Taylor Mac’s 20th century: Twelve hours of song and struggle, solidarity and sex

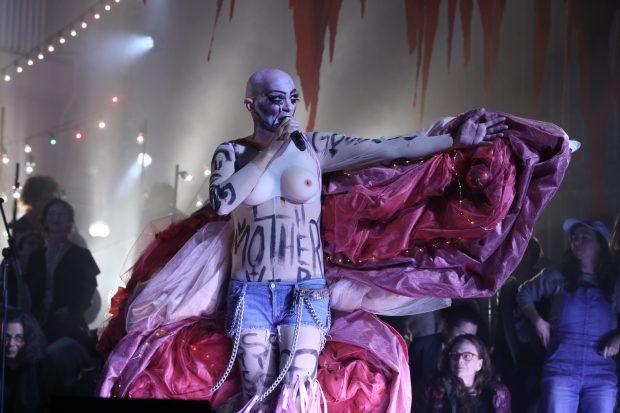

Taylor Mac | photo courtesy of the artist

As I entered the Merriam Theater on Saturday, June 9th, as the PIFA street festival was slowly whirring into life outside on South Broad street, I braced myself. What I was about to experience, whatever it turned out to be, was definitely going to be way too much. How could it possibly not be? We’re talking about a non-stop, twelve hour long performance; an epic history-inspired drag cabaret-as-endurance feat, featuring upwards of one hundred songs – roughly ten per hour, or per decade since the starting point of 1896. Actually, this was only the second half of what is, in full, a twenty-four hour work, the first twelve hours of which – covering the decades between 1776-1896 – were staged a week prior. (It’s been presented as an uninterrupted 24-hour marathon only once – in Brooklyn two years ago – but the Philadelphia iteration notches a solid runner-up in the insanity stakes.) Still, much too much seemed like a foregone conclusion.

Here’s the funny thing though: it really wasn’t. Not everything in the twelve hours worked, of course, but an astonishing amount of it did. I was engaged more or less instantly – for one thing, I was called onstage twice within the first two hours (first as part of a wave of immigration from “Eastern Europe” – a.k.a. the back of the house – to an increasingly crowded turn-of-the-century “Jewish tenement” represented by the stage; second, along with every other male in the audience between 14 and 40, as a WWI conscriptee.) And I was never bored. I was never turned off, or overwhelmed in an unfavorable way. I only left the auditorium twice, for no more than two minutes (it was all I could bear.) And when I left for good, shortly after midnight, I was fully satisfied and yet still ready for more.

The show, A 24-Decade History of Popular Music, is not just a cabaret performance; not merely a concert, but (also) a costume spectacular, a psycho-political identity-poetics deep-dive, an audience-participatory historical re-enactment and re-calibration, a rip-roaring communal performance art party. Or, as described by its mastermind, master of ceremonies, constantly captivating central figure and the singer of all but a handful of those seemingly-innumerable songs – one Taylor Mac – it is a “radical faerie realness ritual…sacrifice.”

Taylor Mac | photo courtesy of the artist

Taylor Mac | photo courtesy of the artist

Mac is a multi-talented theater artist and 2017 MacArthur “genius” whose adorable and preposterous choice of personal pronoun (with an emphasis on persona), which I’m almost perversely delighted to employ, is judy. judy’s gender is “performer,” and that feels precisely accurate. As distinct from your standard, run-of-the-mill drag queen, and despite gender and queerness constituting the show’s most prominent through-line, judy didn’t really perform gender so much as transcend it: trans-gender in the sense of “beyond”, rather than “across.” And that was only accentuated by the stunningly intricate, wonderfully fanciful, over-the-top, convention-exploding wearable art installations – a new look for every decade – created by the very aptly named designer Machine Dazzle, who often came onstage (looking equally fabulous) to adorn Mac personally. Camp is one element in judy’s performative toolbag, to be sure, but so are wit, empathy, earnest sentiment, nuanced musicality, political conviction, history-geek enthusiasm, erudition (despite the “popular” in the show’s title, the highbrow arena got its due as well, as with a reading of the magnificent final pages of Ulysses) and, especially toward the later parts of the show, candidly intimate personal anecdotes.

