Shamir comes into their own on introspective and category-defying self-titled LP

Many factors point to why Shamir Bailey’s new record sets itself apart from their other work. Shamir’s self-titled LP is their 7th studio album and second this year, following the distorted rock Cataclysm. Self-titled projects usually occur as debuts or early-career capsules designating an artist finding their sound. This wasn’t the case for Shamir, as their catalog of projects has experimented with multitudes of sounds and approaches to music, leading to the product that feels most like their authentic self.

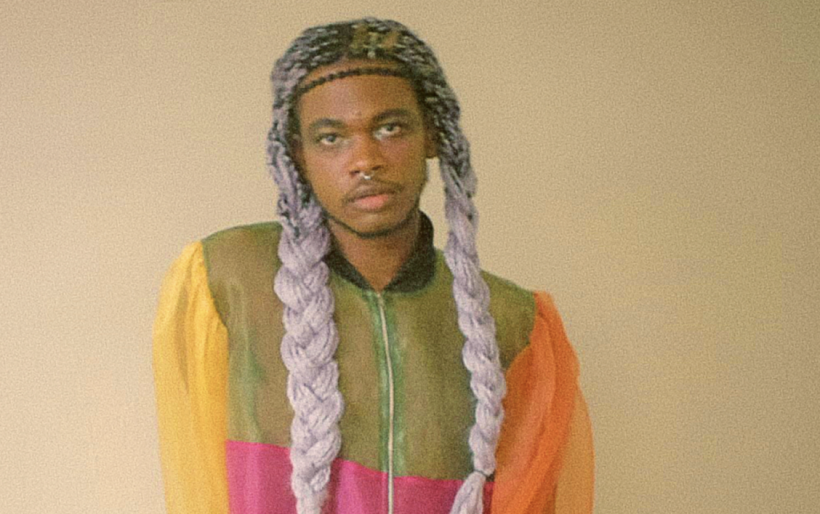

Shamir has been pictured on all of their album art, but the non-musical symbolism that speaks to the record’s personal significance exists in the artwork. It is fairly simple, with Shamir seated in front of a wall that could be found in the average home, but it is the first time they’ve appeared without distorted facial features or hidden behind a black and white filter. Instead, Shamir is fully visible, adorned in beautiful colors of their purple hair and tulle green, yellow and orange jacket. The jacket, too, has a story itself: Shamir explained on Twitter that they got it from a thrift store in Manhattan and saw it a few weeks afterward worn by a dead trans sex worker on an episode of Law and Order SVU. Shamir wanted to immortalize the jacket in a positive light on the cover because the representation in the episode was brief and tragic, something typical to trans storylines.

It feels almost pointless to mention “On The Regular,” a track that Shamir has long been tied to, because the work they make is so distant from it. But that is exactly the point. The Shamir we see now is seasoned, having jumped around different genres, and with six self-released projects under their belt, Shamir’s newest is unrecognizable from the track people tend to connect them to. It transcends all genres and defies categories, but that does not make the album less holistic, as its departure from a single mold is encompassed by the artist’s energy and introspective, personal delivery.

“On My Own,” the power-pop opener, is a declaration of self-resourcefulness, rejecting the feeling of needing someone to make you feel self-worth. The looped guitar at the beginning of the pop-rock “Running” feels like the repetitive motions of a jog, and the clarity in Shamir’s vocals speaks to the song’s message of showing up as your whole self and leaving people who make you dull yourself down. On the country-infused “Otherside,” Shamir takes on a different songwriting approach, something seen on Taylor Swift’s Folklore, of writing from the perspective of someone else, like taking on a different character. “Otherside” was inspired by an episode of Unsolved Mysteries, where a woman’s husband died during the Vietnam war, and she wanted more answers about his death. Shamir’s voice accompanied by a banjo is certainly not common but their vocals beautifully float over the instrumentals and take on a powerfully rough vocal progression in the chorus.

The overarching theme of vulnerability exists through reclamation but is also cast in different lights as Shamir delves into its different forms. On the rock-esque “Paranoia,” a distorted guitar riff is the backdrop for a track that features a self-explorative Shamir, where they discuss the paranoia they experience, “But paranoia seems to be my very best friend / I wish he’d go away I never want to see him again.” Personifying paranoia seems indicative of its power, as oftentimes mental health-related issues are so apparent that it feels like their power can only be implemented by a person, which ultimately is the truth because it exists within the person experiencing it. But Shamir’s acknowledgment of paranoia’s role seeks strength through vulnerability.

The garage-pop song “Pretty When I’m Sad” and soft-rock-meets-electronic “I Wonder” both speak to relationships, a combination of feeling like a burden, acknowledging flaws in both people, and taking on pain for the sake of security in someone else. The album closer is a dark, theatrical-like track filled with strings and a highly emotive Shamir. They reflect on happiness coming with age and seeking it as a constant feeling rather than viewing it as fleeting.

Shamir is short, just shy of 30 minutes in length and 11 tracks long, three of which are 15-second interludes. But its brevity can’t really be felt, as the listening experience is intimate and its effects are lasting. The confessional lyrics sprawled across an array of sounds connect listeners to Shamir in a way that hasn’t been done before, and their visceral lyrics navigate topics that may resonate beyond perceiving them as only belonging to them. Shamir is a beautiful collection of unguarded emotions that withdraw from the pressures to conform.

Listen to Shamir below.