Preserving History: Max Ochester of Dogtown Records and Brewerytown Beats on uncovering hidden gems of Philly’s musical past

Max Ochester of Dogtown Records and Brewerytown Beats | photo by Yoni Kroll for WXPN

When Sounds of Liberation performed for the first time in 40 years back in mid-June opening up for the Sun Ra Arkestra at a jam-packed Union Transfer it was a revelatory experience for everyone in the building. For the audience there to celebrate Sun Ra frontman Marshall Allen’s 95th birthday, the joyful sounds of this group of comparative youngsters from Germantown – the core members are all in their 60s and 70s – was an immersion in the beauty of Black Liberation jazz music. For the band, it was surely amazing to look out and see so many people not just listening but totally transfixed by these songs that hadn’t been heard live in decades.

Although the music was rooted in another era, this was not a night for nostalgia but rather celebration. Founding member of Sounds of Liberation and Philadelphia vibraphone legend Khan Jamal came out and even though health issues kept him from performing, he was still received with thunderous applause as if he had just played the most amazing solo. The band, with added help in the form of Juan Diego on the vibes and local mainstay Elliot Levin on sax and flute, was there because their lost album, Unreleased (Columbia University 1973), was finally seeing the light of day.

The architect of that release and in many ways the person who had been pushing the hardest for this reunion is Mount Airy native Max Ochester, owner of Brewerytown Beats record store and Dogtown Records, which issued the album. The Key sat down with Ochester to discuss the Sounds of Liberation and their show at Johnny Brenda’s this Halloween, upcoming releases for the label, and finding the balance between the business and culture of music.

Sounds of Liberation live at Union Transfer | photo by Emily DeHart for WXPN

The Key: As far as Unreleased, do you have a sense as to who is buying it? Old heads? Younger folks? Are you sending a lot of stuff to Japan?

Max Ochester: We sent a decent amount to Japan but London is where it’s selling the most. We kind of knew that London was going to be the scene for this because there’s a big, reliable, and good jazz scene in My distributor over there, I gave him just shy of 200 copies and before street date he said we need to re-up. I was, like, “That’s cool but I don’t have anymore!” Actually I had a really hard time finding US distribution but once I did I gave them 60 copies because I wasn’t thinking that there was gonna be a lot of interest here and it turned out that they sold out immediately.

TK: What do you think the interest is over here? Is it just a music from Philadelphia thing?

MO: I think it’s a combination of a lot of things. First of all it’s a good record, it’s good music. People are very interested in not only Philadelphia music but the whole, you know, “spiritual jazz” thing and I say it in quotations because we purposefully are trying to change that term because a lot of musicians aren’t doing this for spiritual reasons. There were some but they were doing it because they love music. That’s why we didn’t say spiritual at all, we said Black Liberation music, which I think fits the time. They picked it, as opposed to somebody else picking it for them.

TK: I feel like jazz got all these terms added to it after the fact.

MO: That’s human nature, we have to describe everything and something stuck with the “spiritual” thing. I don’t mind it. I’ve seen a couple reviews come out where they’re saying that this is a “spiritual jazz” record. But in talking with the band and trying to keep this as true as possible to what they envisioned for everything it’s more that at the time period it was this Black Liberation music they were playing because they were basically black hippies in the early 70s.

I’d been working with Khan Jamal and his family directly. It was a twofold thing. [First] I got the rights to use Dogtown, which originally was never even a thing, they just kind of made it up and put it on the record. It was never officially anything.

Sounds of Liberation | photo via The Vinyl Factory

TK: What did the name come from?

MO: The neighborhood. In the 40s, 50s, and 60s it was actually gang-affiliated. There was a Dogtown gang [that] crossed between Germantown and Mt. Airy where everybody lived and so that kind of stuck. Actually, I grew up in Mt. Airy and I remember as a young kid in the 80s hearing people refer to it as Dogtown. And then Byard Lancaster, on his first record that he ever put out in 1968, he had a song called Dogtown. Then Sounds of Liberation started by Khan, when they brought Byard in they said we should put this on a label, let’s call it Dogtown.

