Dare to be Different: The importance of Philly’s WDRE, 20 years later

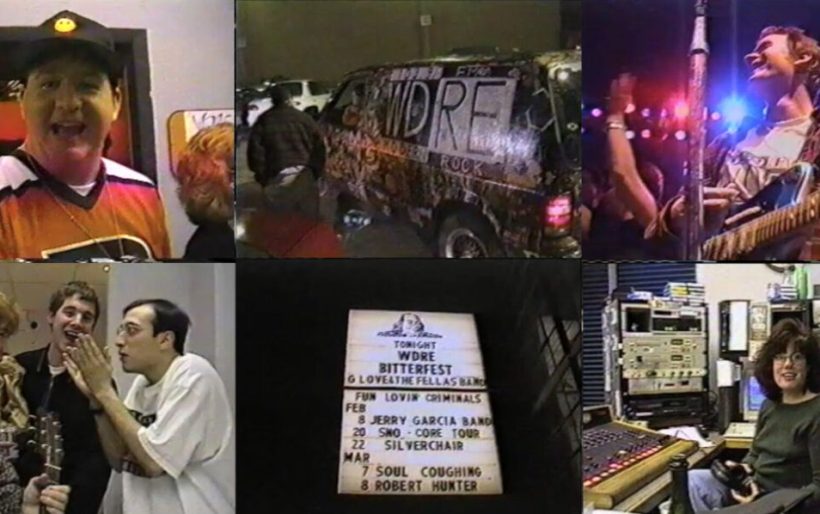

WDRE staff and fans, circa 1997 | stills from video by Andrea Corbi Fein

Preston Elliot had starry-eyed expectations as he drove to Philadelphia in 1995. He was on his way to a new gig as afternoon host at an alternative rock radio station, a format he was very excited to transition into; it was also his first radio job in a major market after several years of hosting top 40 in St. Louis. Visions of an immaculate production studio with big, shiny, state-of-the-art equipment and all the comforts of a big city kept him excited on the 18-hour trip.

And then he got to WDRE.

The station was coming out of a bumpy three years at 103.9 FM on the Philadelphia airwaves, mixing various degrees of local hosting with a simulcast from a parent station in Long Island. It had recently re-established itself with an all-local airstaff broadcasting out of a studio in a Jenkintown office park. A studio that, to put it mildly, was rough around the edges.

“I walked in, and Bret Hamilton was on the air,” remembers Elliot . “He saw the look on my face, we exchanged pleasantries. And then he said ‘Yeah, I thought the same thing when I first stepped in here as well.’ He could read my mind.”

The host microphone was held onto the stand with bumper stickers; the wall was soundproofed with blue foam. The booth was small; Elliot, who now has a much more spacious studio co-hosting the Preston & Steve morning show on WMMR, likens it to a tiny closet. In short, DRE was kind of a dump.

“But it ended up being really really fun,” Elliot remembers. “It was kitschy, it was cool, it had attitude.” And that fit perfectly with the station’s voice in the regional radio landscape. “How ratty that studio was gave us as jocks this feeling of edginess, of not being polished by any means at all.”

For the relatively short time that it was around, WDRE was a pivotal music source for young listeners across the Philadelphia region. It was the first local station entirely dedicated to the alternative rock boom — the first station to prioritize a new generation of emerging artists over leftovers from the classic rock era. It signed on the air in November 9, 1992, a simulcast with WLIR in Long Island augmented with local hosts like Mel “Toxic” Taylor and Marilyn Russell, and after a whirlwind five years, signed off on February 7, 1997 — 20 years ago today.

“It was a legitimate new music source that you could get for free,” remembers Dan Fein. “You didn’t have to buy Rolling Stone magazine, you didn’t have to have a cable subscription so you could get MTV. You could could count on DRE to get good new music and make a mix of music you couldn’t get anywhere else.”

Fein worked in DRE’s promotions department as a college student before moving on to gigs at Y100 and WMGK; the slogan in the early days was “WDRE — We DaRE to Be Different.” He was also an intern for Russell, who hosted DRE’s new and local music show on Sunday nights, as well as MCing showcases around town at places like Old City’s defunct club The Middle East. It was a tight-knit group, Russell recalls.

