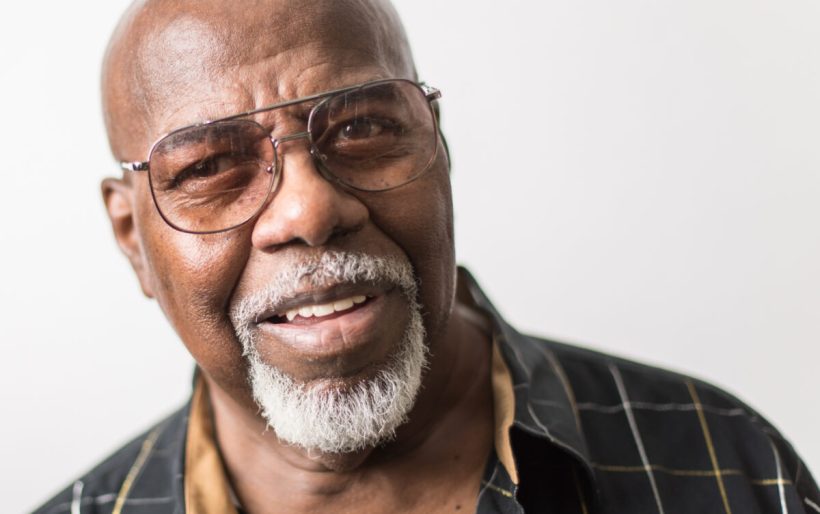

Garnet Mimms | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

The High Key Portrait Series: Garnet Mimms

“High Key” is a series of profiles conceived with the intent to tell the story of Philly’s diverse musical legacy by spotlighting individual artists in portrait photography, as well as with an interview focusing on the artist’s experience living, creating, and performing in this city. “High Key” will be featured in recurring installments, as the series seeks to spotlight artists both individually and within the context of his or her respective group or artistic collective.

Early in 1971, Janis Joplin’s second and final solo studio record Pearl was released, and featured a number of what would ultimately become her best-known hits. Among them was “Cry Baby,” which she’d been featuring in live sets in the years prior, and which was released as a single in 1971 (b/w “Mercedes Benz”) that spent six weeks on that year’s charts.

Perhaps it was her notoriety, or her untimely death at age 27, just a few months prior, that helped to seal the popular association of that track so synonymously with Joplin, her withering blues-rock rendition reportedly a commentary on an ex-boyfriend’s departure. But, written by hitmakers Bert Berns and Jerry Ragovoy seven years earlier, the song had another life with its original performer, a gospel artist named Garnet Mimms. Backed by the likes of Dionne Warwick and Cissy Houston, Mimms put that song on top of the R&B and US pop charts in 1963, launching the singer into an international spotlight.

Mimms moved to Philly from West Virginia in the early ‘50s, at age 18, and hasn’t left the city since. He sang gospel music with his church for years, and eventually joined the army, where he started performing popular R&B music. Then, after a rich career of about two decades singing seminal soul and R&B, and touring the world along with other legends like Otis Redding, James Brown, Jackie Wilson and Sam Cooke, Mimms would return to the church and never look back.

Well, maybe just a glance, here and there. “People call me a lot,” he admits warmly, in the living room of the East Oak Lane home in which he’s lived for the last 30 years. “People call and say ‘are you the Garnet Mimms who sang “Cry Baby?”’ Because my number’s still in the book, you know, so I get those calls sometimes.” When asked if it bothers him, he concedes, “well no, I don’t have nothing against that. They want to know about my life.”

“But it’s not what I used to do,” the singer qualifies, “it’s what I’m doing now. I’m a witness. I try to be a witness for Jesus Christ.” His reading of New Testament scripture — the way he’s chosen to apply it to his career and his life — became one of the central topics of this interview, and the prism through which he ultimately views his career and his legacy among the titans of R&B lore.

THE KEY: Did you write a lot of the songs you were known for performing?

GARNET MIMMS: I wrote a few, “Keep On Smiling,” “Anytime You Need Me,” co-writer on a couple more. With the promoters and the producers in charge — and they were songwriters also, [Jerry] Ragovoy and Bert Berns — I don’t know if you know it or not, but they didn’t accept a whole lot of other people’s stuff, they wanted to do it themselves.

