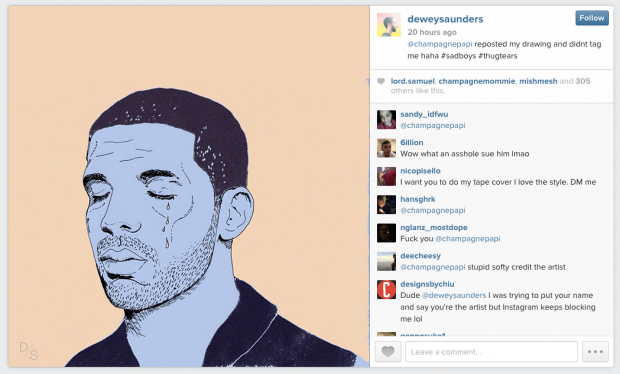

Credit Where Credit Is Due? Drake Instagrams artwork by Philly’s Dewey Saunders without attribution

In the social media universe, sharing and re-sharing is the name of the game. Someone’s creative effort can be blasted out to a whole new audience with a click of a mouse or a swipe of a finger that takes a fraction of a second.

Unfortunately, in this same universe, things like credit and attribution are handled in a bit more of a fast and loose manner – sometimes accidentally, sometimes out of laziness. Despite our best efforts, we’ve been guilty of it The Key on occasion in the past. We’ve seen it happen to the work of our contributors, too. Broadly speaking, when an artists’ work gets lifted without credit, it is often being presented to a limited audience – somebody’s personal Tumblr, for instance. Other times, it winds up before a whole universe of eyes.

The latter happened yesterday when Philly illustrator Dewey Saunders was re-grammed by rap mega-star Drake. Saunders’ work – which has appeared in a range of places from The New Yorker to album sleeves by local musicians – is bright, colorful and uniquely stylized. Of late, he has focused on Daytrotter-esque renderings of modern hip-hop luminaries from Shabazz Palaces to Kanye West.

Yesterday afternoon, he Instagrammed this illustration of Drake – who just shook up the hip-hop world with If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late, a mixtape released via iTunes. Within an hour, the illustration made its way onto Drake’s official Instagram – which boasts a staggering 7.3 million followers. Drake, however, did not credit Saunders, or tag him; he simply captioned the photo with a hi-five emoji, presumably as a means of saying thanks.

“My mom texted me saying my little brother Matt saw Drake had reposted,” Saunders tells us. “At first I was flattered, then I was pretty frustrated he didn’t tag me. It literally takes two seconds to tag someone. Kind of rude to not tag the artist. Such a small action could have changed the whole game for me!”

By the numbers, Saunders’ illustration has in a little under 24 hours racked up 282,000 likes (!) from Drake’s fans, as well as over 4,200 comments as of the time of this writing. To be fair, many of those comments are of the spammy variety (“<<<FOLLOW FOR 4 LIKES GUARANTEED!!!!!”) or the hysterical fan variety (“Marry me????????”), but still.

In the initial few hours, Saunders popped into the fray periodically asking Drake to attribute the work to him (“Tag me, G”) . He later asked his followers to “tell @champagnepapi he needs to give credit,” which resulted in additional comments attributing the work to Saunders’ instagram. This morning, Instagram user @fluride40 put it eloquently in the comments: “Drake, you’re the man bro, but it’s time to give credit where credit is due. This picture has gotten more likes than anything you’ve posted as of late. Give the man his credit. This is huge for him.” As of the time of this writing, Drake has not credited Saunders.

Musicians re-sharing the work of fans has become more and more common with the growth of visual-intensive social media such as Instagram. Whether it’s photographs of live gigs or sketches such as Saunders’, it provides content fodder for public figures who, more than ever, need to be digitally connecting with their fans on the regular.

“It cements the relationship with the fan,” says Jonathan Van Dine, drummer for Philly indie-dance four-piece Cruisr. He manages the band’s social channels, and even though Cruisr only has a fraction of Drake’s audience (about 4,400 Instagram followers), it is one enthused and engaged crowd – partly due to an explosion in the band’s fan base following a fall 2014 tour with The 1975.

When Cruisr reposts a fan’s work, however, Van Dine is diligent about crediting the creator – something that’s hard to miss in the band’s Twitter and Instagram feeds, and even on its Facebook page.

“As a photographer myself, it’s so rewarding to get credit by a band,” Van Dine says. “I believe in giving credit to anything creative.” Remember when he was talking about cementing the relationship with fans? It’s not just about providing an ongoing stream of content for fans to engage with, it’s about forging that one-on-one bond where the band directly shouts out a fan in front of their entire digital audience when they create something attention-grabbing.

However, sometimes – as with Saunders- what might narrowly be viewed as “fan art” is actually the work of a practicng commercial artist who happens to be a fan.

On a personal level, back in my freelancing days I would often see my photography turn up in other places – artist’s online profiles, other blogs – and it still happens on occasion. I’ve never been aggressive about pursuing photo credits, though. One, because I’m not a particularly aggro dude, and also because my creative work was always something on the side of a day job that paid my bills. Not everybody is in that situation, though, and for this piece I asked freelance photographers I’ve worked with to share their experience.

Rachel Del Sordo, who contributes to The Key and JUMP Philly Magazine has had her photographs show up unattributed in places from Noisey (which, to their credit, attributed a photo to her after she contacted them) to artist Instagram pages (which sometimes credit her, sometimes not).

“We – bands and photographers – are all artists trying to make a living doing what we are most passionate for,” she says. “If you find someone’s work that you love, treat it in a way that you would want someone who found your work to treat it. Taking someone’s work without permission or acknowledgment isn’t helping anyone. It’s also just rude, you know.”

Morgan Smith, who contributes to The Key and Philadelphia Weekly, has also experienced artists screengrabbing photos from her Instagram and sharing it on their own, most recently with actress / rapper Chanel West Coast performing at The Troc. “I don’t usually watermark my photos, but for some reason (thank god) I decided to watermark this particular photo before I posted it,” says Smith. “Since she just screenshotted it, my watermark was in the photo she posted, but its not the same as having a direct tag. I doubt anyone is going to go through the trouble of searching for my name from the watermark.”

Other Key contributors have similar stories. Rachel Barrish calls it “annoying but flattering”; Cameron Pollack recalls giving a musician a pass because he, too, was just starting out as an artist. Megan Kelly adds that most artists who actually ask for permission first are either smaller-profile acts and are usually local. “I can’t figure out if this is out of respect for the ‘up and coming artist’ and they understand the struggle of becoming known more than more-established bands, or if it’s a generational thing,” she says. One thing that’s certain, though – risk is inherent when you try to build your artistic profile in a digital world.

“If you have ever put something on the internet, I’m sure there’s at least 10 other sources using your stuff without your consent,” Kelly says.

Asked if the experience changed his appreciation of Drake’s music or his view on him as an artist, Saunders says “I’m thinking of him differently now, for sure. He seems pretty insensitive and unaware of the power his influence has to help upcoming artists.”

But it also doesn’t deter Saunders from from putting his work out there publicly on the internet – around the same time the fallout from Drake’s re-gramming was going down, Saunders was Tweeting illustrations of Action Bronson.

“Guys like Action Bronson always tag the artist and show love to those who do pieces of him,” Saunders says. “This same scenario [with Drake] happened when Mac Miller posted a drawing I did of him, saying ‘Shout out to whoever did this.’ He later reposted and tagged me, which was really cool and it boosted my instagram account a lot. Shouts to Mac.”