“I’d call the studio, driving home from a gig, and request songs from whoever was on air, telling them I need to wake up,” Russell laughs. “But I feel like we really had that connection: like-minded people, really into the same music, and not going to compromise.”

DRE was Russell’s first job in radio; she had experience doing freelance voiceover work, and climbed the ladder from answering phones in the office to acting as a drop-in music news host on the morning show, ultimately establishing her Sunday night showcase. She likes that the station continued to hold a torch for 80s artists like Depeche Mode and The Cure — artists who continued putting out stellar work in the 90s but were shunned by rock radio. She also liked that the format was female-friendly, unlike mainstream rock radio, citing Tori Amos, Alanis Morrissette, PJ Harvey, and Hole as some of her favorites.

By 1994, though, something changed — as the saying went, alternative had become mainstream, and alt-minded stations like DRE faced an identity crisis. What do we do when Pearl Jam started showing up in the mix on Y100, which was a pop station at the time, or in WYSP’s hard rock mix? The answer: go deeper. Don’t play artists that make the mainstream jump; focus on new and undiscovered. Rebrand as the Underground Network.

Turns out it wasn’t the right answer.

“What happened was a pretty big backlash,” explains Fein. “People were like, ‘what the hell is this? Why are you not playing Pearl Jam anymore? Where are all the artists I love?’ We realized you have to lead people into new music by surrounding it with familiarity.”

Enter new program director Jim McGuinn, who was brought in to Philly from KPNT in St. Louis. He’s had a storied radio career in the years since — steering the ship at Y100, then putting in several years at WXPN before relocating to Minneapolis to become program director at The Current. When he came to DRE, as he tells it, the ratings had taken a dive from a 3.1 to a 1.3; and even if you don’t understand the nuances of audience calculations and market share, that’s clearly a bad thing.

“Perhaps the Underground Network was too fast too far, either ahead of its time or there was no time under which it would’ve worked,” reasons McGuinn. But where the year of the Underground Network abandoned bands like Pearl Jam, “We sorta saw that as the core, and probably rightly so realized that Top 40 wasn’t going to stay in that lane forever. It would move onto the next hot, buzzy thing, and we would be there, hopefully, more long-term with this genre.”

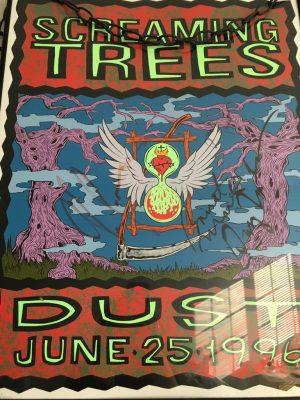

A Screaming Trees gig poster autographed at their Sonic Session | courtesy of Marilyn Russell

In his new position, McGuinn dropped the “alternative” nomenclature in favor of “modern rock,” and insisted that the station become all-local, dropping the simulcast and bringing in new hosts like Elliott in the afternoons, Bret Hamilton in middays (he had formerly been at Q102), morning show hosts Sarah Clark and Vinnie Hasson. McGuinn showed up in the mix, delivering news under the name Rumor Boy. Russell parlayed the Sonic Studio sponsorship of her Philly music nights at The Middle East into the live performance series Sonic Sessions, which showcased artists like Screaming Trees and The Afghan Whigs, Tori Amos and Weezer, played live to a room of DRE superfans.

It was a perfect storm of personalities and engagement with the listening audience that pushed the station into its golden era. The owners were still based in Long Island; there wasn’t really a general manager, and the free-spirited staff was able to experiment. “We were unafraid,” says McGuinn. “It was truly the inmates running the asylum.”

Elliot found the lack of a corporate structure both refreshing and liberating. “It was really just a ragtag group of people, and we did whatever we wanted to with Jim as our guide,” he explains. “I hadn’t been in that position before — in top 40 radio, the promo department came up with promotions, the programming department handled music. The air staff played what we were told. The way [DRE] worked, it was very communal. Everybody was invited to promo meetings, the music meetings. All you had to do was show up, all the doors were open at all times.”

