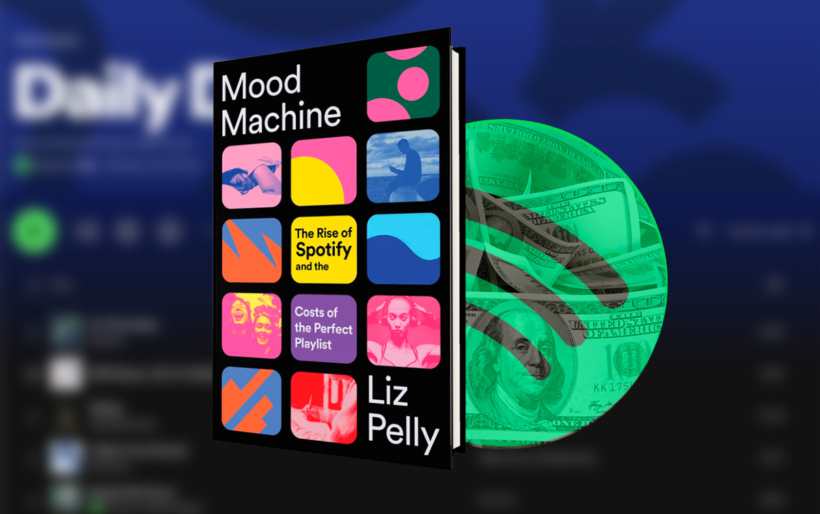

It’s no secret that Spotify and other streaming services have changed the way listeners access music and the way musicians earn an income. With more than 675 million active users, Spotify leads the industry and promotes itself as a platform “giving a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their art.” But not everyone sees it that way. Journalist Liz Pelly has long scrutinized Spotify’s unchecked influence, and in her new book, Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist, she explores the platform’s broader impact. From shrinking artist royalties to the suspicious use of AI in music generation, Pelly lays out a case for concern.

Earlier this year, Pelly stopped by Lot 49 Books in Fishtown to discuss Mood Machine with Speedy Ortiz’s Sadie Dupuis. In both the talk and the book, Pelly examines how streaming platforms like Spotify often benefit executives more than artists — CEO Daniel Ek, for instance, is now wealthier than any musician in history. The FAQ below pulls from that conversation to help artists and fans navigate the ethics of streaming music on Spotify.

Should I be worried that Spotify is collecting so much of my data?

Like so many apps on your phone, Spotify is recording your data. “If we know the basics of surveillance capitalism,” Pelly said in chat with Sadie Dupuis, “we know that every click, every playlist you make…every move on this platform is being recorded and logged in a folder of data somewhere.” So what can Spotify do with that data specifically? Pelly suggests we should be skeptical of dystopian-sounding reports of how Spotify can metaphorically read your mind. “There’s a lot of things that seem really spooky,” Pelly admits. But she continues, “companies are sort of overhyping their own abilities in order to draw in investors.”

While it’s worth speculating what Spotify will be capable of in the not-so-distant future, you should know how they’re treating your data presently. With the billions of data points Spotify collects from your listening, they can make inferences that range from relatively harmless, like info that comprises your “Spotify Wrapped” and music recommendations, to invasive, like targeted advertisements, and selling this data to data brokers. “Maybe it turns out Spotify shares the information with a data broker, which is, in turn, absolutely happy to share this information with another actor to make a very detailed profile about me,” shared Stefano Rossetti, a data protection lawyer with the Austria-based privacy organization None Of Your Business, in Mood Machine. This “ID syncing” as it’s known, compiles your data from various sources, and uses it to target you for advertising, political messaging and more by selling your information to various interests.

Are Spotify playlists contributing to the further homogenization of music?

The popular playlists on Spotify themselves are cultivating an identity, and dictating the music that fits, instead of the other way around. We see this in the example of PFC, where music is commissioned to fill the playlists, scoring the background music of our lives, with little concern for the artists who created it. In Mood Machine, Pelly lays out how this phenomenon has specifically affected two scenes in music: hyperpop and lo-fi hip hop beats. Both genres started with real communities of artists, inspired by producer techniques and experimentation, and often represented voices of BIPOC and queer individuals. But as playlist culture evolves, those communities are “subsumed under this curatorial project,” Pelly notes, with increasing contributions from AI.

“The streaming playlist ecosystem started to tell people in that scene what they were like in a way. There’s a lot of people trying to like, make this music because they see these specific types of sounds doing really well on playlists. So it’s incentivizing people to now just specifically make this type of music.” Pelly mentions Safiya Umoja Noble’s theory Algorithms of Oppression when talking about this “playlistification,” showing that private interests of monopolies privilege conformity, whiteness, and patriarchy. In other words, they contribute to ongoing social problems because they echo the same biases held by the people and systems that shape them. “And then people who were originally part of a scene, get disgusted by it, and don’t wanna be part of it anymore. They’re like, don’t use that word [lo-fi hip hop beats] to describe me.”

How much music on Spotify these days is made by AI?