There was precisely one moment when I turned to a friend and said “now, this seems just a little indulgent.” But it wasn’t the astoundingly acrobatic, by-no-means-simulated “prison shower scene sex fantasy” orgy that took place onstage during the 1946-’56 “suburbanization” decade. Nor was it the pair of gigantic inflatable cocks – one adorned with the Stars and Stripes; the other Soviet red with a hammer and sickle – that lumbered above the audience before clashing orgasmically, to the epic strains of Bowie’s “‘Heroes,’” as the climax of the 1976-’86 “decade of the backroom sex party” (and, evidently, of the cold war.) No…that felt totally earned. It was what happened just after that: Mac performed “Purple Rain” – introducing it as “the best make-out song ever” – which somehow struck me as the first disappointingly obvious selection; the second mega-iconic anthem in a row, and a surefire crowd-pleaser but, in context, not much more than that. (Perhaps if it had inspired more than a bit of mild face-sucking from a handful of audience couples.) Then again, if there’s ever an appropriate moment to be lavishly excessive with your lavish excess, the 1980s is probably the time to do it. So maybe that was right on the money too.

Taylor Mac | photo courtesy of the artist

There’s so much to be said about the show, from so many angles: as an emotional and spiritual (and physical) personal experience; as an agenda-driven socio-political project; as a metaphor for any number of things. Mac’s synopsis of its overarching theme is: “How do we [i.e. members of a marginalized community or subculture] build ourselves because we’re being torn apart?” (The punchline: “I don’t have the answer, I just ask the question for twenty-four hours!”) But this being a music blog and me being a noted song expert and all, I’ll try to focus on the show’s musical aspects.

One note on the title: it’s called a history of popular music, but it’s at least as accurate to say it’s a history through popular music. Mac – whose musical/historical/social/personal commentary and analysis constituted a substantial portion of the show – was typically less interested in the songs themselves than what they taught us about their respective eras. Indeed, one of the main reasons I wish I had seen Part I the previous week (I was busy running/performing in West Philly Porchfest, and then enjoying a surprise free ticket to the Justin Timberlake concert…but even so) is that I imagine the 1776-1896 period provided a richer opportunity to weave in musicology and music history: the songs are more likely to be either totally unfamiliar or so familiar (the very first decade opens with “Amazing Grace,” and features “Yankee Doodle” as a kind of keynote) that they beg for contextualization – and can reveal that much more about a bygone and mysterious time period. We got a whiff of that at the beginning of Part II, but by mid-20th century the dynamic had shifted considerably, as both the songs and their historical contexts were now largely familiar. (In the show’s last few decades, as I’ll describe, the parameters of the game began to change altogether.)

Taylor Mac | photo courtesy of the artist

Actually, the 1890s – and immigrant New York in particular – is probably as good a point as any to start a history of “popular music” as we tend to think of it. Mac didn’t say the words “Tin Pan Alley,” but the first decade was set up as an exploration of the ethnic, subcultural roots of that soon-to-be-dominant mainstream force, as Mac alternated between old-world Yiddish tunes (some of them translated especially for the show) and the likes of Irving Berlin’s “All Alone” (an ironic conceit, as judy delighted in pointed out, for a song by a tenement-dweller) and “Everybody’s Doin’ It” (a song with a strong Philly-theater resonance for me, as it was used as a leitmotif in Pig Iron’s Gentlemen Volunteers – and which I think of every time I hear the Mr. Softee jingle.) Mac also gave us a tidbit of social history via song here, explaining how the lack of indoor privacy in crowded tenements inspired odes to open-air courtship like “Shine On, Harvest Moon” and its close relative “By The Light of the Silvery Moon” (for the latter, exhibitionistic audience members were invited up to moon the crowd on every repetition of the word “moon.”) This decade also included “Happy Birthday to You” (no major revelations – though I just learned that it’s finally, officially in the public domain) and “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” which prompted a “queer” baseball game featuring the day’s first nudity and by no means its last.