TK: So they were their own hit-making machine back then. They met you in New York City, or Philadelphia?

GM: No, in Philadelphia, at a club on Spruce Street. We were singing “hot gospel,” what you called “hot rock” in a club – hot gospel in a rock club – called “The Underground,” years ago. Broad and Spruce.

TK: Were you with a group, back then?

GM: Yeah I was singing gospel with the Edna Crockett Ensemble.

TK: So The Enchanters hadn’t existed then, by that point?

GM: No, they weren’t around then.

TK: When you met those guys, they wanted you to perform what they’d write for you. Were they out specifically scouting for singers?

GM: I imagine they were, you know, I know Ragovoy was there one night. And Bill Fox — I don’t know if you remember him, real estate broker — he was our manager, you know, and he introduced us to Ragovoy and Bert Berns, and whatnot.

TK: How did you get hooked up with Bill Fox, with a real estate guy?

GM: Yeah well, we were singing and he was interested, and he told us he could actually do something else for us.

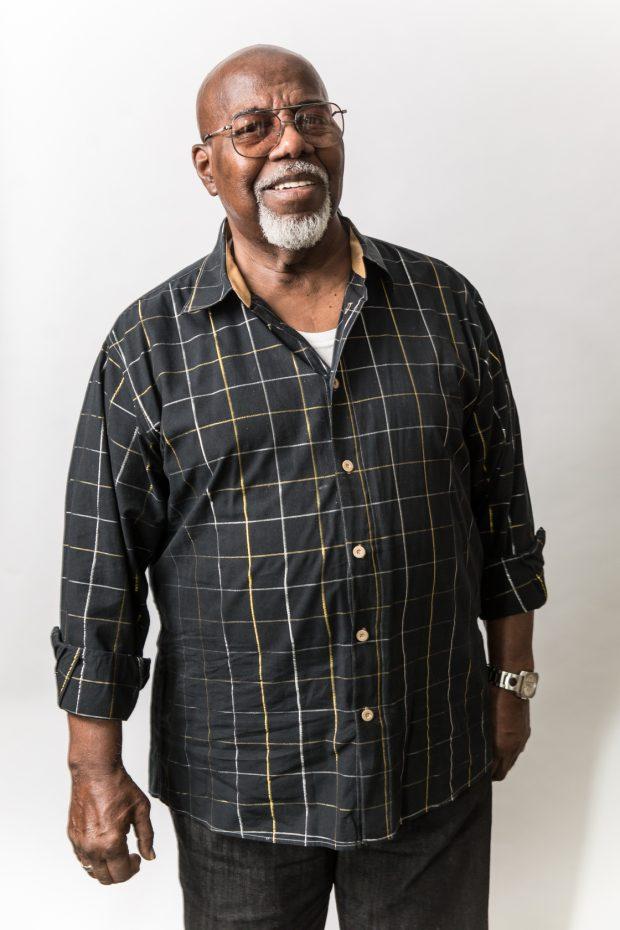

Garnet Mimms | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

TK: I’m interested in the connection between gospel and pop music and when you started singing what you called “hot gospel” — that was church music that you were taking to the clubs, essentially, is that right?

GM: Right.

TK: You were one of the first people that were doing that kind of thing. You were working at Temple University at the time, I understand you heard the radio, listened to guys like Jackie Wilson or Sam Cooke, right, people who were originally singing gospel. How did you decide to kind of take it to play out a clubs, that there would be an interested audience for that kind of thing?

GM: Well it wasn’t my idea. It was Edna Crockett’s and Sam Bell’s idea.

TK: They were in Philly at that time also?

GM: Yeah, I knew them and I started singing with them.

TK: How’d you get connected with them?

GM: Well, I sang gospel all my earlier career. I sang with The Evening Stars, and Sam Bell was a member of The Evening Stars.

TK: So these were all folks that you’d met at in your church community, singing gospel music, right?

GM: Yes.

TK: And so when you had taken “hot gospel” to the clubs, you were actually seeing gospel music and not “pop,” or with pop themes. At some point there was a conversion to pop, and the stuff that Ragavoy was writing. Was there any conflict, any clash of culture that you felt, having come from the church?