In getting in touch with Khan and talking with the family I want to keep this again as true to the original thing as possible. There was so much of effort in that sense where, you know, the tape was from 1973 and I tracked down after a year of looking the cover artist of their first release and found a piece in his house that was dated 1973 so I was able to match that up and that worked really well.

TK: Why do you think why do you think having having that history is important? Do you think that affects the listeners ability to get more out of the music?

MO: It’s a few different things. It’s more of a selling point. People these days don’t have to buy music. But if you choose to support people like myself or other people that are doing this, what you’re supporting is, first of all you’re getting money back in the pockets [of the musicians], especially if it’s a private press situation. Most likely they didn’t make any money in the first place. Second, you’re allowing me to go and dig up the history and find the pictures and tell a story. You’re directly supporting somebody, which I think is really important. Again, I don’t have a set model of how I want to do this stuff but I do enjoy finding an obscure record, digitizing it, getting it back out there, preserving it in some way, preserving the legacy of it. So that’s that’s kind of what I did.

TK: How did that work as far as the Sounds of Liberation album?

MO: We found this tape in Dwight James’ basement of the unreleased material, and my lawyer and I talked and I said let me find out what was happening with the first record, the self-titled New Horizons thing, and it was not under contract anymore. Since I put out the unreleased thing at least one other company has gone and tried to get the rights to the New Horizons [album] but luckily I was able to secure those rights when I got the rights [to the other one]. So we do have that coming out, that’s already in the works.

TK: What’s the deal with the Halloween show?

MO: That’s going to be a great show for a couple different reasons: first of all there’s gonna be a special guest [ed. note: since announced to be David Murray] playing with Sounds of Liberation. [The set] is going to be broken up into two parts, Sounds of Liberation playing Sounds of Liberation songs but then the final part is going to be a stripped down version [of the band] which is actually the Khan Jamal Creative Arts Ensemble and they’re gonna play the entirety of “Drum Dance to the Motherland.” I don’t know if you’re familiar with that record but there were some heavy effects post-production on it and I think we’re gonna have a producer do live effects.

TK: You own a record store, you have a basement full of musical ephemera, you’re actively trying to track down all these lost records. Do you think of yourself as a collector first and foremost?

MO: My intention is to preserve, highlight, and show off Philadelphia music. I grew up in Philly and I have a tumultuous personal relationship with Philadelphia. I actually don’t think I succeed well here.

I’ve lived in other cities. I lived in New Orleans for a long time. I’d much rather be in New Orleans to be honest with you, but my family’s here, my wife and kid are here, we have a house here, I have a business here. So eventually maybe I can have a house in New Orleans, too, but there’s something about the history here and that’s something that’s always been part of what I enjoyed about Philadelphia. My dad actually works as a historical re-enactor and I think he has a lot of influence on me.

When you talk to people about Philadelphia music, they say Philly International Records, they say the O’Jays, all the big names. That’s cool but it’s so insane here. I’ve been to Detroit, New York has the same kind of thing, I’ve been to LA, I’ve been to all the big cities that have a rich musical history but Philadelphia’s history is often overlooked

TK: Philadelphia is often overlooked!

MO: Still, to this day.

TK: I’ve had this conversation a lot writing about punk bands and about how back in the 80s and 90s it was always DC and New York and maybe a band would stop in Philly.