The World War I decade – kicked off by a standoff between the pacifist “I Didn’t Raise My Boy To Be a Soldier” and its hawkish co-optation/parody “It’s Time For Every Boy To Be a Soldier” – made intriguing symbolic use of folk and blues tunes (“Make Me A Pallet On the Floor,” “O Death,” “Danny Boy”) rather than what we might think of as the era’s “popular” music. Mac did, however, make a not-terribly-convincing case for Ivor Novello’s “Keep the Home Fires Burning” as proto-feminist, positing it as an anthem for what you might call “lesbians until armistice.” The Roaring Twenties sequence was framed as an examination of the tension between two polarized reactions to the war’s horrific death toll: post-traumatic numbness and denial-fueled frivolity. Ushered in with the deliberately wearying forced-gaiety of “Happy Days Are Here Again” (complete with a conga line and innumerable balloons), this decade featured an extended guest appearance from hometown hero Martha Graham Cracker in a yellow flapper dress and flamingo pool float; the bizarre (and totally unnecessary) schtick was that she was “skypeing in” from Las Vegas. Martha – whom Mac later acknowledged as a personal inspiration – did several numbers both solo and in duet with judy, with an air of friendly oneupqueenship prompting some particularly fine voice work from both parties. Unfortunately, save for a “free jazz” take on the fascinating obscurity “Masculine Women! Feminine Men!” and a rousing final medley including “Singin in the Rain” and Cole Porter’s “Let’s Do It,” most of the selections weren’t all that memorable.

The same was true for the next decade – the depression era – which was probably the least memorable and cohesive hour of the show. We all lined up in the aisles as patrons of a make-shift “soup kitchen” (with real soup) – we were, as Mac pointedly clarified, merely “performing poverty” – while judy and judy’s band served up some light dinner-theater entertainment, paying homage to various jazz and blues icons of the time (Ellington, Calloway, Bessie Smith, Skip James) without much in the way of exposition or conceptual framing save for some poorly-developed banter about “poverty-induced depression.” The main highlights were Thornetta Davis – the officially crowned “queen of Detroit blues” – doing a spot-on reenactment of Ethel Waters/Alberta Hunter’s bawdy blues hokum “My Handy Man” and Mac, dressed as a giant ice cream cone, singing Yip Harburg’s “Napoleon’s a Pastry,” a wry, witty and eminently relevant commentary on branding and commercialism.

Early on in the proceedings, along with judy’s recurring maxim “everything you’re feeling is appropriate,” Mac cautioned us that “if you ever feel like hunkering down into one emotion about the show…don’t” – which turned out to be apt advice. After a fine and engaging (if disorienting) start, the show seemed to settle into a bit of a lull during the 1920s and ‘30s (despite plenty of unexplored historical and musical potential – there was no mention of prohibition, for instance, or the New Deal, and the rich mythology of freight-hopping dustbowl hobos got fairly short shrift despite a fine run through Woody Guthrie’s “I Ain’t Got No Home.”) But that dry spell turned around dramatically in the fifth hour/decade of the show – 1936-1946 – which was perhaps the most consistently intriguing, complex and well-crafted hour of the entire day. Likewise, although Mac quipped about the danger of “losing the audience” when judy started railing against parenthood and domesticity, judy’s exploration of those themes in this era was – at least for this particular cis-het married parent – part of what brought me emotionally back into the show.

