Perseverance, Pride, and Percussion: Remembering the incredible life of Elaine Hoffman Watts

Elaine Hoffman Watts drums at a Curtis Institute of Music holiday party in 1951 | photo courtesy of Mark Rubin

When Elaine Hoffman Watts passed away last month at the age of 85, the celebrated percussionist left behind an exceptionally multifaceted legacy, both in terms of the music she played and her own personal history. Raised in Southwest Philadelphia, Hoffman Watts was klezmer royalty, the next generation in a family whose musical history stretches back to before they arrived in the country from Ukraine. Her father, Jacob Hoffman, was a noted xylophone player and percussionist who was a fixture in Philadelphia music for decades, especially when it came to the klezmer bands that would play at weddings and other occasions in the local Jewish community. It was under his tutelage that she originally learned how to play the drums in the basement of their house at 63rd and Ludlow.

Hoffman Watts quickly became a formidable drummer. She was so talented that she was accepted to the Curtis Institute of Music, the first woman allowed into the the percussion department there. When she graduated in 1954 she was soon hired as a timpanist in the New Orleans Symphony. That was the first of countless jobs in orchestras, jazz groups – including sitting in for Duke Ellington and Count Basie! – and many other bands. While she’d occasionally get to play with her father’s band, klezmer gigs were incredibly rare, despite her family history and obvious talents. That’s because the genre was almost entirely closed off to women playing instruments and nobody would give her the time of day.

Fast forward to the early 90s, and the klezmer revival. Hoffman Watts was, in a way, rediscovered by Yiddish scholars and music fans, despite the fact that she had always been there. With the renewed interest came the opportunity to finally play the music she had been raised with, the music of her family. She was in bands with her daughter Susan Lankin-Watts and attended klezmer conventions around the country and in Canada. She was awarded a Pew Fellowship in the Arts in 2000, a National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellowship in 2007, and a Leeway Foundation award that same year, amongst other countless honors.

Hoffman Watts’ other musical passion – and source of income when she was not performing – was teaching. She took on thousands upon thousands of students over the decades, both at home and in a number of schools around the region. By all accounts she was an excellent and rather no-nonsense teacher. Julius Masri, who plays drums in a variety of jazz, experimental, and metal bands in Philly, was one of Hoffman Watts’ students when he was in high school. One of his favorite memories of the time was when he first met her. As he wrote in his remembrances online: “Sixteen year old me trying to play swing in jazz class only to be unceremoniously shoved off the drum throne with a ‘Lemme show you how it’s done!’” Masri said he learned a lot from Hoffman Watts and still plays the drum kit he bought from her two decades ago, something she always made sure to remind him was an excellent deal. According to everyone who knew her, she was as wry as she was hilarious, and most of all consummate in her craft — she was buried with her drumsticks.

The Key spoke wth a number of people who knew Hoffman Watts to get a better understanding of her impact on music and culture, including her daughter Susan Lankin-Watts and husband Ernie Watts; collaborator and klezmer trombonist Dan Blacksberg; Gina Renzi and Daniel Flaumenhaft from The Rotunda and Crossroads respectively, both venues she played on numerous occasions; and Debora Kodish from the Philadelphia Folklore Project, which put together a documentary about her in 2009 called Eatala: A Life in Klezmer, her nickname in Yiddish.

Dan Blacksberg

“You have to remember, Elaine is an old school West Philly person. She grew up at 63rd and Ludlow. She had deep roots here.”

West Philadelphia’s Dan Blacksberg was a frequent collaborator with Elaine Hoffman Watts and her daughter. He was 19 years old and very much just dipping his toes in the genre when he first met them at KlezKamp at the Cherry Hill Hilton in 2002. “Just one semester into college [and it was like] the roof blew off,” he said. “You’re in this giant hotel: klezmer is still pretty popular then so there’s probably four or five hundred people at this program. Music is happening constantly.”

He recalls a lesson with Susan Lankin-Watts at the camp the next year in the Catskills that had to be moved to the hotel room she was sharing with her mom due to a scheduling conflict: “So I come up and Elaine answers the door in her bathrobe and goes, ‘What?!’ I remember going inside and having the lesson and I don’t remember her [changing] at any point. She just didn’t give a fuck.”

When Blacksberg was in high school, he’d join other trombonists at the home of the late Glenn Dodson – former principal trombonist of the Philadelphia Orchestra – for regular concerts. He found out that Dodson and Hoffman Watts had gone on a couple dates back in the 50s and, “I asked her what the deal was and she said, ‘All those guys, they thought I was going to get married to them and stop playing music and raise their kids for them and I told them to fuck off.’ Imagine, it’s 1950 and she’s, like, ‘Fuck you.’”