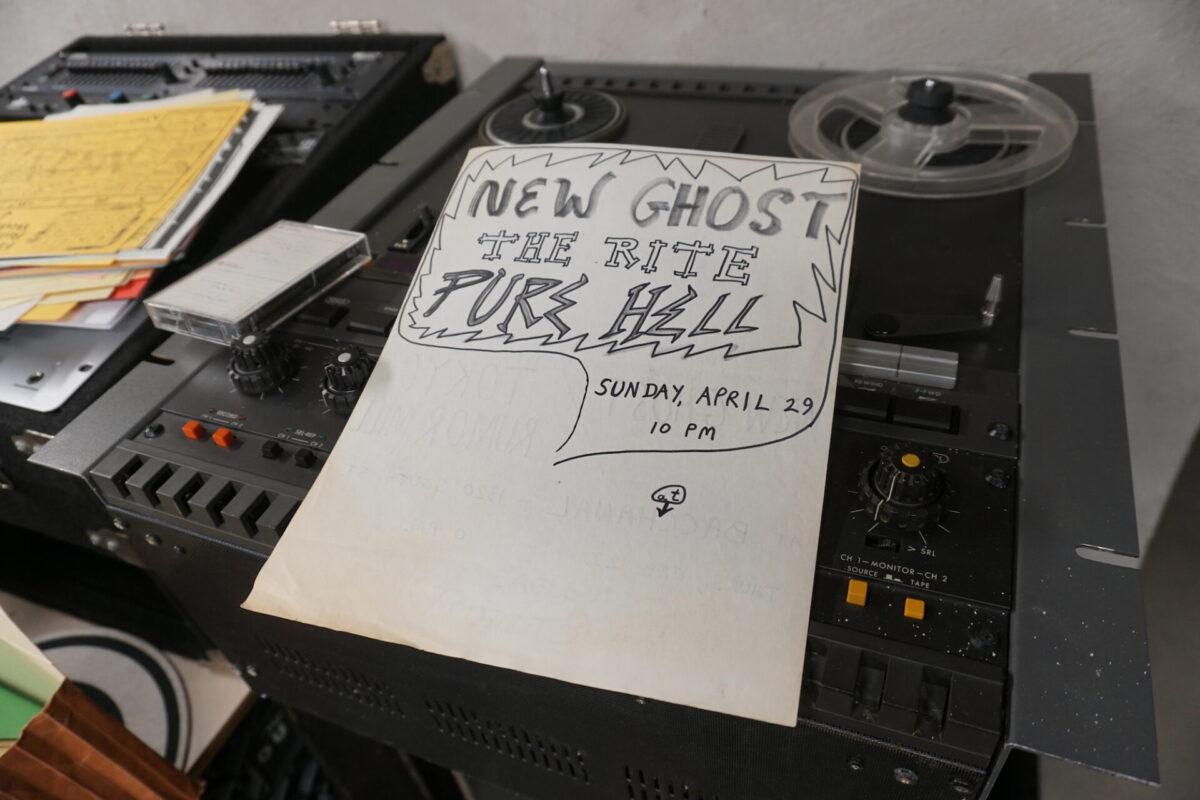

MO: I mean, we had a scene of black punk bands that nobody else really had. Pure Hell. I have a flier downstairs from Elliot [Levin]’s collection that’s New Ghost opening for Pure Hell. I’ve tried to digitize a lot of stuff but that’s the other part of it that is extremely time-consuming. I mean, I just bought a light box. I’ve got master tapes, I’ve got pictures, I’ve got fliers. That’s the stuff I try to collect and keep and preserve and digitize. It’s a whole job on top of running a record store and having a four year old. And starting a record label. It’s stupid. [laughs]

photo by Yoni Kroll for WXPN

TK: Do you feel like you got into the label business because nobody else was putting this stuff out?

MO: I have conflicting ideas about [running] a record label. We have enough mass-produced junk in this world; I’m emotionally and internally conflicted about making more. I’ve been thinking about this more and more recently. The [Sounds of Liberation album] we had to shrink wrap because we needed a UPC, a barcode, on it. So what we did was shrink wrap it and put a sticker on the barcode because again, in keeping as true to the original release as possible, we don’t want barcodes on it because this is all seventies music. So now [we’ll be] getting rid of the shrink wrap on all future releases, we’re going to do the Japanese obi strip on them which will have all our information and barcode, so that kind of eliminates a little bit of the issue. Our CDs that we’re going to be putting out are going to be 90 percent recyclable. That’s getting me a little bit over the conflict. But the other thing is I’m weighing the social and economical deficit that I’m struggling with with the emotional aspect of putting the music out there and getting it to a new audience that’s gonna hear it and really like it.

So running a record label, it just seems like a natural course for me because there is a ton of music out there and people don’t seem to be doing anything, at least in Philadelphia, with this kind of stuff. I think it’s really important to get it to people and they can decide if it’s good or not, [though] I generally tend to have good taste.

TK: Can you talk about any of the releases that you have planned?

MO: I could talk about the two that I have in. I’ve got several things on the radar [including] one next week I’m hoping to sign a contract on but we’ll see. The releases we have are the First Sounds of Liberation album. The master tapes were never available, so we are actually using the same transfer that Porter Records used in 2010. Luke at Porter gave me the transfers but I did remaster it from there. Liner notes by Francis Davies who’s pretty well-known.

TK: Are you doing the remastering yourself?

MO: No, I get Pete Humphries. He’s been doing a ton of Philly stuff forever. He was the Sigma Sound engineer for a long time. I just submitted today the Thompson Brothers, which I’m really excited about. They were four guys, three brothers and a cousin, who all grew up in this neighborhood, they grew up about five blocks from here at 25th in Jefferson. It’s a sweet Philadelphia soul record that not a lot of people have heard. It’s a really good record. It’s a love album.

TK: What year did it originally come out?

MO: 1975. The two producers, one was a musician, arranger, and conductor and the other was a producer and he just basically paid for a lot of it. They both did talent shows around the city at local elementary schools and high schools. They’re from West Philly. They went to a talent show at Vox and the Thompson Brothers came up and performed in front of them and they kind of blew them away so they signed them. Eric Ward, who was the producer, he was working at WDAS at the time and he and Tyrone, who’s the other arranger, they decided that they didn’t want to bring the Thompson Brothers to WDAS because they were afraid that somebody bigger than them was going to take the brothers away from them. So they found a studio in Sayersville, New Jersey that had recorded some other soul acts and they went up there and they did an entire album of all original compositions front to back. I don’t know how long the recording session was but hopefully we’ll find that out soon. They put an outside-of-the-city address [on it]: even though everything was done right here they put King of Prussia as their address, which is where Eric was living at the time.

TK: Are any of the Thompsons still around?

MO: I have spoken with the youngest brother. This is the unfortunate part of all this is that the brothers hold no stake in it whatsoever. They were a hired band. The producers are the ones who paid for everything, the producers are the ones that I have the contract with so with or without the brothers’ blessings I can put this out. I prefer it to be with the blessings. Not only that, [but] I’d like to get money in their pockets too, and the way I can do that is if they have pictures, if they have stories I can pay them for their time. I’m working on that. I’ve talked to the younger brother and he wasn’t in the band, he was nine at the time that they recorded the album, but he said he would get everybody together and talk. At the end of the conversation he was like, “You know, we’ll see what we can do with this” and I said, “No, I’ve got to be really upfront with you: I have a contract, I’m already doing it.” It’s unfortunate but that’s the way things happened. It sucks.

TK: From what you’re saying I feel like Sounds of Liberation might be the outlier as far as like putting something out and the band getting back together and playing.

MO: Well that’s the positive side of things. If you’re willing to work this might create an opportunity for you. And actually the younger brother Kenneth Thompson said recently that at some family gatherings the brothers had gotten back together and sung some of these songs. Hopefully they can see an opportunity to play. You know, four guys singing love songs these days is kind of unheard of unless you’re like like an old school band like the Stylistics or something but maybe that can happen, maybe they can get on as an opener for somebody. That is one positive side of it: if you’re willing to work it might create that opportunity.

That’s something we’re talking about with Sounds of Liberation is how they never owned any of this in the first place. One of the trials of the first record, the unreleased one, was that I didn’t have to get contracts with anyone. I could have paid the royalties and just been done with it. But I went and I did side artists contracts with every single person so every certain number of units that sells they get paid. We’re trying to figure out a way to get them to record again or do something again that they can all have a share of [the royalties].