Taylor Mac | photo courtesy of the artist

Taylor Mac | photo courtesy of the artist

After an uncharacteristically straight (in every sense) transitional rendition of Hoagy Carmichael’s “Stardust,” performed by Mac’s indispensable bandleader, pianist and musical right-hand man Matt Ray, judy reappeared, flanked by a Mt. Rushmore-headed Machine Dazzle, in the most astonishing outfit of the day thus far – a Pollock-splattered army-green kimono/apron number with the wings of a WWII bomber, complete with functional, spinning propellors, and a headpiece made of slinkies and smiley-face ping-pong balls – to launch decade five with a stirring rendition of “The Trolley Song” from Meet Me In St. Louis (perhaps the day’s first, but definitely not the last nod to judy’s pronounsake.) That led into the domestic fantasy of “Tea for Two,” during which several of the Dandy Minions – a panoply of radical queer performer-types, many of them locally-sourced, who served as all-purpose stagehands and a de facto chorus – emerged in beach-ball-bellied pregnancy drag, exaggeratedly miming morning sickness, back pain, farts, etc. What followed – Mac’s utterly committed, bravura performance of the Billy Bigelow “Soliloquy” from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel – was perhaps the single most powerful, transfixing moment in the show. I know it was the one moment that actually made me cry. The song is a free-form rumination on impending parenthood that reflects just about the most extreme and exaggerated vision of restrictive mainstream gender norms imaginable; Mac introduced it simply by saying “this song traumatized me as a child” – and its not hard to hear why.

And then, immediately following that moment of unexpected pathos, with all that it expressed and left implicit about the psychological violence of gender socialization in this country, I was back up onstage again, dancing the Lindy hop to a tune called “Pachuco Boogie” with New Yorker named Cassiope. (Our pants were well-coordinated.) Mac had issued the call for any swing dancers in the audience to come up and take on the part of Chicano “zoot suiters” at a party, setting the scene for judy’s recounting of LA’s 1942 “Sleepy Lagoon murder”, the ensuing, racially-motivated Zoot Suit Riots and the formation of the Sleepy Lagoon Defense Committee – a telling which somehow also managed to incorporate an audience-participatory pregnant-zombie attack dream sequence. The decade closed with another showstopper: a vividly orchestrated rendition of “Ghost Riders in the Sky,” slowed down to an ominous bolero, which folded in a poignant recitation of W.H. Auden’s startling poem “A Walk After Dark.”

After an onstage costume-change (polka-dot bikini, suburban-domesticity paper-cutout skirt, white-picket-fence stole, and a bouffant wig made out of 3-D movie glasses) set to Roy Orbison’s “Oh, Pretty Woman” (actually from 1964, but whatever), we arrived at one of the day’s defining bits of audience engagement. To represent the era of suburbanization and white flight, all white people in the house were instructed to crowd into the side sections, while the audience members of color stretched out in the conspicuously depopulated center section – all, fittingly enough, to the tune of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ “I Put A Spell On You.” The rest of the ’46-’56 decade – in a foreshadowing of what was to come – was somewhat narrowly focused on the isolated experience of queer (white) teenagers in mid-century suburbia, with the musical selections – alternating between hip (Johnny Cash’s “Folsom Prison Blues”) and square (Patti Page’s “Mockin’ Bird Hill”), and including some relatively deep cuts by Connie Francis, Dean Martin, Elvis and Chuck Berry – mostly chosen to serve the narrative rather than for any specific historical or cultural significance.

Taylor Mac | photo courtesy of the artist

Taylor Mac | photo courtesy of the artist

When it comes to the 1960s, of course, historical and cultural significance would be hard to avoid even if you tried. The 1956-66 decade – which focused, naturally enough, on the Civil Rights Movement (more specifically, the 1963 March on Washington and its queer co-organizer Bayard Rustin) – opened with a pop-art bang: Mac floating high above the stage on the wings of a comic-book finger-snap, in a dress that combined Lichtenstein, Warhol, Jasper Johns and Jackie O, singing the lyrics of “Turn! Turn! Turn!” to the driving beat of the “Peter Gunn” theme. (This moment also marked the halfway point of the day’s performance, or the three-quarter-mark of the show as a whole.) From there on, there was a clear resonance to both the more obvious picks (The Staple Singers’ “Freedom Highway”; a thunderous tear through Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddamn”) and the less overtly political likes of James Brown’s “Think,” the Supreme’s “You Keep Me Hangin’ On” (one of several tours-de-force from backup vocalists Thornetta Davis and Steffanie Christi’an) and “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood” (a brilliant song choice for a segment in which we white audience members were invited to exorcise our white guilt by performing it at exaggerated length.) The decade’s biggest revelation, though, was a solemn and quietly searing rendition of Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” – all five vitally evocative verses of it.