GM: Well, first of all, I had gone into the army [in 1956] before all this took place. And after I went into the army, I didn’t sing gospel again until later on. I went into the army and I started singing rock. And when I came out I ran and got Sam Bell again, and we started doing certain things. We had The Gainors, and we did several doo-wop songs. And then we finally met Bill Fox, and Jerry Ragovoy and Bert Berns, and that’s where I came from.

TK: So when you were singing singing rock music, what kind of what kind of songs do you sing in the army?

GM: Well we start singing Little Richard, “Send Me Some Lovin’,” Sam Cooke, “You Send Me.” And I wrote quite a few songs in the army, and I sang my own songs. I had a group called Garnet Mimms and the Deltones.

TK: When you came back from the army to Philadelphia, what neighborhood did you live in at that point?

GM: In North Philly, right off of 19th and Allegheny.

TK: What do you remember about your first time playing in a club in Philadelphia, about your first audiences here. How did it feel to be on stage?

GM: Yeah well it was different, because I always sang gospel before.

TK: Was it a warm reception, were you nervous, what were the the first feelings that you had on stage?

GM: Nah I was never nervous, not from a kid. I remember when I was with — I think it was The Gainors — we sang at JFK stadium in South Philly. We had a hundred thousand people, I think it was. I was never nervous, I can honestly say.

TK: What was the audience like, at the first clubs you played, what was the demographic?

GM: It was mixed.

TK: And how do you remember the reception of you being coming from gospel, was there any kind of skepticism, in your transition from gospel of pop at all?

GM: No, I never heard nobody say anything, you know, just just my own feelings, I guess [laughs], you know.

TK: So what were those feelings, how did you feel about being up on stage singing pop music?

GM: I mean, well to be frank I had met them — Jackie Wilson, and I met Sam Cooke when I was like 22, 23, when he was with The Soul Stirrers, when I was singing gospel. Anyway, I saw these guys, I said, these guys are no better than I am, I think I can sing just as good as they can, some of them. And their names [are] in lights — I want to see my name in lights too. I had that ambition.

TK: Where did you meet them?

GM: Sam Cooke? Sam Cooke was singing lead for The Soul Stirrers, and I was with The Evening Stars, and we toured together, back in the ‘50s.

TK: What was that like?

GM: It was great! We had a good time.

TK: Did you know him personally, did you spend time with him outside of the shows, go out to clubs or anything?

GM: I knew Sam personally, yeah. No, not then, because we were all singing gospel then. Now, before Sam died, I was on Sam Cooke’s last tour, and we we we talked more then than I’d ever talked to him in all the days, you know, and that was 1964. I met him in 1954, ‘55, and he was with The Soul Stirrers, and we toured together and talked. That was all gospel stuff then, you know.

TK: Was Philadelphia one of the stops for that for that tour?

GM: Yeah, at the Met, Poplar Street.

TK: Do you remember that show pretty well?

GM: Oh yeah! Yeah I remember all of those! We had a thing, you know like, who would be the best. It was a competitive thing, you know. And I know Sam Cooke had a unique type of voice and he was gonna tear the house down, you know. And, The Dixie Hummingbirds and Ira Tucker, and June Cheeks and the [Sensational] Nightingales, and myself and The Evening Stars — we had the type of voices and the type of music that would really get the people going, you know.

TK: Were you surprised, when you heard about Sam’s death?

GM: I was shocked man, that took me out. I’ll tell you. I never will forget it, it was on a Friday morning when I heard, I was on my way to New York to open up at the Apollo Theater, and I just couldn’t believe it. I just had left him a few days ago! Tour ended in Dallas, Texas. I came home, he went to California. Next week. I was booked in New York, and oh, when I heard that, that was that was really a shock. I still can’t believe it!

TK: And, Jackie Wilson, what was that like?

GM: [laughs] That was my buddy, that was a crazy guy. Oh, we had a good time together, Jackie and I, a lot of times.

TK: Did you play in Philly as well with him?

GM: Jackie? Yeah. At The Uptown.

TK: What was he like?

