not the performance people wanted to see, but it was a performance.

Live music can work on two levels. It can work as a scripted and occasionally predictable experience – that whole debate about the Pixies and the role of the encore – but nevertheless an enjoyable one. But it can also be something unexpected and unique, and when artists enter that realm, that’s where the concertgoer needs to take a leap of faith. This could be a train wreck, I often tell myself in these situations. Or this could be amazing. Either way, I’m excited to see what happens.