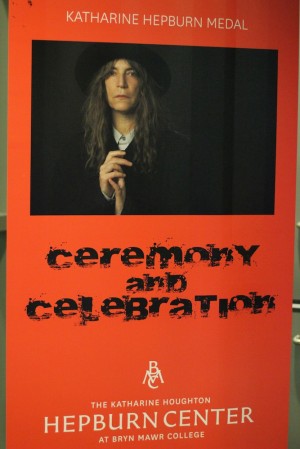

Punk legend Patti Smith recieves the Hepburn Medal at Bryn Mawr College

Patti Smith | Photo by Chris Sikich | countfeed.tumblr.com

Most colleges consign punk rock to dorm rooms, obscure airwaves or an out-of-the-way venue. Maybe even a class or two. But when it comes to the top brass, not too many pledge allegiance to the punk flag. Then again, not too many Main Line schools get to salute a legend like Patti Smith.

“I suspect Bryn Mawr actually has a punk spirit,” college President Jane McAuliffe said Thursday night before presenting Patti Smith with the Katharine Hepburn Medal.

Photo by Chris Sikich | countfeed.tumblr.com

Kim Masters of The Hollywood Reporter, the night’s master of ceremonies, pointed to actress Katharine Hepburn and her mother, family-planning advocate Katharine Houghton Hepburn — both Bryn Mawr graduates — as “trailblazing women who defied convention.”

And while that description also fits Patti Smith, she’s not necessarily the first candidate you’d come up with for the Katharine Hepburn Medal, which was first awarded in 2006 to recognize achievement in film and theater, women’s health and civic engagement. The previous winners — actresses Lauren Bacall and Blythe Danner, mural maven Jane Golden and HIV expert Helene Gayle — fit more neatly into the medal’s mission.

But Smith’s CV is anything but neat; you’ll run out of hyphens before she runs out of energy. She’s a rocker-memoirist-photographer-actress-model-playwright-muse-critic-painter-poet — and you know I’m forgetting something. Not bad for a South Jersey girl who dropped out of Glassboro State College to be somebody in New York City.

In a brisk but heartwarming event, woman after woman paid tribute to Smith.

Michaela Majoun and Patti Smith | Photo by Chris Sikich | countfeed.tumblr.com

XPN’s Michaela Majoun noted that Smith managed to have it all, though by retreating from public life for most of the ‘80s and ‘90s to be a wife and mother, Smith didn’t follow the path that fans and feminists would expected from the fiery performer who breathed new life into rock with 1975’s Horses and the albums that followed.

“Her music upended rock itself,” said McAuliffe. The college president took notice of Smith’s cross-generational appeal, which drew alumnae from the ‘60s and beyond, including students and parents.

Katherine Rowe marveled at Smith’s “diverse modes of expression to amplify her voice,” but in her role as director of Bryn Mawr’s Katharine Houghton Hepburn Center, she sees the next generation of women with too much ambition and talent to be tied to any one field.

“If you obey all the rules, you miss all the fun,” Hepburn once quipped. And in picking this year’s medal recipient, Rowe said, the question was: “Who has broken the rules in ways that really matter?”

Patti Smith | Photo by Chris Sikich | countfeed.tumblr.com

Patti Smith, that’s who.

In accepting the Hepburn Medal, Smith shared two impressions of its namesake.

First she spoke of watching the 1933 film adaption of Little Women, which starred Hepburn as the fiercely independent Jo March, and feeling that the actress did justice to the stubborn, generous, awkward tomboy that had made Smith (and so many other girls) dream of being a writer.

Then she recalled working at Scribner’s bookstore soon after landing in New York, and helping Hepburn find books. “I think Spence would like that,” the actress noted of a book that reminded her of her late love, Spencer Tracy. Years later, Smith said, she thought of that exchange when she was newly widowed. Hepburn gave her the courage and permission to shop for Fred “Sonic” Smith, at least mentally, after he was gone.

With the great web of humanity on her mind, Smith spoke of her generation looking up to Hepburn, and of meeting with the current crop of students Thursday afternoon. (“They seem like a great bunch.”) And so the torch is passed and passed again.

After reading the last letter she wrote to longtime friend Robert Mapplethorpe, the focus of her acclaimed book Just Kids, Smith observed that the S&M photographer and the Oscar winner had both nourished her youth and guided her through her midlife grief.

She played one song, “In My Blakean Year,” from 2004’s Trampin’, as a benediction for students embarking on lives that will be scarred by strife and sacrifice. “The reward is in doing our work well,” she said. And though the song is determined and somber, she couldn’t help but smile as she performed.

As she finished, she seemed to have one last thing she wanted to say. But McAuliffe presented Smith with her medal, whisked her away, and it was time for dessert.