From that point on – following a palette-cleansing, crowd-hyping guest appearance from the Camden Sophisticated Sisters (and Distinguished Brothers) drill team and the Almighty Sound Percussion Drumline – the show’s trajectory became increasing narrow and pointed, with the final five decades focused almost exclusively on queer history. Save for the aforementioned bit of Cold War cock-sparring (which, you know, was not exactly not queer), there was virtually no overt mention of larger national or global history from 1966 to the present. 1966-1976, of course, brought us to the decade of Stonewall riots and the gay liberation that followed, a historical narrative which Mac presented largely reverently albeit with a surprising amount of mainstream classic rock: “Born To Run” sounded the keynote (with “Marsha” – as in Johnson – subbed in for “Wendy”); “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” naturally, served as the processional for a symbolic reenactment of Judy Garland’s funeral (wherein audience-sourced pallbearers carried an audience-sourced Garland through the theater while black-veiled Minions scattered rose petals); a full-blooded “Gimme Shelter” soundtracked the uprising itself (after “White Riot” was cut short for being insufficiently intersectional), and Bowie’s “Oh! You Pretty Things” signaled the celebratory aftermath. (The only real curveball came with the strange sci-fi reverie of Patti Smith’s “Birdland,” performed in near-darkness with a stark spotlight on Mac’s disco-ball headdress.) As the decade ended I was back onstage again, for the final time, slow-dancing with a same-sex stranger (along with everybody else in the audience) to an ironic “appropriation” of Ted Nugent’s flamboyantly homophobic “Snakeskin Cowboys” – a song Nugent openly admits was written about the “fun” of gay-bashing – recast as a romantic “gay junior prom” ballad.

Taylor Mac | photo courtesy of the artist

That moment of beautiful subversion and communal intimacy led us, via an inspired mash-up of “Kashmir” and “Stayin’ Alive,” into the home stretch; a decade that, while delving into the specific subcultural nuances of the post-liberation gay sex party scene, also turned out to be more or less the final time that Mac engaged with widely familiar, mainstream “popular” music at all. Actually, there were fewer songs in the 1976-86 decade than any of the others: after an extended meditation on public and private shame set to the Laura Branigan’s disco earworm “Gloria” (which I never realized was, evidently, such an anthem), so much of the hour was taken up between “‘Heroes,’” “Purple Rain” and Mac’s anecdotes about judy’s own experiences with anonymous backroom sex clubs (though not during this actual era) that there wasn’t time for much else, apart from a faithful rendition of Laurie Anderson’s “O Superman,” with the audience enlisted to emulate the song’s persistent, synthesized “ha ha ha ha” pulse.

Throughout the entire show, and to varying degrees of fanfare, one musician left the stage at the end of every hour/decade. This meant that what had begun as a 24-member ensemble back in 1776 was, by 1986, whittled down to a trio; a gradual devolution whose effects were not always evident in real-time, even though there were plenty of memorable contributors (the phenomenal trumpet soloist Greg Glassman, for one) lost along the way. By the era of the AIDS crisis, however – a tragedy for which this device also served as an implicit metaphor – the effects of the diminished musical palette were undeniable: a stripped-down, transitional (and obviously thematically redolent) “Love Will Tear Us Apart” marked the departure of drummer Bernice “Boom Boom” Brooks, and we were left with just Mac (cloaked in a robe of cassette tapes, beneath a haunting troika of tinsel-teared skull masks), pianist Ray and guitarist Viva DeConcini to carry us on through the crisis. The tragic aftermath of the previous decade’s liberated sexual expression – but also the consequence of the previous two hundred-plus years of oppression and discrimination – AIDS formed the subtext for every song performed in the 1986-’96 segment, most of them relatively lesser-known selections from cult-favorite singer-songwriters: Suzanne Vega (“Blood Makes Noise”), Mary Margaret O’Hara (the magnificently poignant “Body’s in Trouble”), Tori Amos (“Precious Things.”) The closest this segment got to the pop charts was Robert Palmer’s “Addicted to Love” – its verses interpolated with Diamanda Galas’ caustic, pointedly topical spoken-word piece “Let’s Not Chat About Despair.” And the decade’s centerpiece was a triptych of songs written by gay male songwriters who were out at the time – a feat to assemble, Mac explained, as there were so few of them – including Marc Almond’s moving “There Is A Bed” (illustrated by a series of bedsheets sporting Keith Haring-esque line drawings) and the simultaneously hilarious and eviscerating “Denny (Naked)” by the queercore band Pansy Division.

