From the Uptown to The Spectrum, take a musical tour of Broad Street

The Spectrum in South Philadelphia, circa 1969 | photo by Michael J. Maicher | courtesy of the Temple University Urban Archives | digital.library.temple.edu

There’s a joke from comedian W.C. Fields that goes like this: “First prize was a week in Philadelphia. Second prize was two weeks.” Fields, who was born in the suburbs of our beloved city in the 1880s, knew its reputation for entertainment was, at the time, laughable. If you were a person in his audience, a person who paid money to be entertained, Philadelphia just wasn’t your bag. Even today, it’s likely you’ve had a conversation with an out-of-town friend that started or ended with them asking, “What’s there to do in Philly, anyway?”

We know there’s a lot. Specifically in music, with the come up of large venues like Union Transfer and The Fillmore, we’re getting less slack for being a flatline between New York and D.C. or Baltimore. Still, despite our scene — rich to us right now — we’re kind of destined to forget the scene that came before us, or the one before that. It’s not our fault, it’s that these historic, exciting, tragic, romantic, piss-stained buildings, banquet halls and flophouses eventually close down. They disappear, and when they do, there’s no one really touting their memory.

Following the recent buzz around 858 N. Broad, a hulking figure in North Philly that was built in 1908 as The Metropolitan Opera House and recently purchased by Divine Lorraine developer Eric Blumenfeld for future renovation, we decided to play a game of Broad street memory lane. Read about some of the special places lodged in the history of the 14th Street music scene below.

The Spectrum in 1981 | photo courtesy of the Temple University Urban Archives | digital.library.temple.edu

The Spectrum

3601 S. Broad Street

The indoor sports arena opened on South Broad in 1967. It’s first non-sports event, the Quaker City Jazz Festival, was put on that same year by Larry Magid, Philly music legend that responsible for the Electric Factory and helping to bring Live Aid 1985 to our locale, among other things. After that initial show, everyone from Elvis, Pink Floyd, N.W.A., Queen and Whitney Houston performed at this musical epicenter. It was demolished in 2010.

Three M’s at the Uptown Theater | via Philly Jazz Blog

Uptown Theatre

2240 N. Broad Street

Older in years and arguably more rich in history, this was Philly’s most prominent venue of The Chitlin’ Circuit — which served as a road map of entertainment venues throughout the East, South and upper Midwest that were deemed safe for black artists to perform at during racial segregation. Built in 1929, the venue was re-popularized between the ‘50s and late ‘70s, when radio personality Georgie Woods booked artists like The Supremes, Ray Charles, Sam Cooke and The Jackson 5. Woods played a pivotal part in Dick Clark’s American Bandstand (originally filmed on location at 45th and Market), serving as his advisor for up-and-coming talent coming out of the black community. Woods turned Clark on to acts like The Temptations, Stevie Wonder and Michael Jackson. In 2004, he was inducted into The Broadcast Pioneers of Philadelphia Hall of Fame for his leadership in radio, music and the Civil Rights movement. Today, the Uptown stands on a stretch of North Broad off of the Susquehanna-Dauphin subway stop, a stark memory of what it once was with only its marquee and broken bulbs spelling out U P T O W N to mark its legacy. That stretch of Broad between Diamond and York streets was renamed ‘Georgie Woods Boulevard’ after his death in 2005.

A flyer for Crash Course in Science at Love | via Facebook

The Love Club

Broad & South

There was a pulsing radius around South street that has since fizzled out, but it once served as a hotbed for jazz, punk, rock, hardcore and glam for generations. With a little Internet digging you’ll come across “The Love Club, Philadelphia”: a Facebook forum rife with memories of broken bones, police intervention, and drunken makeout missed connections. Once one of the most notable DIY punk spaces of the ‘80s, The Love Club — also referred to as “Love Hall” — held shows by the Dead Milkmen, Black Flag, Minor Threat, Bad Brains and Husker Du, to name a few. Dead Milkmen lead singer Rodney Anonymous had this to say about the space: “I had more fun OUTSIDE of the venue, watching punks shout ‘It’s 1983, not 1977!’ at other punks who were wearing Ramones t-shirts. It was outside of the Love Club were Ian MacKaye was run over by a taxi and then taken to a hospital where he allegedly refused pain medication because he was straight edge,” Rodney remembers. “This cemented my opinion that there’s something seriously wrong with that guy.” (UPDATE: Though Minor Threat did play Love Hall, we believe that Rodney might be partially confusing it with Buff Hall in Camden, where MacKaye was injured when his band’s van was struck by a car; he went to the hospital, then returned to play the show.)