So much of that joyfully flippant attitude could be heard in her music. According to Blacksberg, “Just nobody plays that beat like her. I think it’s a combination of the family thing and the deep percussion technique. If you watch a video [of her playing], she was tiny. A tiny person. She beat the shit out of the drum set, she was not a quiet drummer. There’s something that’s just such a powerful pushback to all the bullshit about how ‘girls don’t play drums’ or should be dainty musicians or something. She’s an old-school Philadelphian! It’s not a very subtle culture.”

Elaine Hoffman Watts drums as Dan Blacksberg plays trombone | photo courtesy of Dan Blacksberg

Blacksberg played in bands with Elaine and Susan occasionally over the past seven years. He told The Key he felt that by that point Hoffman Watts had been “lifted up as an elder” by the klezmer community, very much one of the few female non-vocalists in the genre to be recognized in this way. “I know that I just really felt amazing when we played together, it always felt really great,” he said. “One thing that was really cool was that I feel that she actually got better and was playing really some of her best in the time that I knew her.”

Because klezmer is by nature connected to Judaism and Jewish culture – though obviously you don’t need to be Jewish to play it – there are aspects of the music that change depending on where you’re from, who taught you how to play, and so on. Blacksberg, who is also the musician-in-residence at Kol Tzedek Synagogue in West Philly, referred to the social context of klezmer when explaining Hoffman Watts’ “casual” relationship with the music and culture:

“For her, I think it’s about family and connecting with her family and past. She was a member of a synagogue, lived in a Jewish suburb, raised her kids Jewish. And it’s almost like this is a separate thing than all the kinds of Judaism that we think about: Judaism as a religion, being Jewish as something you enact, or any of that stuff. And they did all that. But opposed to some of the people in New York [klezmer circles] where maybe they grew up in the socialist bund [ed. note: secular Jewish labor movement] and went to all the socialist summer camps and had this huge theory and formula about what they did – this is just a family that played klezmer music really well.”

If there was one theme in Hoffman Watts’ life that comes up again and again, it’s perseverance. She had this fantastic career as a musician and percussion teacher starting in the 1950s – very much an anomaly for a woman, much less a Jewish one – and did it all while helping raise three kids. As Blacksberg explained, “You don’t hear about these heroic victories in her story. You just hear that it was hard and she did it. It’s kind of amazing. And like I said, there’s something powerful about this tiny lady just beating the shit out of a drum set.”

As far as her legacy goes, “She should get all the credit for having a killer groove and people should figure out how to play like that,” Blacksberg said. He hopes more people become interested in klezmer drumming, especially women. He plans on keeping her memory alive in the most appropriate way: through music. “The music and the repertoire is going to get carried on by her daughter and me and the other people who were close to her,” he told The Key. “All of us.”

Susan Lankin-Watts and Ernie Watts

“She was still teaching. She went into the hospital and I had to cancel two students.”

Susan Lankin-Watts was by her mom’s side regularly over the past two decades, oftentimes quite literally so when they were on stage together as part of bands like KlezMs., and The Fabulous Shpielkes, with Elaine on drums and Susan playing trumpet or singing. “Performing and teaching were her things,” she explained. “She didn’t stand for women’s rights, she wasn’t political about it. She wasn’t anything but living how she wanted to live. This is what she wanted to do, this is how she wanted to do it, she lived life on her terms, and it didn’t matter that she was a woman. She didn’t care. And her father didn’t care either.”

Even so, many did care that Hoffman Watts was a woman and that’s something that very much kept her from playing in klezmer bands until much later in life. Asked if her mom was bitter about that, Lankin-Watts said, “Yes! She hated it. She hated it. Absolutely hated it. Misogynistic shit.”

She was better received as a professional classical musician, Watts explained. “The classical music world which she worked in up until 20 years ago – and was first call in Philadelphia for all the shows – that was her work. That’s what she did,” she said. “And they accepted a woman, they accepted a Jew. That’s another impact that I’ve been thinking about lately is the fact that she was a Jewish woman doing all this.”

Hoffman Watts’ Jewish identity was an incredibly important part of who she was, her daughter said. That was reflected not just in the music she played but also in how she lived her life and especially in how she raised her children: “We all went to Hebrew school. She drove in the Hebrew school carpool. We all got mitzvah’d. And every Friday night, she would throw a dish towel on her head and light the shabbos candles and say the brochas.”