GM: Jackie was a nice guy, he was wild, kind of wild, you know. A happy-go-lucky kinda guy, you know. He was a nice guy though. Good.

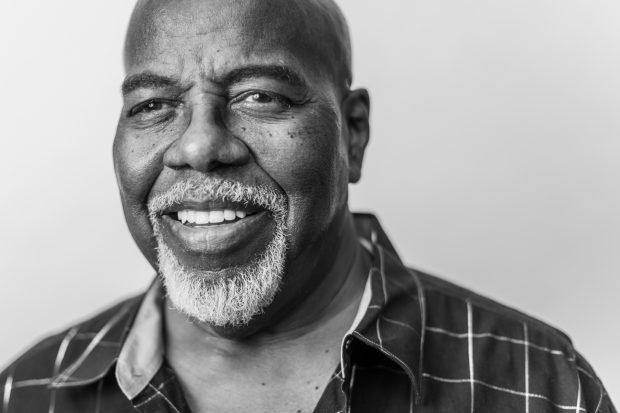

Garnet Mimms | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

TK: When you were playing in Philadelphia, did you do a lot of different clubs in the area?

GM: Well, The Uptown, there was a club called Garibaldi’s I used to do quite a bit, up on Chelten Avenue, and there was a club in South Philly I used to do. And I did a lot of stuff in Jersey — Loretta’s High Hat, all the time, over there..

TK: How long was your partnership with Ragovoy, maybe 10 years?

GM: Yeah I was with Ragovoy, from 1963, yeah about 10 years. I went to Verve, I went to GSF with Larry Newton. Yeah, about 10 years.

TK: At one point, I guess in the late ‘70s, your father passed away, is that is that what happened?

GM: My father, yes.

TK: And that that impacted your outlook, I guess you had you had a shift in priorities, as I understand.

GM: Yeah, yeah. A big change in my life there.

TK: Could you describe your consideration of why your focus left pop, and went back to the church, and why you kind of gave up singing pop music?

GM: Well, it wasn’t a situation — you might not understand it, but I got saved. The Lord saved me. That’s something that only you can understand yourself, when it happens. You know, I had gotten tired of all the stuff anyway. When disco came out, I definitely was tired of all that stuff. I said I can’t make this, you know. But I did do a disco record, after my father died, in ‘78. It was on my last LP that I did, Garnet Mimms Has It All, and [producer] Jeff Lane, and the Truckin’ Company, “What It Is.” And it started going up the charts, I said aw no.. [laughs] I can’t still stay out here like this. I can’t be singing this stuff, you know.

TK: So, you were you were intimidated by your own disco success?

GM: [laughs] yeah…

TK: When you went back to church you became a pastor?

GM: Well, I became a preacher, I’m a pastor now. Three years after I got saved, you know, my wife, my daughter and I, we did a lot of concerts — South Carolina, North Carolina, all around Philadelphia, everywhere — we were singing gospel. Then later on I started preaching, about 1984.

TK: And were you still singing at that point, or you gave up singing?

GM: Oh no, I never gave up singing, I sang gospel.

TK: Are you still singing?

GM: Yes.

TK: You are. At which church?

GM: At my church. I’m at 8901 Ashton Road, up in the Northeast.

TK: Are you singing in a gospel choir now, or solo?

GM: No, I just sing by myself.

TK: In terms of the arts community in Philadelphia, when you consider your experience with other artists in Philly or the community that you knew in Philly that you were involved with, what did you feel to be the biggest advantage or distinction of being an artist in Philadelphia specifically? Did you feel like it was a benefit to you to be in Philly, did you feel they were unique attributes of this city that impacted or informed your experience as a singer?

GM: I guess Philadelphia was alright with me. [There’s] a lotta artists here in Philadelphia that I had known — Lee Andrews & the Hearts, Chubby Checker, and quite a few of the artists here in Philly, you know I met them. But I don’t know, I don’t think there was no advantage by me to be in Philly. Everybody thought that I was from New York somewhere.

TK: Why did they think that?

GM: I don’t know! I just don’t know. Everywhere I went, everybody thought I was from New York.