Rumors have been circulating for years about how a growing number of artists on Spotify aren’t, well, human. While AI cannot at this time cannot write its own music, it can analyze patterns and structure of existing music, creating its own compositions. In Mood Machine, Pelly admits she was not interested in the narrative that programmers were using AI to compose music to platform on Spotify – she says it distracts from the larger grift: Spotify profiting off the labor of artists on their site.

In 2017, a new development in AI music on Spotify turned Pelly’s head. That year, the internal program PFC, or Perfect Fit Content, was created to commission music for Spotify playlists. “I learned that [AI involvement] wasn’t actually DIY hustlers gaming the system, but actually an internal program at Spotify,” Pelly told us at Lot 49 Books. So, independent musicians or AI alone aren’t writing junk music to fill playlists; rather, Spotify is commissioning musicians (who may involve AI) to produce trending music at a discount rate.

According to Pelley, the initiative is essentially “a scheme to lower royalty costs” by filling popular playlists with inexpensive, easy-to-produce tracks. These songs are often made in bulk by anonymous producers using pseudonyms. A former Spotify employee told Pelley they didn’t know who was making the music or where it came from – only that the company made money from it. As Pelley put it at Lot 49 Books, “It’s a lot easier for streaming services to, you know, deal with artists who ‘don’t exist.’”

I’m an independent artist having trouble pitching to playlists. Why is it so difficult to break through?

To understand why it’s not easy to stand out on Spotify as an independent artist is to know how Spotify is built. First and foremost, it’s a profit-driven platform that relies on user participation. The app is designed to be addictive, says Pelly, and its algorithms and playlists are meant to keep you lulled into using the app for long periods of time. A large part of how Spotify makes its money is through deals with the major labels, who lower their royalty rates for artists in favor of preferred placement on the app. Essentially, they’re trading the artists’ pay for a spot on your “Discover Weekly,” for example. Throughout Mood Machine’s 16th chapter, she likens Spotify’s “pay-for-play arrangement” to the outlawed radio payola of the 1950s.

These barriers make it hard for independent artists to make a splash on Spotify, and dashes the narrative that “streaming is a data-driven meritocracy, and the music that becomes popular is because it’s the best.” Therefore, even at $0.0035 per stream in royalties, an independent artist is not profitable enough to receive preferential treatment from Spotify.

If Spotify and their playlists have so much power in the industry, is it unwise for emerging artists to speak out?

Pelly has sympathy for artists playing the “promo game,” and for the listeners who use streaming services regularly because “the musicians and the listeners aren’t the people making these corporate policies.” Though she never says that deleting our apps is the answer, she does acknowledge that having a community is more valuable than playing Spotify’s games. “Organizing and realizing the power of having a collective voice is worth a lot more than like, a small amount of royalties you might miss out on from not being on, you know, ‘Fresh Finds: Indie,’ or whatever,” Pelly told Dupuis and the audience at Lot 49 Books.

A productive place for your criticisms of Spotify and the streaming industry is with UMAW, the United Musicians and Allied Workers coalition, and there’s a chapter here in Philly (which Dupius is a charter member of). Nationally, UMAW successfully negotiated for transparency of our streaming data (which you can download from the Spotify app via Account, Account Privacy, Download Your Data), and is working toward more reform of the industry. Follow UMAW Philly on Instagram to see when they’re meeting next.

As a music streaming platform, Spotify and its CEO Daniel Ek must have a fondness for music, right?

Though we can’t deny Ek has indeed enjoyed listening to music in his life, that wasn’t the driving force behind Spotify’s creation. Originally, Pelly describes, Spotify was designed in early Y2K as an advertising product, and adapted music as its traffic source for its low file size compared to video, and relative accessibility. Ek would later encounter many legal entanglements gaining licensing from the major record labels, but at Spotify’s beginning, piracy was rampant on the internet, so much so that Sweden was considered “a lost market” in the industry. Pelly describes how “desperate the private and public spheres alike were for something that would ‘solve’ piracy.” In fact, the first tracks to populate the platform were “culled from [employees’] personal music libraries, including many downloaded from the Pirate Bay,” the popular peer-to-peer sharing BitTorrent website.

I’d like to see music listening not so closely tied to big tech. How do we move toward that future?

It’s reasonable to, after all this information, still return to Spotify to listen to music. In Mood Machine, Pelly points to the ubiquity of streaming, and doesn’t shame artists or listeners for using the app. Though, “it’s never good to be totally wrapped up in any single, corporate-owned tech company,” she said at Lot 49 Books. Bandcamp is one, albeit flawed, alternative. But perhaps most exciting are the cooperative solutions proposed by artists themselves.

In Chicago, Pelly spoke to a group of musicians who designed their own streaming platform, Catalytic Sound. “Designed to help create economic sustainability for its artists through patron support,” Catalytic Sound hosts 33 artists who all share a subscription fee to their music, and receive half of their album sales directly. “It’s a way of rethinking the technology of streaming with a different business model that gets away from the per-stream valuation of music,” says Pelly. With government regulation of the streaming giants becoming less and less of a viable option, new artist-managed technology is an attractive solution. Later that night at Lot 49, after Dupuis asked, “C’mon, I know someone here is a coder!”, we all quietly glanced around the room.