Taylor Mac | photo courtesy of the artist

For Mac, who was born in 1973, this was also the era of judy’s coming of age, as a gay teenager in suburban California, which may explain the more overtly personal nature of the decade’s musical curation. Not long after coming out judyself, judy travelled several hours to San Francisco to participate in the first-ever AIDS walk in 1987, which was both a major moment of personal revelation – the first time judy ever saw another out homosexual, judy saw thousands of them – and, later on, a primary seed for the entire 24-Decade History project; a seminal instance of a community “building itself because it was being torn apart.” Thus, the ’86-’96 decade marked something of a culmination – if perhaps a surprising one – of all the layers of history that had come before, punctuated by a rousing sing-along of Patti Smith’s “People Have the Power.” The remainder of the show, while in some ways a continuation of this thread, was also something of an epilogue. The penultimate decade, 1996-2006, was even more narrowly focused both musically and thematically, featuring exclusively “songs that were popular among radical lesbians” during the era, both explicitly niche – Bitch and Animal’s “Pussy Manifesto,” Tribe 8’s “Butch in the Sheets” – and more widely heard – kd lang’s glorious “Miss Chatelaine” done as a medley with Hole’s “Doll Parts”; a run through Sleater-Kinney’s “One Beat” that was more plodding than energized (and I’m not sure it really qualifies as riot grrl) but which nevertheless provided a fine opportunity for Mac to dress as a labia-winged butterfly. With its focus on the historically specific songscape of a particular subculture – and with all the lesbians in the audience invited to come sit onstage, one last time, for a “lesbian tailgate party” – the ’96-’06 section was an unexpected echo of, and bookend to, the Jewish tenement segment that started us off eleven hours (and one hundred years) earlier.

Taylor Mac | photo courtesy of the artist

Closing out the decade, as a final nod to whatever “popular music” even means anymore, was a minimalist but satisfying piano-and-vocals take on Lauryn Hill’s “Everything is Everything” (from an album that was popular with radical lesbians insofar as it was popular with everybody) which served as Matt Ray’s swan song, the show’s only real acknowledgement of hip-hop and, despite being twenty years old, as timely a selection as ever in this year of “Nice for What” (heck, there was even a Lauryn Hill cover at the Justin Timberlake concert I went to the week before.) After that, the final hour – a further deconstruction of the show’s elaborately-established format – truly felt like a postscript: Mac, visibly tired but still in fine voice, alone onstage in one final Machine Dazzle creation (a giant vagina which transformed into a glistening pink ball gown), performing a series of original songs on banjo, ukulele and piano. (More than anything, Mac’s delightfully witty, self-aware songs reminded me of Stephin Merritt – another brilliant, polymathic queer with a penchant for elaborately structured, improbably epic and encyclopedic musical projects, and with not-dissimilar tastes albeit of decidedly different temperament.) Per this set’s playfully meta opening number, “In the 24th Hour,” these songs served less to tie a bow around all that had come before – obviously an impossible task – than to offer scattered commentary on various aspects of it, as well as other sundry topics (the distortions of communication in the social media age; the fate of radicalism in a post-liberation landscape; the overly romanticized “sacred cow” of missing people.) The repeated final line of the final song – which thus stood, serviceably enough, as a culminating mantra for the show as a whole – was: “you can lie down or get up and play.” After twelve exhilarating hours, most of us in the audience were surely more than ready to do the former, at least in the immediate short-term – but no less inspired to do the latter.

Taylor Mac | photo courtesy of the artist