Ideas were bounced around and executed, like soccer matches versus The Cure and a basketball game against PA rock heroes Live — one of the bandmates in the latter broke a finger. An ad campaign threw shade at WMMR’s “you’ve grown up, we’ve grown up” nostalgic mantra by pasting a pink toilet on a full page of the local newsweeklies, proclaiming “you’ve thrown up, we’ve thrown up.” Ridiculous contests made their way on air — like Trippin’ With Vinnie, where a lucky listener would take a road trip with the morning show’s Hasson around the country, calling in from each stop and getting goofy assignments for the day. They might spend an afternoon collecting garbage from the site of the Atlanta olympics, then getting the band Garbage to autograph it during their show in town that night. Sure, this was the era of MTV’s Road Rules, but still — a week, in a car, with complete strangers, on the station’s dime. Kinda crazy.

“We’d sit around and go ‘You know what would be cool? Let’s do it!'” recalls McGuinn. “And we just would. Because no one was paying attention to us at any level. We just had to do what we could to get attention from the audience, but also, no one was paying attention to us from a management perspective, either. So we had free reign to try whatever we thought was right in the moment.”

“It was a real winning combination of personalities and a format that was new enough and exciting enough that people connected,” recalls Russell. “We never had good ratings, but we had all the street cred in the world.”

%3Aformat(jpeg)%3Amode_rgb()%3Aquality(90)%2Fdiscogs-images%2FR-3505405-1333108685.jpeg.jpg&w=750&q=75)

DREgional Vol. 1 cover art

And that carried over to the music. The bigger artists were championed, but in a way that went deeper than the mainstream. While the pop stations were still stuck on Pearl Jam’s “Alive” (the song that famously kicked off DRE’s broadcast in 1992), McGuinn and his team were four singles deep on Vitalogy. When LA’s KROQ turned its back on Weezer as its dreary and introspective sophomore record Pinkerton was being universally panned, DRE upped its support.

“We thought it was the most amazing record, and we played like three songs from it,” says McGuinn.

“Nobody played ‘Pink Triangle,'” adds Fein. “We played ‘Pink Triangle.’ A lot.”

It was an idealistic time and, as Fein saw it, the station had a responsibility beyond ratings. “That’s important,” he admits. “We all needed to get paid. But we had this other equal responsibility and support these artists and play an important role in the community.”

Which included local support of local upstarts like The Low Road, God Lives Underwater, Holy Hand Grenade, and more — collected into the cutout bin classic DREgional Volume 1 in 1996, and anchored by the shining star of the Philly scene, G. Love and Special Sauce.

“We kind of came in on the fringe of [alternative rock],” remembers main man Garrett Dutton. “And it ended up being pretty cool because I think we ended up bringing a bit of a different flavor [to DRE], we were always a bit outside the box.”

As McGuinn reflects, “Hopefully, it gave encouragement to local bands that, here was a real commercial radio station with hundreds of thousands of listeners who could take your music and amplify it, in a way that you couldn’t from playing countless gigs at The Pontiac and The Khyber Pass.”

But, as we learned from countless episodes of Behind the Music, the party couldn’t last forever.

On January 3, 1996, President Bill Clinton signed the Telecommunications Act of 1996 — and in the process, changed commercial radio forever. The law deregulated ownership of broadcast media; with enough money, any company could own as many stations in as many markets as it wanted. It opened the gates to Wall Street and big business solidifying their foothold; it paved the way for the homogenized iHeartMedia landscape we know today. And it left independently owned mom-and-pop stations like DRE with their backs against the wall. “A lot of those owners sold,” McGuinn says, “because the money they were being offered was incredible.”

McGuinn could see the writing on the wall; he could tell that the way WDRE’s broadcast signal spanned across the Delaware Valley, it was weakest where the alternative rock audience was the strongest, in the outerlying suburbs. Demographically speaking, he knew that 103.9 would be most successful as an urban station; the notion came up when he would meet with the owners of DRE. So when the station was sold to Radio 1 and plans were announced to flip formats to a hip-hop and R&B mix, he wasn’t surprised.

“They paid roughly $5 million for DRE in 1992 and sold it for $20 million 4 years later,” McGuinn explains. “So, you couldn’t blame them as a business from the deal they made. But it hurt.”

What made the situation unique was the amount of time between the sale and the signoff: almost two months. In today’s terms, an eternity.

“It really was unprecedented,” says Russell. “You hear it all the time in radio; a new owner comes in, they make changes, everyone is showed the door. But we got to sit there and plan our own funeral party.”

