Inside one folk song, (popular music as well, thanks to technology) you can meet a people, their linguistic tradition, the types of melodies and rhythms that make them tap their feet, and some of the everyday realities of their culture. The words “God’s gonna set this world on fire one of these days, hallelujah” reveal multiple truths about the enslaved Africans in America who sang this traditional song. There is a spiritual truth, a belief in a metaphysical existence on the other side of this reality where enslaved people will be able to “sit at the welcome table,” and “eat and never be hungry.” It reveals a political truth, a dissatisfaction with the conditions they were forced into, and a hope for a reckoning for the world that created those conditions. Just one round of this spiritual, if you’re truly listening, can teach you so much about being Black in America.

I love the way one of my favorite podcast hosts, Combat Jack (may he rest in peace), broke down the difference between Cali and New York Hip Hop of the early 90’s on an episode of Gimlet Media’s Mogul. Cali hip hop, he said, hits best while driving in your car on a warm sunny day, a smooth beat to vibe to with the windows down. Whereas in New York, they were rapping to beats fit for a person riding the subway all day with their boombox.

But this is 2021 where a kid in Philly could listen to nothing but K-Pop if they so choose, cultural specificities become less and less obvious in one song in such a globalized world. However, one song can still teach you these same things about the individuals who created them.

One listen to one of my songs could reveal to you that I am a child of a woman from the north of Haiti, where it’s more common to find women playing instruments than in the capital. You’ll find that I play a guitar with nylon strings because Haitians tend to finger pick more than they strum. You might glean from the vocal stylistic choices I make that I’ve spent most of my life in Philly listening to gospel, obsessed with Lauryn Hill, imitating Brandy’s ad libs. You might realize my dedication to keeping my mother tongue strong and present in my art because I worry about losing pieces of my culture as an immigrant in Philadelphia. You’ll find that like any other millennial, I’m seeking answers and explanations for the conditions of a world that I am dissatisfied with. But most importantly, you’ll find that I love Haiti.

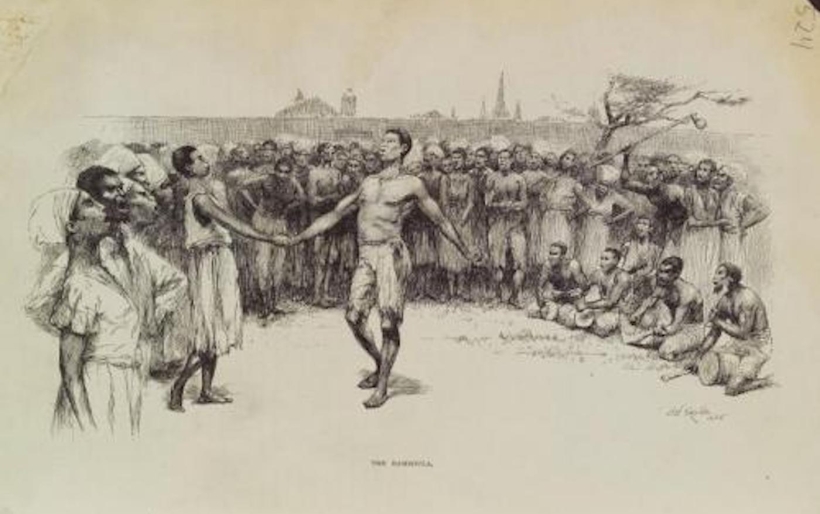

As far as oral tradition goes, the tradition of song holds so much. It’s no wonder that certain founders of western music education philosophy were of the mind that folk song is where a child’s musical education should begin, the songs that feel most intrinsically like home for the child. The connection between Haiti and New Orleans might be long forgotten in the consciousness of the people in these respective places, but the shared themes of displacement and life under colonialism in the words of the folk songs, as well as the syncopated dance rhythms of the drums of the Bamboula live to tell the tale. After all, as the classic Haitian song by Septentrional says, tanbou frape Ayisyen kontan–the drum hits, Haiti rejoices. And apparently, so does New Orleans.