TK: What was your experience with Lee Andrews, do you remember playing with the Hearts?

GM: I never played with him, no, but I knew him, and I talked to him on several occasions. And as a matter of fact, I got an award, the Lee Andrews award — he wasn’t there to present it to me — a couple of years ago at the FOP. But I received that award. That was nice, I liked that.

I liked him. There weren’t too many people that I didn’t like. I got along with a lot of people, you know. One guy that I didn’t get along with was James Brown. I didn’t get along with him. I didn’t like his act. I didn’t like his ways. I didn’t like his personal acts with people, I just didn’t like that. He was professional. But I think he let that go to his head and, he didn’t treat people right, you know.

TK: Did you tour with him?

GM: Many tours with him really. When “Cry Baby” first came out, I did several tours with James Brown. I just didn’t like ‘em.

TK: So you were touring, and there’s a lot of fame all the sudden. You came up from the church singing gospel music as a kid, and then there was a transition to some kind of fame or popular reception of gospel or the pop music that you started singing. How do you remember that feeling around that fame, that change to being on the pop charts and the shift to commercial success?

GM: Well, I guess I go back to, you know, remember, I wanted to be like those guys, my name in lights and on the charts and stuff like that, and I said, well, my dream has come true. This is it. You know, my mother didn’t like it at all [laughs]. No, she wanted me to stay in gospel. “What are you doing, son?,” you know. But anyway, it was a great experience for me.

TK: So was she skeptical of it the entire time? How long was your mother around for to see that part of your career?

GM: Well, my mother wasn’t around very long, she passed away in 1984, the year that I started preaching. But you know, the time before, when I when I was singing rock, she was always there. She was still in the church, and back in ‘63, ‘64, ‘65 — all through the ‘60s and ‘70s — she didn’t like it. She says, every time I went overseas to England, she says “I’m praying for you, I’m gonna keep you in prayer!,” you know.

TK: Did she come to your shows that all?

GM: One time.

TK: In Philly?

GM: No, it was in Baltimore. And I was on tour with James Brown and she said “oh, that’s crazy! I can’t stand all that screaming and hollering going on.” [laughs]

TK: So she didn’t like she didn’t like the show.

GM: No, no. She said, “I know you went astray.” [laughs]

TK: I guess she must have been happy that you were kind of considering moving back to gospel music and stepping away from from pop, then?

GM: Oh she was ecstatic, when I got saved and came back to gospel! Yeah!

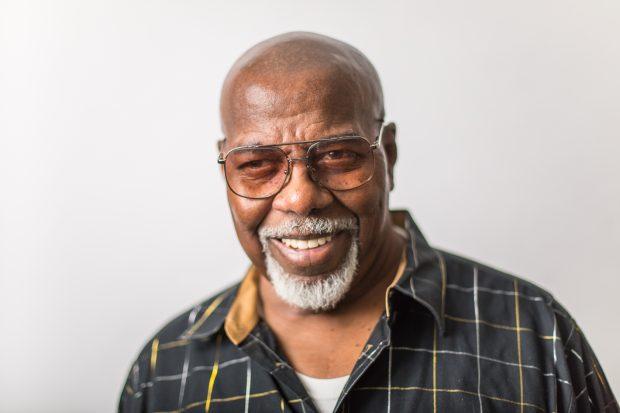

Garnet Mimms | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

TK: What was different about about European audiences and about the reception to gospel?

GM: Oh yeah, well they loved it! You go over there, then — and I went over there 1966, I think it was — I was like a king, over there! The black artists that went to England around ‘66, ‘67, they were tops. They just loved it. The clubs were packed and, you couldn’t go nowhere without ‘em, they were right there for you, you know.

TK: Motown artists, too, you must know some of those guys.

GM: Oh yeah I knew all those guys, all the Temptations, and Smokey and the Miracles, Supremes and Diana [Ross], Marvelettes, I knew all of them. Martha Reeves and the Vandellas.

TK: What was the understanding of Elvis Presley and the white artists that essentially made black music really much more popular among white audiences, and sort of appropriated some of black culture and black roots music and gospel music and blues music — what was the reception in the black community about that? Was there a resentment, or was there was an appreciation for being more broadly commercialized?