McGuinn said he presented the idea of openness leading up to a farewell bash as a way to galvanize DRE fans as well as hype up the new station. “We said to [the owners], we think we could help you by helping us: by making this public instead of a mystery signoff that happens in the night. And they agreed. We got a lot of attention for that from being public and talking about the fact the station was signing off.”

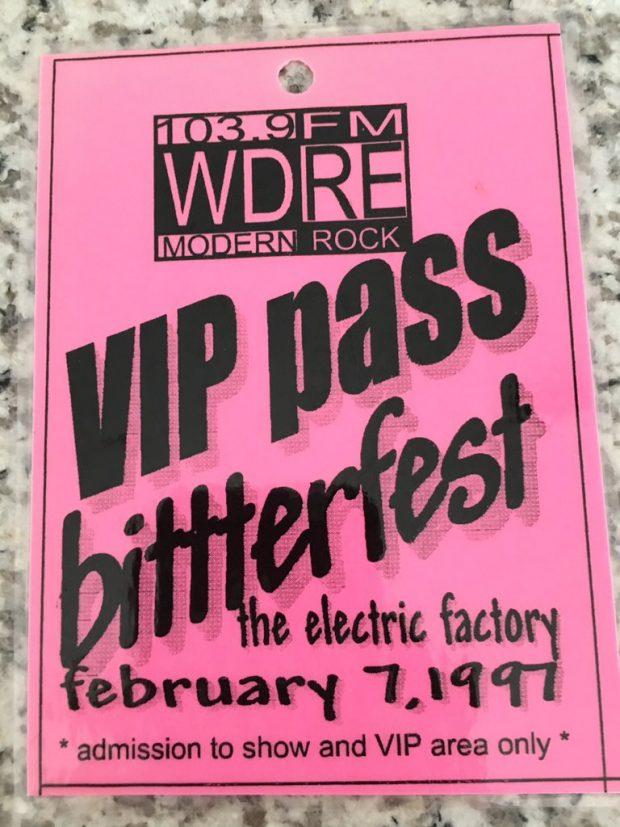

Bitterfest VIP laminate | courtesy of Marilyn Russell

It made absolute sense: it was a throwback to DREFest, the station’s big summer concert in 1996 starring Cracker, No Doubt, Fishbone and Filter, as well as locals Trip 66 and God Lives Underwater. Where DREFest took place at Camden’s waterfront amphitheater a dozen corporate owners ago (it was the Blockbuster-Sony Entertainment Center at the time), Bitterfest was set at the Electric Factory, starring Fun Lovin’ Criminals — the good time funk-hop trio that had a huge hit in “Scooby Snacks” — and G. Love himself.

“It was with the All Fellows Band, which was my high school band,” says Dutton. “In ’95 I broke up G Love and Special Sauce ‘cause we could not get along at any level….and I moved back to Philadelphia. I was really wanting to reconnect with my homies from high school. We did, and they had a loft down on Cecil B. Moore, by Temple in North Philly, and we used to jam out. So this was our first big show with that unit.”

To hype up the show, DRE’s creative hive came up with a playfully morbid run of promo spots, conceived as a group and excited by nighttime host and production director John Castino.

Spots made fun of the staff’s pending unemployment and invited listeners to “dance on our freshly-dug graves.” One imagines future careers where Hasson is working in fast food, Hamilton is disgruntled at the post office and Elliot is president of the United States after Clinton’s term is up. (He presses the doomsday button thinking it would summon a butler.)

“This is the dark humor we had, you know?” says McGuinn. “We gave away the right for someone to unplug the station at midnight. So we made out of wood, it looked like a giant plug that you would plug into the wall, it said DRE on it.”

In one clip leading up to the final days, Elliot does a rapid-fire rundown of impressions — and impressively on-point at that — of voices from every other commercial station in Philly.

“It was kind of a surreal experience,” says Fein. “It was sad to go to work every day, but we also knew we were being given this unique opportunity to throw ourselves a party.”

Dutton recalls the flash of that night at the Electric Factory on February 7, 1997 — he and his bandmates picked up custom suits for the occasion. “It was a pretty big time show for us. So we went down to 3rd and Market, where there was a suit corner called The Suit Corner. We got these very colorful, ostentatious satin red suits…and went in the shoe store next door and get matching shoes. I still have a picture of us on stage wearing these suits at the Bitterfest.”

