Philadelphia Folk Fest In Place thrives during quarantine with livestreams, archives, virtual community

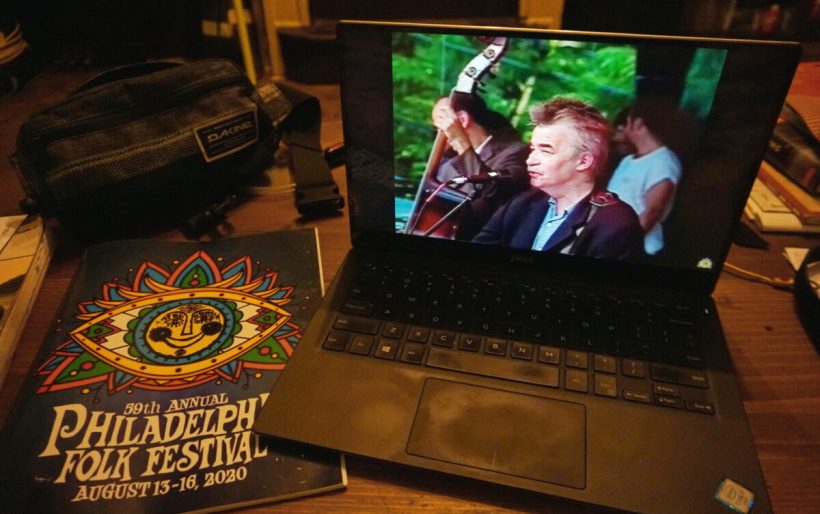

A John Prine performance from the archives plays during Fest In Place | photo by Yoni Kroll

The Philadelphia Folk Festival has been happening every year since 1962, making it the longest-running outdoor festival of its kind in the country. The three-day event brings music, culture, community, and fun to thousands upon thousands of dedicated fans who spend the weekend watching bands new and old, camping, and reconnecting with their chosen families. This summer’s fest, however, was in dire straits when COVID-19 shut down all public gatherings. After all, how do you bring together 30,000 people to Old Pool Farm in Upper Salford Township – about 40 miles northwest of the city, the home of the event since 1971 – if a gathering of more than five is basically illegal?

Easy: move it online. Well, maybe not so easy. Nothing on that scale had been done before much less while also dealing with a global pandemic and the physical and emotional environments that’s created. Still, what’s the alternative? Canceling? That was never an option according to Justin Nordell, the executive director of the Philadelphia Folksong Society, the organization that spearheads the festival.

Not only was the full lineup basically all booked – with major festivals like this, that’s done months in advance – but the bands needed the paid work, and the Fest faithful needed the show to go on. Nordell told The Key that he got many messages begging him, “Please don’t cancel, please don’t cancel. I’m suffering from intense depression, from COVID-19, and from everything that’s happening and this is the only light at the end of my tunnel, this is the only thing I have to look forward to.”

The folk community in Philly have been reeling since the deaths of longtime Folk Fest MC – and WXPN DJ – Gene Shay as well as musician John Prine, who had an incredibly lengthy history at the festival and was supposed to headline this year. Tributes for the two men, who both passed away in April, were abundant over the course of the weekend.

While there was no way to hold the festival in person, the Folksong Society has been hosting regular livestreamed concerts and other programming for the past five months out of their Roxborough headquarters and decided in April to move all three days of the event online. Nordell said that up until that point, there was hope the pandemic would have tapered off by August had everyone done “what they were supposed to in order to keep themselves and their loved ones safe. The problem was that people never did what they were supposed to to keep themselves and their loved ones safe.”

The Folksong Society weren’t just speculating about the science: they had an expert in infectious diseases to consult in Nordell’s partner (and now fiance – they got engaged on-camera during this year’s fest, which was very sweet) Dr. David Koren, Clinical Pharmacist Specialist in Infectious Diseases at Temple University Hospital.

Once the decision was made to shift the entire thing to the internet – what they were calling Fest In Place – Nordell explained that their first move was to get everyone on the same page and figure out how it was going to work. The board, including Festival Director Lisa Schwartz, brought in Jerry Rivers, technology expert at Folk Alliance International in Kansas City, and Sam Bolenbaugh from Mountain View Staging, which ended up doing the digital hosting of all the weekend’s streams. According to Nordell, “Everybody came together to make sure that this event could be pulled off and could be executed well.”