GM: I heard people talk about, Presley and Tom Jones, said they stole our music and whatnot. Little Richard declared that Elvis Presley and all of them weren’t the greatest, you know but, that didn’t bother me at all. Didn’t bother me at all. Music is music. I believe that music is the voice of God. It’s an international language, understood by all mankind! That’s what I believe, you know. No matter what kind it is, people understand it in their own agenda.

TK: Led Zeppelin covered one of your songs, and more famously Janis Joplin — did you get to did you get to meet those guys ever?

GM: I never met Janis Joplin, and I never met the Led Zeppelin. But they did they did a great job on ‘em! I think Janis Joplin did a great job on “Cry Baby.” As a matter of fact, I know she sold more copies than I did — I only sold a million, I think she sold about ten [million]!

TK: Did you have a favorite Philly venue to play at when you were playing in Philly?

GM: No, not that I know of. I was just at The Uptown. And most of the time, most of my whole career as an artist, from 1966 when I made my first tour to England, I didn’t play in the United States a whole lot. I went there a lot. I stayed over there a lot, I did 12 tours over there. And if I did anything in Philly, it was just momentarily, just for a hot shot, but I stayed in the South most of the time, from Richmond, Virginia all the way through to Florida. And that’s where I worked at, most of the time.

TK: And why was that? You were home in Philly in a sense, but you was it better commercially to play the South?

GM: Well, you know, you’re always received better in other places. [laughs] I quote the bible, Jesus said, you know, you’re not accepted at home, very often, you know, people want somebody else. But anyway when I was outside of Philly, I was more accepted, all the way down from Virginia to Florida, really.

TK: Well, do you think that was because gospel music was bigger in the South, or that wasn’t part of it?

GM: Well I was singing rock then!

TK: Right, but it was gospel-rooted, right, I mean it was it was a form of music that was popular from the South.

GM: Well gospel music was always popular in the South! But you know, the music that I was singing, R&B, a lot of it was clubs, man, a lot of clubs — Greensboro and, Durham, North Carolina, and Virginia, Georgia, South Carolina, Florida, Alabama — I was always down that way and it was very popular down there, you know. They had a lot of clubs and they had people come in, you know. I did some things down there with Otis Redding and, Gene Chandler, we did we did quite a few stops down there.

TK: What was it like working with Otis?

GM: One of the greatest guys you ever want to meet.

TK: Did you did you guys ever collaborate on anything, or just play around in the studio or anything like that?

GM: No, we never did. We never did. [laughs] I after I have that covered Jerry Butler’s “[For] Your Precious Love,” Otis told me, “I’m gonna do that song. I’m gonna do that, Garnet.” He did it!

TK: You lived in North Philly, have you lived in anywhere else in the city besides Oak Lane?

GM: Well in 1964, I moved to West Oak Lane — up on Kemble Avenue. And from there, I moved here, 1980.

TK: So you pretty much stayed in the same general area of Philly, then. You’ve seen it change tremendously, I imagine, in that time.

GM: Oh yeah. Yeah.

TK: In what ways?

GM: Well the neighborhoods have gotten worse. North Philly, where I came from, is really where it’s just really bad, you know, I don’t even go there no more. Kemble Avenue is pretty good. I sold my house to a young lady that was a Christian and, she keeps it up, I go by there every now and then. And I know her too, you know. But, North Philly’s still North Philly. I believe all of Philadelphia is rough, at times, you know, ‘cause we have killings and stickups and stuff up this way also. We had a killing up here — right around the corner there, really — at a Asian market, round the corner there — they killed a guy. But I guess I just stay in, mind my business, and do what I have to do, you know. Yeah.

TK: Were you affected by any of that the violence at any point, in North Philly?

GM: Never bothered me. I remember one time when I was younger and in North Philly, when I first came to Philadelphia, they tried to make me join a gang. And the gangs back then, you know, I said I ain’t joining no gang. And they tried to initiate me, and I got in a big fight. And, I won. [laughs] I didn’t join no gang, but I didn’t have to leave the neighborhood either. But I didn’t join no gang.

TK: What year was that?

GM: 1953. [I was] 19.