FCC rules were tossed to the wind — f-bombs were dropped left and right. As the midnight hour approached, the audience was asked if it wanted to play music from CD, or if it wanted “to hear everybody from DRE climb behind the instruments and play a song.” The latter won out; a cover of Kiss’ “Rock and Roll” all night was jammed out.

McGuinn proclaimed “This is still fucking DRE.” (I remember freaking out about this as a teenage kid listening from home.) “Alive” was played, the plug was pulled and it was over.

“I was on the stage, the whole staff was on stage and the kids in the front few rows were chanting ‘DRE’ and crying,” remembers McGuinn. “I don’t think I’ll see anything like it in radio again; the passion that the audience had for the music that we played on the station.”

The important thing to remember here: most of this happened in the course of only a year and a half. McGuinn makes a point of saying this, not to be all nonchalant, but to put it in perspective: WDRE as a whole existed for just over four years, and WDRE’s golden era was roughly 18 months. Everybody involved has followed their career down much more fruitful and stable paths.

But from the perspective a teenager tuning in, as I was, from Montgomery County — or your perspective from Bucks, or from DelCo, or South Jersey, or wherever — those 18 months seem like an eternity. Maybe that memory is a result of the wide-eyed / wide-eared sense of discovery inherent in youth, when everything was fresh and exciting and you hadn’t yet been jaded by time and repetition and letdown after letdown.

But something about DRE felt pivotal to me, an era of supreme musical significance, an era that instilled a passion for music and discovery in an impressionable young fan that led me to discover other outlets — like college radio torchbearers like WKDU and WPRB, like the expert curators at Okayplayer and NPR Music, and like the wonderful station I now call home, WXPN.

But DRE wasn’t just pivotal for listeners.

“It was a family, man,” enthuses Dutton as we drove to the G. Love and Special Sauce show at the Electric Factory earlier this month. “We were all family, they were so supportive of us through thick and thin. To this day! I know I’ll see Marilyn Russell tonight, I know I just saw Jim McGuinn in Minneapolis. We just hung out a the state fair and had some French fries this summer.”

Elliot says his time at DRE had a huge impact. “I never worked at a radio station that was more heart than anything, like that station was,” he says. “It was a year and a half, but it was a really concentrated year and a half of fun and creativity and ingenuity. I think what made it so impactful was how crazy loyal the fans were to that radio station. If you you loved it, it was your favorite station – period. That’s the vibe I got from the DRE hardcore listeners, which made it immensely fun for us.”

McGuinn likens the free spirit of running a modern rock station in the 90s to the early rock era of the mid-60s, or the birth of punk in the late 70s.

“Nothing was codified, the cement was still wet and you were able to shape it,” he says. “It was super exciting. And I think today, you’ve both got the weight of history on alternative radio and also a much more formulaic and corporatized playing field. You don’t have as many maverick ownership groups like both Y100 and DRE had, single owners, people down the hall rather than corporations. Also, I think it was a time that was more welcoming to idealism in radio…you felt like the rules were being made as you went along.”

As Russell sums it up: it was a magic era. “It was most special time of my radio career,” she says. “Without a doubt.”

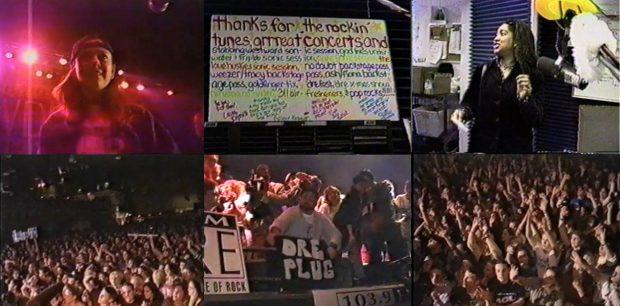

WDRE staff and fans, circa 1997 | stills from video by Andrea Corbi Fein

In addition to the people interviewed in this story, major thanks are due to Andrea Corbi Fein for sharing footage she shot at Bitterfest for her first editing project as a student at Art Institute of Philadelphia — VHS to VHS cuts and asskicking megamix, y’all! She’s since been a professional filmmaker for 18+ years. Thanks also to Joey Odorisio for his encyclopedic knowledge of all things Philly radio and fact-checking assistance. #wdre4eva