Elaine Hoffman Watts drums at her wedding | photo courtesy of Mark Rubin

Ernie and Elaine Watts were married in 1955. “I was her roadie for 62 years,” he proudly exclaimed. He was witness to everything she went through and had an infinite number of stories about her performances, like when she played with Count Basie or when she filled in for her dad for a performance of The Man of La Mancha with José Ferrer. According to him, “Her father was the drummer for the band. The day before the show opened, he got sick, rushed to the hospital. No drummer. They asked him, ‘We need a drummer, can you recommend anybody?’ He said, ‘Yes, my daughter.’ She read the score through with the conductor the day before she opened. And when the show opened nobody knew the difference. She was a musician, not just a drummer.”

That attitude was also present in her teaching. He told The Key about a student who asked Hoffman Watts to teach him how to play rock music and that her response was, “’I don’t teach rock. I teach the drums. You just have to go find somebody else if you just want to play rock.’ And that was it.” Many of her students went on to careers in music, including Gerry Brown, who was Stevie Wonder’s drummer for years, and Steven Wolf, who has played with everyone from Grover Washington Jr. to Katy Perry and countless others.

“She required her students to know how to read music. She said you had to know how to count, you had to know the rudiments. That’s how she taught,” Ernie Watts explained. “She didn’t rush and she didn’t say, ‘Half hour is up, goodbye.’ If they were doing something in the middle she kept them until they were finished.”

Hoffman Watts was honored many times over her lifetime, including a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship award in 2007. Lankin-Watts said that the award ceremony and concert was one of her favorite memories of her mom. She also shared a far earlier story of a time when she was about 13 years old and Hoffman Watts took her along to play at a dance at a mental hospital in the Philadelphia area. This was a ‘green sheet gig’ as part of the local musicians’ union, a way for union members to get a guaranteed number of concerts each year. Hoffman Watts would bring her daughter along to give her more experience playing the trumpet.

“I learned how to be a musician from early on, she took me on all her gigs,” she said. “Had to play my trumpet with all these amazing guys.” The dance at the mental hospital was held in a space that she described as “a dark room with a disco ball” full of heavily-medicated patients. She said that the juxtaposition between the environment and the fact that, “here we were playing ‘Satin Doll’” was completely absurd.

But even if it wasn’t always the most traditional,Lankin-Watts valued her upbringing greatly. She always looked up to her mom and not just as a musician. Asked about her legacy, she said: “I don’t know how history is going to look at my mom. It’s too soon. I know that for me she is a role model for women who want to work, have careers, have children, have a family, and do everything.”

Debora Kodish

“She didn’t have it easy, a woman, a Jew, from an immigrant family, a working class kid. The first. Always the first.”

Debora Kodish is the founder and former longtime director of the Philadelphia Folklore Project, a West Philadelphia-based “independent public folklife agency that documents, supports, and presents Philadelphia-area folk arts and culture – including the arts of people who have been here generations and those who have just arrived” according to their website. The Folklore Project worked on a number of projects with Elaine and Susan Watts over the years, including concerts and two documentaries: Eatala: A Life in Klezmer — watch that full doc here — and Goodnight Mishegas — watch that short doc here.

“It was important to me that Elaine get the recognition that she deserved: as a woman, a traditional artist, and someone who was a remarkable (and unassuming) change agent,” Kodish told The Key in an e-mail. Hoffman Watts was “fluent and skilled in many musical languages,” she said, and that allowed her to move between styles and genres easily.

Kodish said that Hoffman Watts “had a tremendous impact” on klezmer traditions, both as a performer and a teacher: “And this despite the fact that the Jewish men in Philadelphia who were bandleaders wouldn’t hire her ‘because I was a girl,’ she said. Of course, she played in her father’s gigs (and at her own wedding!)”

Big Huge Yiddish Klezmer Dance Party at the Rotunda in West Philly on December 20, 2015 | photo courtesy of Alan Lankin

She described Hoffman Watts as a “consummate musician” who was always busy playing around the city. “She knew a huge number of musicians in Philly and was the first person a number of people would call when they had to put together a band for a job,” Kodish said. “People who worked with her loved her!”

Hoffman Watts was part of many different musical scenes in Philly and that was very much due to her family and educational background. Even if she was mostly kept from playing klezmer until much later, she was able to use what she learned from her father growing up to go to Curtis and become an orchestra-level timpanist. Kodish explained how, “She didn’t have it easy: a woman, a Jew, from an immigrant family, a working class kid. The first. Always the first.” Not only was Hoffman Watts breaking boundaries in music but, “She was a working mom before it was common, and she had a family and full life,” Kodish added.