TK: I’m curious about your return to the church. Did you still did you know the folks that you went back to work with again when you started working the congregation, or where you new to them?

GM: Did I know the people in the Gospel world? Yeah. Well, some of them! Some of them. I knew Pastor Johnny Golden. Lee Chapman. Quite a few of the people, I still knew. They were glad to see me return.

TK: Do they ever ask for your hits?

GM: They knew ‘em all. You know, sometimes — even just last Sunday — I went to another church to preach, and the pastor got up there and said [sings] “cry, cry baby!,” [he said], “I know who you are!” [laughs] They remember. Just about anywhere I go and they hear the name, they know the record.

TK: And so do you ever sing them at church?

GM: I never sing rock no more. I never sang it since 1980.

TK: Really. How come, I’m curious.

GM: Well I started reading the Bible, and Jesus said you can only have serve one master, you can’t “serve God and mammon.” And either you’re with me or you’re against me. And I believe that. I believe the Bible, and I just believe that I should not do that. Case: I went to California in 1999 — you might want to know this — to receive a Pioneer award for being one of the best singers in the ‘60s. So they were saying to me, “we want you to sing ‘Cry Baby.’” I said well I won’t sing “Cry Baby.” I don’t sing “Cry Baby” no more, I’m saved, I’m a preacher, I don’t sing rock no more. So they said well, you get $15,000 to sing it. I said, well you could take that, I don’t want it. But anyway about two months before I was supposed to come to California, they called and told me, they said well the organization has paid for your ticket, you and your wife, if you wanna go. So you going to California anyway. So I said, okay, I’ll go out there — I wanted to go to California, I hadn’t been there in a while — so I went and once I got there they said well you gotta sing “Cry Baby!” I said no, I’m still not singing “Cry Baby.” [laughs]

So it was ironic, you know, like when they introduced me — it was the Rhythm & Blues Foundation, you know, that had me out there — and when they introduced me I went up there and they gave me my Pioneer award, and they said well are you gonna sing “Cry Baby?” I said no, I’m not gonna sing “Cry Baby.” But you know, you make a little speech after you receive an award, I said “I wanna give honor to my Lord and savior Jesus Christ who is first and foremost in my life. They want me to sing ‘Cry Baby’ and I don’t sing R&B no more. But you will hear me sing again, because I’m going to do a gospel CD, then you’ll hear me sing again.”

And it was very quiet in there. So I got ready to walk off, and Cissy Houston, Whitney’s mother — a lot of people don’t know this, but Cissy Houston, Dionne Warwick and Estelle Williams sang top on “Cry Baby.” It wasn’t the Enchanters! Anyway Cissy Houston said “wait a minute, Garnet, we got something for you!” And they gave me the check for $15,000! I said thank you, you know! [laughs] Now I attribute that to being a blessing, because I did not compromise my convictions. You know what I mean? You follow me?

TK: I follow. But I’m curious about about your perception of, I guess, you got people like Aretha, or a lot of pop singers who sang pop music and came from the gospel music tradition. I am assuming that that you don’t have any judgment toward them for continuing in pop, whereas you turned away from pop to stick with a conviction to serve Jesus, right?

GM: Right. I asked Eddie Holman — Eddie is an assistant pastor of a church right here in West Philly, and I was at his church one Sunday — and I asked him, I said Eddie, I said, how do you feel about going to England and you’re singing “Hey There Lonely Girl,” and your pop records and whatnot? He said well, Garnet, that’s the way I make my money. I said, but how’s your relationship with the Lord? He’s said, “God told me it’s alright!” That’s it! Case closed! If God told you that, I ain’t got nothing to do with it, you know what I mean? He said God told him it was alright!

TK: But for you, God told you it’s not alright.

GM: My personal conviction. I tell everybody that. That’s my personal conviction. I don’t know judge nobody else. That’s my personal conviction.

- Garnet Mimms | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- Garnet Mimms | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- Garnet Mimms | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- Garnet Mimms | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- Garnet Mimms | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- Garnet Mimms | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- Garnet Mimms | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- Garnet Mimms | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- Garnet Mimms | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- Garnet Mimms | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- Garnet Mimms | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN