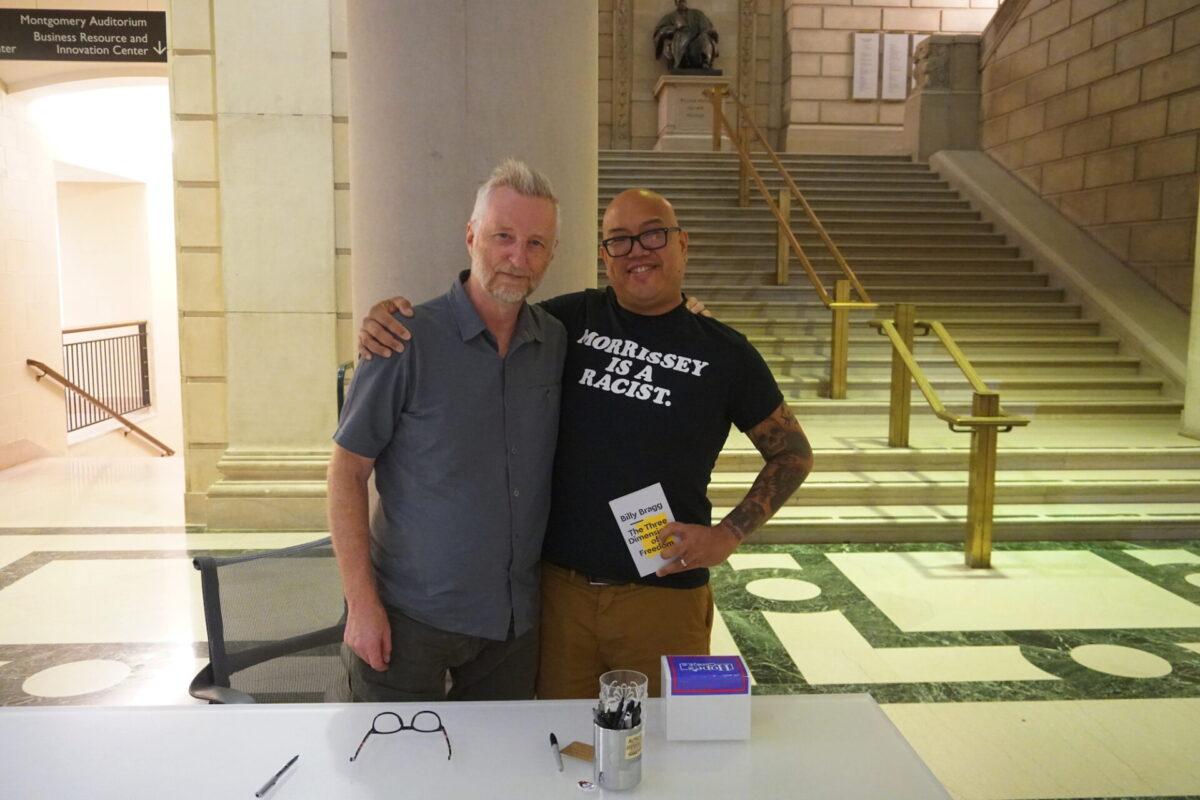

Billy Bragg at The Free Library of Philadelphia | photo by Yoni Kroll for WXPN

Billy Bragg and the State of the World: A conversation with the folk icon on the politics of nuance and accountability

On Monday night, musician, writer, and activist Billy Bragg spoke at the Free Library on a number of topics related to his most recent book, The Three Dimensions of Freedom. The event, which was presented under the Author Events series, was in conversation with WXPN’s Ian Zolitor, host of the Folk Show.

The book – Bragg referred to it as a pamphlet and at under 100 pages it’s more of a extended read – was described on the library website as one where, “he prescribes liberty, equality, and accountability as the antidote to rising global authoritarianism.”

The talk very much mirrored that, touching on everything from radical politics to mass migration to issues of free speech both online and off. On that subject Bragg, who has more than 600,000 followers between Facebook and Twitter and is not at all shy about engaging any of them in debate, noted that when someone claims to have an issue with political correctness that, “… they’re trying to control the terms of the debate.” “There’s no such thing as ‘political correctness’,” he added. “It’s a trope that’s used by reactionaries to police the limits of social change.”

To see all of this in action all you need to do is read over the viral post Bragg made on Facebook back in July calling out former Smiths frontman Morrissey’s embrace of far right wing politics. When Zolitor brought up the controversy surrounding the post the packed audience in the Montgomery Auditorium voiced their support for Bragg. He told them that he felt compelled to speak out because, “We live in a time where there is a war on empathy. I find this deeply troubling. As a musician, empathy is the currency of what I do.”

Bragg first rose to fame back in the early 80s with his debut Life’s a Riot with Spy vs Spy. Including that classic album he has released a total of 17 LPs, six live albums, and a dizzying number of EPs and singles. In 2016 he performed at Union Transfer with fellow folkie Joe Henry on the tour for their album of field-recorded train songs Shine a Light.

Before the event Bragg chatted with The Key about punk, Brexit, Philadelphia, and everything in between. While we weren’t able to talk about everything – for example we didn’t ask about the time he consumed the ashes of labor hero Joe Hill , or if there are any other radical luminaries he’d subsume – but it is a pretty all-encompassing conversation. Please check it out below.

The Key: I had read your previous book, Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World.

Billy Bragg: Not much crossover there, I’m afraid.

TK: I disagree! What I liked about the skiffle book was that it was such a good topic to look at the history of British culture, British politics, and so on over the past 70 years or so.

BB: Yeah, context is everything in a book like that. Context is everything.

TK: It’s taking a micro, in this case this pre-rock ‘n’ roll musical style, and using it to talk about the macro of British history.

BB: The cross-cultural exchange between your country and my country, immigrants in my country, immigrants to your country, that’s the sort of subtext of how music changes the world.

TK: Exactly. So your new book being about neoliberalism and globalization and the need for accountability, I think those are all things that you were talking about in the previous book but just in much different ways.

BB: The struggle to decide who gets to write the rules and who gets to break them, that goes back a very, very long way. That’s what the new book is about.

TK: What’s attractive about writing this as a pamphlet versus writing a more proper book?

BB: Well, all my favorite books on politics have been pamphlets. The Lion and the Unicorn by George Orwell, which was written in 1940, is my favorite book about English identity. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense. And as a songwriter it’s my job to keep things short. If I were to write a long book, I would have to put in a history of philosophy and all that kind of stuff when I just wanted to get to the point. Not like there’s anything wrong with that; I’m not trying to avoid it. I really just wanted it to be a burst of opinion.

TK: It’s not the Twitter version of all this but it is something that can be read and digested quicker than a full book.

BB: There’s a lot of that. If you go into bookshops now you will see a section of books on political subjects that are less than 20,000 words. When I was writing the book, I was on tour in the U.K. and, as is my wont, I do hang around in bookshops and I did notice that there are people writing books about issues like feminism or intersectionalism or free speech in short little bursts and I thought, “Yeah, that’s kind of what I’m after.”

TK: There’s always been a strong history of pamphlets in radical politics.

BB: On the continent, in France, it’s still a viable format for political discussion. Not so much in the UK anymore, we kind of lost that tradition.

TK: I remember when I was first hanging out in radical bookstores when I was a teenager and seeing pamphlets for sale and it was such a great thing because they were cheap and kind of like the fanzine version of political philosophy and political history.

BB: Like a tract. I like the idea of coming out with a tract. “The Tracts of My Tears.” I think that might be my next book.

TK: I saw that Faber is doing a whole series of pamphlets written by musicians and this is the first one.

BB: That’s right. I’m the first in that series and they asked me if there was anything I would like to write about. I had recently been invited to give a lecture to the staff at the Bank of England, which is our central bank in the UK, and I spoke to them about accountability in economics because they are tasked with distributing the government’s funds under the program of quantitative easing. I don’t know if you have that in America. [It’s] where the government gives money to the central bank to give to retail banks to give to people to try to help the economy grow.

TK: Sort of like a micro-loan?

BB: Yeah. But unfortunately, in the UK the retail banks have just used it to shore up their bottom line, they actually haven’t been lending. That lack of accountability has led to instead of entrepreneurs creating work and jobs, people with assets have gotten richer, people with shares have gotten richer, people with houses have gotten richer. But those people who are outside of the property-owning classes have not really benefited. There’s an argument there to make it more like ‘helicopter money’ and give it out directly to people to give them the opportunity to spend it in the way they would spend it rather than have it mediated by the banks.

TK: It’s interesting because despite the fact that we have all this access to information these days we’re still getting the same news over and over and over again.

BB: You can find any information to back up your opinion if you look hard enough. What is harder to do is to find information that picks apart failings in your position. I’m always more interested in that, in looking at an argument and saying, “Well, what is really going on here?” This goes on in a couple levels and is what I was trying to do in the book: not only offer people a framework with which to deal with encroaching authoritarianism, the power of algorithms, and neoliberal capitalism but also the framework with which to try and work out who is acting in good faith on their social media interactions.

TK: You wrote in the book about the nature of free speech and the “indication that social media has punctured the division between private and public freedom.” When I was getting involved in activism as an adult, and especially anti-occupation activism, there was a moment in time when the internet was giving us all these first-person narratives that were very hard to refute. But yet in the last 15 years or so there’s been no end to the information out there trying to counter those narratives.

BB: Closing them down, yeah. That’s been a huge problem in the UK particularly around the issue of Palestine liberation. Jeremy Corbyn has been a longtime supporter of the Palestinian cause, so his leadership of the labor party has drawn in a lot of people who are on that chip. So that has caused an element of difficulty for those parts of their debate that border on anti-Semitism and where that line is and trying to define where that line is. It’s possible to criticize Israel without attacking Judaism; where that line is has been very, very hard to discern due to the anger that’s flown about from both sides. It’s been very damaging for the left in the UK.

It’s the nuance of the detail that you want to talk about, and nobody is interested in that. This is the problem we have with Brexit. In the European [parliamentary] elections in the UK the parties that did well were the parties that either said “We have to leave tomorrow” or “We shouldn’t leave at all.” The parties that said “This is actually quite complicated,” those are the ones that got really hit. Labour’s vote went down to 14 percent, which normally in the European elections it’s up around 30 percent, 40 percent. The difficulty with that is not only that it polarizes the society, but if anything I want to save us from Brexit. And If anything is going to do that it’s the nuance of the Good Friday peace accords that we struck with the Irish, it’s the nuance of the Irish border, it’s the nuance of our economic relationship with the European Union. Nobody wants to talk about those things.

TK: Nuance is difficult and challenging to people.

BB: Literally today at the Labour Party Congress they voted on a policy on Brexit which says that if they’re elected in the next election, which could be before Christmas, they will go to Europe and try to get a better deal and they will put that deal to a referendum. That sounds reasonable, doesn’t it? If you’re going to have a referendum, there has to be a viable leave option on the table as well as a remain option. You can’t just have a referendum where the only option is remain. [Corbyn] is absolutely getting slaughtered because he said this. “Get off the fence!” “It’s too complicated!” “Nobody understands it!” “How are you going to explain that on the doorstep?” The Tories are saying no-deal Brexit tomorrow, which would be a catastrophe, and the Liberal Democrats are actually saying, “We’ll just get rid of it with no democratic consultation whatsoever. We’ll decide that the referendum is void.” Personally, although I want to remain, I think that’s an extreme position.

TK: But people want that binary choice.

BB: Well, the people who voted to leave should have the option in another referendum to win again. It shouldn’t just be, you know, “Fuck you.” They may win again! The polls are still very, very close, they could win a second referendum. But to then say, “We’re just going to abolish the whole thing and go back to the status quo” — which probably isn’t returnable-to because we’ve screwed the pooch there — the lack of accountability involved in that is very troubling. It’s the Liberal Democrats who are supposed to be the moderates that are saying this. But in a weird twist of everything Corbyn is now the moderate. It’s hard to keep up with.

TK: Do you see national identity ever becoming less important?

BB: I think that in a post-ideological world, people have to have something with which to connect with. In a world in which you feel like you’re in charge it’s not so much of an issue. But when it suddenly feels like China might be in charge or India possibly is going to be in charge then national identity starts coming to the fore and people start to get worried. I’m increasingly talking to people online who, two or three years ago, always disagreed with me on my Facebook page but were relatively rational. But they’re now talking about the “Great Replacement” as if [migration from Africa and the Middle East] was something that was planned by politicians rather than merely a manifestation of how free market capitalism works because people want cheap food and manufacturers want cheap labor.

TK: I think that’s another binary identity, it’s us versus them.

BB: Which again oversimplifies everything. The idea that the white working class in the UK is white is no longer true. That’s just a matter of fact and a matter of the world we live in. Demographic changes are driven by many things but the main component is freemarket capitalism.

TK: The basic nature of capitalism is that for there to be winners there have to be losers.

BB: The people who complain about about the idea that there’s been free immigration are also the people who want free markets. They’re also the people who want less labor unions. Unions would insure everybody got fair pay for their work which means it would be difficult for them to employ cheap labor which means it would be then less likely that they’d be importing people to do the work. So while it wouldn’t put an end to migration it wouldn’t be a process that’s driven by the markets, the community would have more of an agency on that.

That’s really the reason why I think accountability has become such an important issue because of the lack of agency people feel over their lives. They no longer feel like they have some kind of control over the economic situations and the social situations they find themselves in, which is why they fall for shit like the Great Replacement theory. It explains things in a way that [makes it feel like] its not their fault, they voted for Margaret Thatcher or Ronald Reagan who brought in all these free market policies that ended up with immigration rising.

TK: It’s the same thing with Trump or Netanyahu or any of these leaders: it’s the easy option.

BB: It is. That’s one of the things about social media is that it’s always looking for the master theory that explains everything. And that very quickly gets back to you know who and how ‘they’re in control of everything.’

The BBC on their new building in London they have a statue of George Orwell, who worked for the BBC, and they have a quote of his [that reads], “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they don’t want to hear.” I’m not comfortable with that. People don’t want to hear that the Holocaust didn’t happen. Let’s just simplify this to what Orwell wrote about: people don’t want to hear that two plus two equals five. They want to hear that two plus two equals four. I think that the idea that you’re allowed to say anything with no comeback and that defines what your freedom is. As I say in the book, without accountability, free speech is [to act with] impunity.

TK: That’s something that comes up again and again in the far right: that what they’re saying is free speech and they can say whatever they want because of it. And yes, they can hold a rally, but that doesn’t mean there shouldn’t be ten times as many people there to drown them out.

BB: I mean, I had a bit of a run in with Morrissey a few months ago, and he can say whatever he wants, but he can’t say it with impunity. He can’t then complain. He’s being a provocative fucker, excuse my language. Those kinds of people, like Milo [Yiannopoulos] or whoever, can’t then complain when they get a reaction that’s not a good reaction.

TK: Morrissey just played here recently, I believe to a somewhat empty space, and I was following a little bit of the online discourse about it all and people were saying how they “separate the art from the artists.”

BB: That’s what my Facebook post was about. In doing that you are legitimizing his point of view. It’s the same with the free speech warriors. They’re not interested in any type of challenge. It’s not free speech that they want, it’s free rein, and they’re angry having had that privilege all these years [that it’s] now been challenged by people from racial minorities, from economic minorities. They don’t like it.

TK: On the topic of music and the nature of the artist: in 2019, what do you think the role is of the folk singer? Has it changed at all?

BB: No, I don’t think it has changed. What has changed is the role of music in youth culture. In the 20th century, music was our only social media, though we didn’t think of it in those terms back then. That was the way we spoke to one another. When I was 19 and I was angry about the world, if I wanted to have people in Philadelphia hear what I had to say, I had to play guitar, write songs, and do gigs and hope that one day I’d get here and talk to you. Now of course, anybody can join in that conversation so music doesn’t need to play that role. But its original role has reasserted itself and that role is initially about emotional solidarity. It’s about a song being able to make you feel like you’re not alone, that you’re not the only person who has this broken heart, that you’re not the only person who has felt this particular loss, that you’re not the only person being treated badly this way. Then on top of that, it’s possible to build a social solidarity by bringing people together for a particular cause. Folk music has always been very, very good at that.

Although you can buy music – it’s cheap as chips, you can get it for nothing – the reason why more and more people want to go to gigs is because they need that communion, they need that feeling of being in a space with a load of other people and have that experience with them whether its singing “Power in a Union” at a Billy Bragg gig or singing “I’m in Love with Your Body” with Ed Sheeran. You can get that solidarity with him as well. If you’ve got a song that you love that you’ve put a lot of emotion into, a song that articulates something you can’t quite manage to say, you go to the gig [and] the person who wrote that song is singing it, there are 10,000 other people singing it, whatever emotion you put into it is immediately accepted by everyone. It feels that way, anyway.

TK: There’s an NPR series they’re running called “My Signature Song” where it’s people talking about certain songs that have followed them their whole lives. It’s never anything I’m that into, but it’s always great to hear how people talk about these songs and their importance.

BB: That’s the power of music. Music has no agency, it can’t change the world. Trust me, I’ve tried. But it does have that power, that emotional heft, and we need things like that. We need places where we can connect with those feelings in a way that does not involve altering our moods by putting horrible chemicals in our body. Music gives you that opportunity.

TK: On that note: when do you think you’ll be coming back to Philadelphia to play again? It’s been a couple years since that Union Transfer show with Joe Henry.

BB: I don’t know! I always used to play at the Keswick Theater. It’s been a while since I’ve been out there. That’s why I’m not too familiar with downtown Philadelphia, because we were always out in the boonies there.

TK: While I’ve been to the Keswick for a number of shows, my immediate association with it is how 20 years ago I got a job painting their floors.

BB: It’s a lovely theater. But it’s a long way away and there’s not much to do [around there.] I did a gig in Philadelphia once downtown somewhere where the streets are old and the soundcheck was immediately after England had been knocked out of the World Cup by Argentina in a match that involved a lot of cheating. I was absolute bereft in the soundcheck and I came out of the back door of the theater afterwards, walked down the alleyway, and it was just starting to very, very gently rain. And I got to the end of the alleyway and on the corner was a tea shop called the Pink Elephant or the Pink Tea Shop and I went in there and I had a cup of tea and a piece of cake and it made me remember that there’s more to being English than getting knocked out of the World Cup in a penalty shootout. I don’t think I would have found that in any other American city. There’s something about Philadelphia and it’s kind of obsession of reminding you that it was once part of a colony.

TK: Final question: do you see writing songs and writing books as being part of the same process or are those two separate things for you?

BB: I think my bottom line is that I’m a communicator. Whether I’m doing a gig, writing an article for a newspaper, or talking to your readers now, I’ve got some opinions and I’m trying to offer a different perspective on issues. So as Malcolm X said: by any means necessary. If I’m offered a platform I’m going to take that and offer my perspective up and perhaps learn something from other people’s comments and their perspectives. That’s the thing that’s interesting to me. I don’t really see any difference between talking to you, getting up on stage singing a song, writing a song, writing a book, talking tonight at the Free Library. For me they’re all part of the same impulse.

TK: I think part of my job as a journalist, as someone who occasionally books gigs, and as a college radio DJ is to try and elevate the voices of people who might not be getting heard. Is it similar for you?

BB: We’re all trying to make sense of the world, mate. So if you can shine a light in the corner where people haven’t been looking and draw attention to the experience of part of the community that doesn’t get its voice heard then you’re doing a good service, you’re doing a good job. Even if it is just a bunch of kids playing skiffle in the 50’s.

TK: Or in my case a bunch of kids playing punk shows in the basement right now!

BB: Yeah, exactly. It all deserves to be celebrated.

Check out the setlist from the June 30th, 1998 TLA show Bragg referenced over here.