Sounds of Liberation | photo by Emily DeHart for WXPN

TK: Are they gonna be playing much?

MO: Right now it’s just Halloween at Johnny Brenda’s [but] there’s some talk about a show in New York.

TK: All the members are in their sixties?

MO: Sixties, early seventies. The band at the time in 1971, 72, the youngest was 17, he was right out of high school. Two have passed now, Rashied and Bayard. Khan is sick. From the other four, Billy doesn’t play bass anymore.

TK: He moved over to keyboards, right?

MO: Yeah, that’s why he was on stage. We were trying to keep it true to the original [and] at first I was like, “I don’t want a keyboard on the stage.” But soon [that thought] became really stupid to me because why would he not be up there? It’s his band and it was great to see them play together.

TK: It was a powerful show. How did it come together?

MO: I went to Ars Nova [head] Mark Christman and I said that I’d like to get Sounds of Liberation to play a record release party and he thought for a little bit and said, “You know, Marshall’s birthday is coming up, I always do a birthday party for him. Let’s do that.” Around the exact date of Marshall’s birthday the Arkestra was in Europe for three weeks so we tried to do it as soon as possible after that. So they literally had gotten off a three week tour on Sunday night, they flew home on Monday, and they did our show on Thursday.

TK: Had they played together before?

MO: They used to play in Vernon Park in Germantown. Not like as an opener and headliner but just because they were all in the same scene. It’s interesting because the [members] of Sounds of Liberation have all spread out and done their own thing. Monette’s the most active [musically]. Dwight’s pretty active too but he’s on an educational percussion thing that he does.

TK: What’s on your list of lost records that you’d want to rerelease or even put out for the first time?

MO: Within the collective of Sounds of Liberation there’s some really cool projects. Omar Hill, who’s the percussionist – he didn’t play at the show but he’s in the band and he’s still alive, I’m meeting with him next week – he had two records from the 80s, one from 82 and one from 85. [The first one] is called Caribbean Breeze and it came out on vinyl. It’s him and Art Webb and it’s pretty much the Sounds of Liberation crew but there’s a drum machine introduced into the band so it’s got this like 80’s synth kind of sound.

Then in 85 he did a record that’s CDR-only called Tribes of the Future which is the entire Sounds of Liberation band minus the drummer with a drum machine every song. It’s really great and they do covers of “Afro Blue” and John Coltrane’s “Impressions.” It’s a killer record. What actually put that on the radar for me was when I found the Sounds of Liberation tape I found another tape that just said “Omar” on it. I I transferred both of them at the same time and listening to the Omar tape I heard outtakes that were like a B-reel of what made it to the CDR but then at the end there was an unreleased track that has this super heavy 80’s synth, like really crazy drum pattern with Byrad Lancaster on top and Khan Jamal playing and this heavy percussion. That’s something that I would really like to get out there in the world. I’m telling all my secrets!

TK: Are any bands you’ve talked to not receptive as far as rereleasing material?

MO: It’s a trust thing, for sure. I’ve been lucky with the Thompsons and Sounds of Liberation, they’ve both been so into it. When I met with the producer of the Thompsons, the first meeting we had I did the proposal, I said this is what I want to do, and at the end of it he was, like, “I’d be stupid not to do this. Nobody else is doing it, nobody has contacted me. This has been dead for 40 years. Why not do it?”

TK: Do you feel like you have a responsibility to be putting this stuff out? What do you see as your role?

MO: Not to put it out, no, but I do feel like I have a responsibility once I’m working with the artist. I think [my role] is just exposure. Carrying on a good name which involves putting out a quality product, putting out a backstory, liner notes, pictures, whatever I can do. Giving people once a unique listening experience where somebody is going to put it on and value and treasure it. A lot of times and we see it in here [at the shop] where people bring in records and are, like, “I don’t want this crap anymore” and I don’t want to see my records [treated] like that. I don’t want to see my records in the dollar bins.