What some might call being thickheaded, Kodish characterized as “the importance of persistence, of doing what you love with people you love, of being who you are.” From a folklorist standpoint, what Hoffman Watts was doing with her music was, “tracing roots and carrying forward collective traditions: peoples’ sounds, agency, love, spirit: core elements that make us human,” according to Kodish. The Eatala documentary that she helped make exemplifies this aspect of Hoffman Watts perfectly.

So much of the values that described Hoffman Watts were a reflection of the klezmer that was at her roots, Kodish said. That culture, going back hundreds of years, was based in, “being a decent person, a mentsch, and valuing mishpocha [family],” she explained. “She took such joy in her family, past and present. She was so proud of everyone.”

Gina Renzi and Daniel Flaumenhaft

“I think her impact on music, especially in Philadelphia, cannot be overstated. I can’t imagine how much she knew, how many traditions she lived and breathed.”

Making live music requires a performer and audience, obviously, but you also need a space for everything to happen and someone to promote and publicize the show. The final people we spoke with to get their memories of Elaine Hoffman Watts are Gina Renzi, Director of The Rotunda, and Daniel Flaumenhaft, Director of Crossroads Music, two places she played often in Philadelphia.

The most recent show Hoffman Watts and her daughter played at The Rotunda was last year at the Big Huge Yiddish Dance Party, a semi-regular series that serves as both concert and community get together. Organized by Dan Blacksberg, the party would pack the place with klezmer fans young and old from around the region.

“All of the shows were extremely warm and welcoming, like a family reunion with music that brought me back to the old country – someone’s old country somewhere,” Renzi told The Key. “There was always lots of food, dancing, hugs from old and new friends, and a genuinely open vibe that isn’t present at all public events.”

That friendliness was something that emanated from Hoffman Watts, too. Flaumenhaft told the story about how she made him accept a ride home from an event at the Folklore Project one year despite the fact that he lived just a couple blocks away. According to him, “When you met her offstage she was very in the role of stereotypical Jewish grandma. Very warm but at the same time very down-to-earth and no-nonsense. But then when she was on the stage and behind the drums she rocked out. The two together made complete sense.”

Elaine Hoffman Watts plays Xylophone with Fabulous Shpielkes at World Cafe Live in 2008 | photo courtesy of Alan Lankin

That was something Renzi also saw. “She meant business on the drums, she was serious about her role in the bands, she was funny, she was gracious, she looked like my Nana, and her Philly accent was much like my own – it sounded like home to me,” she said. “What more could anyone want to be in life? Totally kick ass.”

The first show Hoffman Watts played at Crossroads was with all-women klezmer band KlezMs., which included Susan Lankin-Watts on trumpet, trombonist Rachel Lemisch, and Katt Flagg on accordion. This was in 2002, during Crossroads’ inaugural season.

According to Flaumenhaft, Hoffman Watts was not just a bridge to an older generation of klezmer musicians but also in many ways a keystone in the current scene, especially in her role as teacher. He told The Key that, “…even people who didn’t directly take lessons from Elaine – she was around and they knew her.” To occupy both these types of spaces was highly unique and very much contributed to her fueling the feeling of continuity present in klezmer.

Renzi said that watching Hoffman Watts on the drums was awe-inspiring. “It was obvious that she had spent decades at the drums; she commanded them and made it look effortless,” she said. While she might have been shut out from playing in klezmer bands until she was much older, Hoffman Watts managed to cram a lifetime’s worth of music into the last twenty years.

“I can’t imagine how much sexism and misogyny she experienced as klezmer bands turned her down left and right. But I like to think that she greeted it all with grit and her impish smile, because she knew how special she was, and what deep roots she had,” Renzi said. “In other words, she must have known that she would be okay and that the music would never stop.”

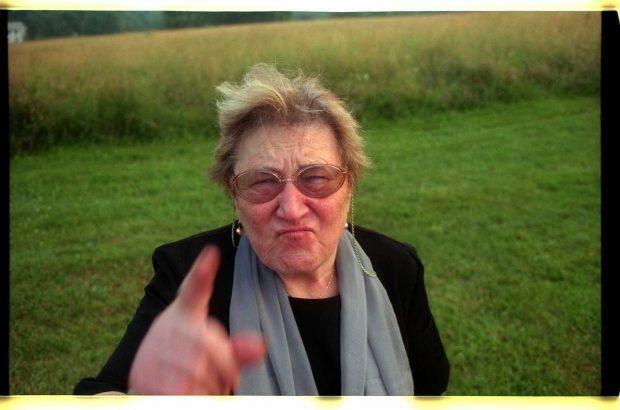

Elaine Hoffman Watts | photo courtesy of Josh Dolgin