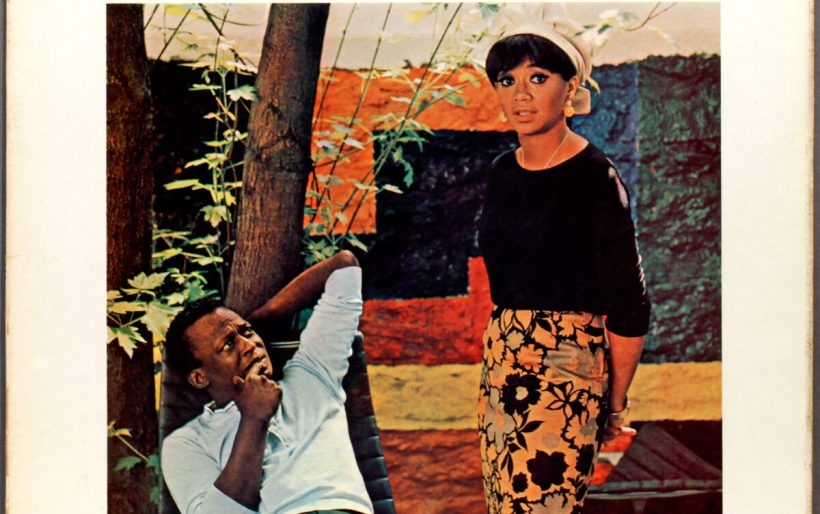

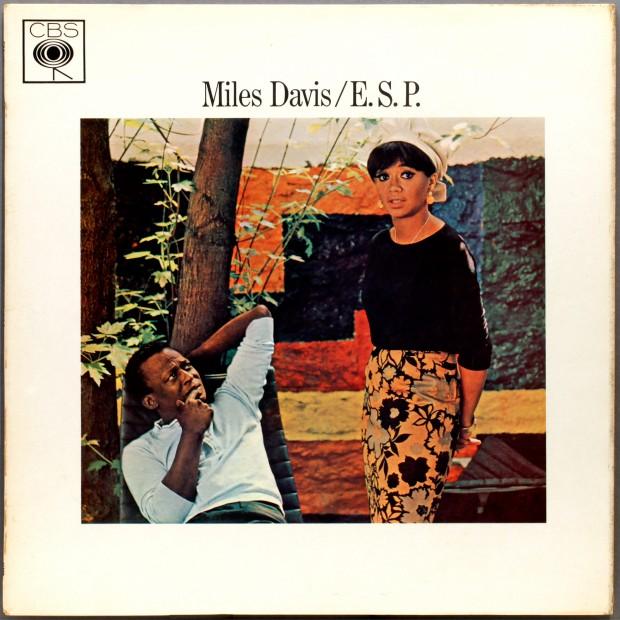

Miles Davis’ E.S.P.

Sleepy Hollow Time Travels: Revisiting 1965

Last time you heard from us at The Key, we Sleepy Hollow hosts were discussing some of our favorite albums slated for release in the coming months. All fans of a wide variety of music in place and time, we thought we would take a step back…fifty years, to be exact…and focus on just a few of our favorite recordings released in the year 1965.

Miles Davis’ E.S.P.

Miles Davis – E.S.P. (Columbia)

Like, well, every other year of the 1960s, jazz found itself in a difficult place in 1965. It is well-worn territory to discuss the music’s ever-dwindling audience, which was increasingly being replaced by rock and roll and soul for younger people searching for a new sound. Jazz itself was becoming ever more compartmentalized while the revolution of the avant-garde, spearheaded by Ornette Coleman a whole six years earlier, was in full swing. The year would arguably come to be defined by A Love Supreme, John Coltrane’s revelatory four part suite released in February of 1965 that would cement him as the era’s great innovator, and signify the musical path he would thus take, aggresively pushing boundaries until his death in 1967.