Asked if this was a reinvention of the Folk Fest, Nordell replied: “It’s a continuation of everything we’ve ever done, I feel very strongly that we worked incredibly hard to capture as much of the festival experience as we could digitally. … The hope was that we would be able to move the festival into the 21st century in a way that we’d only dreamed of, but we never had the kick in the pants to do it. And frankly, [we] would never have done it if it weren’t for COVID-19.”

At the core of the Philadelphia Folk Fest is the army of volunteers that keep it running smoothly year after year. Unlike other festivals of similar size and history, the thousands of volunteers on Old Pool Farm are omnipresent when it comes to everything from parking to security to hospitality to archiving and really everything else. While much of that obviously does not translate to a livestream, help was still needed, especially when it came to making sure the event ran smoothly. Enter Matt Diamondstone, who historically has volunteered with the merchandise committee. This year his job was tech support.

While Folk Festers are a dedicated and resilient bunch – ask anyone who has camped even just once and they will regal you with stories about storms, mud, gross Porta Potties, obnoxious hippies, and everything else that makes the Fest the Fest – hooking up a laptop to your TV is a lot different than pitching a tent. That the help section of the website was staffed not just by real people but by actual Folk Fest volunteers was very important to the Folksong Society.

“We assisted over 2,000 people during the festival, helping folks log in, see the music, broadcast it to their TV, and all manner of other technical challenges that come with a digital festival,” Diamondstone told The Key. Volunteering is an integral part of the Folk Fest experience for him and he explained that “the community of people who are willing to spend so much time and energy to make this happen is unparalleled in any other facet of my life. It was a great to have the privilege of speaking with so many folkies during this year’s festival – it made it feel more like the Fest I know and love.”

There were 169 performances at the 2020 festival. With very few exceptions they were almost all either live or pre-recorded specifically for the event. It was, like every Folk Fest, a mix of the famous – Los Lobos, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Richard Thompson, Ben Gibbard – and the hitherto unknown, from across a multitude of genres and generations. While all the musicians were offered payment, Nordell said that some of them refused and asked for the money to be donated back to the Folksong Society which, outside of booking shows, also does a lot of youth music education programming in the Philadelphia region.

The organization partnered with a number of groups from around the world to provide some of the programming, including Culture Ireland, the National Arts Centre Canada, Showcase Scotland Expo, Home Routes / Chemin Chez Nous (Canada), SORI (South Korea), and Wales Arts International. There was also the ability to dip into the vast archives of past festivals going back decades, something that the public has never had access to before. This was a huge draw.

Rob Malerman is a longtime festival goer who normally volunteers with the Communications committee. On Facebook he wrote, “I think the archives are my favorite part. I never seem to have much time for the music. It is great to relive some of the high points and catch up on what I missed.” That sentiment was echoed by many people on both social media and the Zoom-based ‘campsites’ set up by all the different groups that make the festival grounds home every year.

Nordell referred to the archives as an “incredible piece” of the Folk Festival that’s been “so difficult to really wrap our arms around” because of just how much historical documentation exists. In 2015 the Historical Society of Pennsylvania assessed the whole collection – video, audio, and printed materials – and discovered that “we had in our possession one fifth of the known musical archives of the City of Philadelphia” according to Nordell.

But up until this past weekend, almost nobody had seen any of it, including Nordell, who joked that “People think that I’m sitting in my office watching David Crosby all day.” That’s partially due to much of it not having been digitized before but mostly because of licensing issues. To make that work for the festival they had to sit down with a multitude of lawyers and artist representatives to hammer out an agreement. Much of the work on getting the videos online was done by Phil Nicolo, a Grammy Award-winning producer who volunteers with the Production committee, and Bolenbaugh from Mountain View Staging.

The assistant chairperson of the Archives committee is Trish Hurley Callahan, who has been coming to Folk Fest since 1972 and started to help document things in 1974. She was profiled in The Key as part of an article about Folk Fest volunteers two years ago. For her the archives part of this year’s festival were, “the most amazing two weeks of memories and going back in time during a time when, you know, we don’t have that much else to do. We’re quarantined, we’re isolated, we’re not going on vacations. But this was like a total vacation into our into our memory bank.”