Pep’s Musical Bar | via Hidden City Philadelphia

Pep’s Musical Bar

Broad & South

Many great jazz, soul and R&B artists took part in Pep’s ‘live sessions,’ including saxophonist and flutist Yusef Lateef, whose summer of 1964 show at the South Philly establishment lives forever on vinyl. Nina Simone and The John Coltrane Quartet also left their mark on Broad and South. In a moving excerpt from Anquinetta V. Calhoun’s novel, Chasing Coltrane, she writes: “In June of 1965 the John Coltrane Quartet plays at Pep’s for one week to a full house. Coltrane’s personal life is falling apart and he has put his sorrows into his version of ‘The Last Blues.’ Tyner sits out this one while Trane and Elvin duel. I can hear them. Elvin is louder than a barreling freight train and Trane is making the tenor scream, but it’s a blues and sometimes crying is loud.”

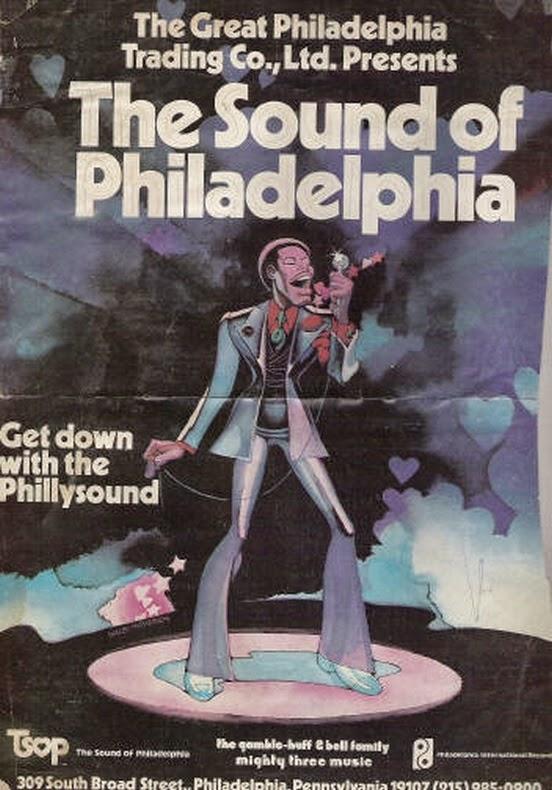

Vintage poster celebrating the House of Hits | via Souls of Black Notes

The House of Hits

309 S. Broad Street

This building was home to Philadelphia International Records, stomping ground for Leon Huff and Kenneth Gamble, Philly’s first “constant hitmakers.” The legendary ‘70s songwriting duo whose productions for artists like The O’Jays, Teddy Pendergrass and Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes struck the first chords of what’s now referred to as “Philadelphia Soul” or “The Philadelphia Sound”. It was in this relatively obscure red brick box of a building that the signature regional R&B/soul mashup was founded, consistently churned out and turned to legacy. Prior to Gamble and Huff was Cameo-Parkway Records, for which Chubby Checker recorded his hit cover of “The Twist.” Then, in 2010, arson started by a drunk South Philadelphia man essentially destroyed the structure. Reportedly, the man stumbled into a third floor closet full of memorabilia and tried to use the flame of his lighter to find his way out, literally sparking tragedy. The building was torn down in 2015, with rumored plans for high-rise apartments come this year. According to Philly Voice, “In honor of the building’s history, signed gold bricks will be placed in the new hotel’s foundation.”

Douglas Hotel | via Philly Jazz Blog

*Honorable Mention*

Douglass Hotel

1409 Lombard

The Douglass Hotel is not technically on Broad Street, it’s a stone’s throw away, but we had to call this one out for its decades of cultural importance. It’s fun to walk by this stark white building today — past the plaque claiming that Billie Holiday “often lived here” — and wonder what you might have seen if you took your stroll a few decades early. Douglass Hotel, a South Philly institution for black entertainers and visitors through the ‘20s and ‘50s, served the clientele that the segregated Center City hotels did not. That said, it was a hotbed for talent. In 1964, the Douglass opened its basement as The Showboat, a venue with room for about 200 guests to watch performances by Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane and Aretha Franklin. Nearly a decade later the same space was renamed The Bijou Cafe, hosting then up-and-coming artists and entertainers like U2, Prince, Tom Waits, Jonathan Richman and Jerry Seinfeld. A local band called Whole Oates opened the Bijou’s first show in 1972. They later went on to play many much larger venues as Hall & Oates. For a taste of what the space sounded like, listen below for a magical 1963 live recording of John Coltrane at The Showboat.