For Miles Davis, his former employer, aggression (at least musically speaking) would not play a role until years later with his headlong dive into fusion. By 1965, Miles had assembled what would become known as his “second great quintet,” an astounding group of younger musicians that included Tony Williams (drums), Ron Carter (bass), Wayne Shorter (drums), and Herbie Hancock (piano). Whereas other groups were experimenting with the style known as “free jazz,” Davis played a music more steeped in tradition that, by consequence of the time it was being made and, most importantly, by Davis’ bandmates, was increasingly free. E.S.P.’s brilliance comes in this balance to offer something groundbreaking while still managing to ring with familiarity. Save for the album’s most dissonant track, side-B opener, “Agitation,” the back half of E.S.P. serves as one of Miles’ most engaging statements, with over seventeen minutes of exquisite performance in the ballads “Iris” and “Mood.” With their startling fluidity, the quintet begs the listener to engage in an act of musical voyeurism–like overhearing a sublimely beautiful, intimate conversation that we are lucky enough to have preserved in recorded history for all time.

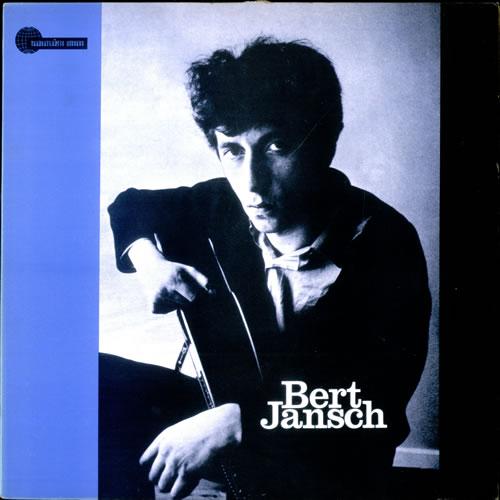

Bert Jansch’s self-titled album

Bert Jansch-Bert Jansch (Transatlantic)

It would be years before Bert Jansch, the Scottish guitarist now synonymous with the British Folk movement, would reach his creative apex alongside John Renbourne with their group Pentangle, an exceptionally gifted hybrid whose ability to seamlessly blend jazz and folk would not be equaled nor ever even substantially imitated. Still, his 1965 self-titled release remains one of the finest of his five decades-long catalogue. Though it contains the poignant “Needle of Death,” a pitch black portrayal of heroin overdose and, arguably, Jansch’s most enduring composition, much of the album resides more firmly within the wayward acoustic blues tradition, albeit with a more progressive lean that holds true to Jansch’s western European upbringing. One can only wish that “Finches” went on at least another minute or two, but songs like “Oh How Your Love is Strong, “Rambling’s Gonna Be the Death of Me” and the instrumental “Running from Home” are fully realized examples of how far the movement had come by the mid-’60s, and reflects the rich heights it would reach in the following years. This is acoustic music at its absolute best.

Nina Simone – “I Put a Spell on You” (I Put a Spell on You; Phillips)

The recording of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ 1956 composition “I Put a Spell on You” is one of the great stories of early rock and roll and rhythm and blues, the short version reading that the session culminated in Hawkins growling into the microphone under a drunken stupor brought on by his own producer. Though in near disbelief the next day, the stunt would essentially provide Hawkins with a career, exploiting the character that he unintentionally created from that point until his death. But whereas Hawkins uses brute force to voice his obsessed and possessed narrator, Nina Simone uses a different tactic entirely. Her approach is equal parts desperation and cool confidence, managing to both plead with her subject while still appearing to be in control of him. A master interpreter, it would be a mistake to look at Nina Simone as simply a jazz singer, or to tie her inherently to any other genre–her artistry transcends that kind of categorization with her ability to appropriate any material to sound only like Nina Simone. “I Put a Spell on You” is a prime example of this transformational quality that leaves the listener hypnotized beneath the affect of Simone’s voice, and it does so in only two and a half minutes.

Also released in 1965:

John Fahey – The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death (Riverboat)

Richard & Mimi Farina – Celebrations for a Grey Day (Vanguard)

Jackson C. Frank – Jackson C. Frank (Columbia)

Herbie Hancock – Maiden Voyage (Blue Note)

The Horace Silver Quintet – “Song for My Father” (Song for My Father; Blue Note)