The archives were also a great way for those who might not have as long a history with the festival to dig deep into its past. The videos stretch from the 22nd festival in 1983 to today and include sets from all manner of musical luminaries and fest favorites. There are very few concert series that can claim Doc Watson, Utah Phillips, Huun-Huur-Tu, Iron and Wine, and Queen Ida. And that’s just since 1983! While the videos are only available during the festival – ticket holders have until the 24th of this month – the Folksong Society announced plans to make them a regular feature of future fests.

Although it was a lot different than watching bands play in-person, the livestreaming and archives add a level of accessibility that is not usually a part of large festivals like this. According to Nordell, “For the first time ever, this event is fully accessible to everyone and anyone. There are no limitations on it other than technology, but even then we’ve helped some of our volunteers get access to both internet and technology to watch the event.” He said that once the pandemic has ended and regular concerts return that everything the Folksong Society does will be streamed online, too. “We just want to make sure that the future of this event, of this organization, will be able to be accessible,” he told The Key. “So people will be able to watch the physical festival from the Old Pool Farm in Upper Salford Township [or] from the safety and comfort of their own home if they don’t think they can make it out.”

This year’s festival was viewed from across the country and across the world, according to Nordell. While regular fest goers will make it a point to come back every year no matter where they might live – as he put it, “it’s very rare that people come to the Philadelphia Folk Festival just once” – that’s not always an option. Add in the fact that camping for days in the inevitable muddy mess of the grounds can be challenging for the most able-bodied young people and it makes sense that they’d want to expand the fest online.

While it’s impossible to replicate the atmosphere and environment of the Philadelphia Folk Festival, many of those viewing from home got together to celebrate either in-person or just virtually. Callahan told The Key that she joined other members of her regular campsite, called The Talentsuckers, following a two week self-quarantine period and with safety protocols in place. “We put up our tents and we put up all of the flags and the banners,” she said. “There was a food tent, there was a beer tent, there was a performer hospitality area. There was volunteer check-in when you got there. There were signs on the road that said ‘Folk Festival’ leading to the driveway. It was great.”

One of the 169 performers at this year’s festival was Philadelphia’s own Emily Drinker and her band. Drinker has been coming to the fest since she was a kid, has played there numerous times, and even worked for the Folksong Society for a while. While this year’s event was a lot different than any other one, she told The Key that “I didn’t hesitate to accept the offer to perform for Fest In Place, as it meant that I’d be sharing a bill with some of my all-time favorite artists (Allen Stone, holy wow) and participating in this long-standing tradition about which I am so very passionate.”

In the days leading up to the festival Drinker said she spent a lot of time looking through old pictures and reflecting on the more than a dozen years she’s been attending. The yearly event has played an important part of her life and even if 2020 was virtual it was still Folk Fest. As she put it, “We needed Fest, even if it wasn’t the Fest that we are all used to. We needed to remember and celebrate the life of one of the Festival’s founders, Gene Shay, whom we lost to COVID-19, as well as the would-have-been headliner, John Prine, also lost to the virus.”

Drinker and her band recorded their set in a friend’s backyard in Bryn Mawr. While she has been doing a number of livestreamed concerts over the past few months, this was the first time she had been able to play with the full band.

Although nobody who participated in the 2020 Philadelphia Folk Festival would describe it as ideal, it very much was that considering everything the organizers went through to put it together as well as the quarantine environment that we find ourselves in these days. “Going forward, I think we have hit a new age – we’re going to be able to stream the stages next year in concurrency with the in-person festival and bring not only our music but our vibrant folk community to a wider audience,” Diamondstone said.

For Callahan the experience “was just incredible.” From the performances to the archives, the memorials for Shay and Prine, and the online campsites, it was all “totally interactive and very, very intimate,” she told The Key.

While nobody wants another Fest In Place – Drinker referred to it as “the first and hopefully last virtual Fest” – this was an accomplishment. Asked what he was most excited for at next year’s festival, the 60th, Nordell said: “More than anything I’m looking forward to being able to safely be around my Fest family, the people that I love. Being able to hopefully maybe give hugs or whatever the 2021 version of a hug will be and being able to enjoy live music.”