The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller: Talking soundtracks and ephemera with director Sam Green and Yo La Tengo

For 15 years now, NYC and San Francisco-based director Sam Green has been making documentary films, enlightening audiences about domestic radicals, exile, language, and more. For his latest project, The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller, he explores the life and work of Buckminster Fuller, with a little help from indie rock vets Yo La Tengo, who accompany his live narration with an original score.

Since debuting in 2012, the project has hit 10 cities, and will journey to Philly’s FringeArts this Friday. In advance of the show, I rang up Green and YLT’s Ira Kaplan—to talk songwriting, ephemera, and why Buckminster Fuller.

“His philosophy is in the air these days,” says Green, with a laugh, of Fuller. “He was pretty obscure for a while, but he’s back, as they say.” A mid-twentieth century philosopher who advocated sustainability, efficiency, and using design to solve real-world problems, Fuller is perhaps best known for inventing the geodesic dome, although his contributions to math, science, and urban studies are varied and great.

“He was a Batman character, a larger-than-life character, a very rich persona,” continues Green. “He was wildly optimistic, and a visionary. I put myself in that group as well.”

Green first encountered Fuller’s ideas while working on a project for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art—“they were running an exhibit about Fuller, and asked me to do a documentary,” he says. As he dug deeper into Fuller’s life, he became intrigued.

Green’s previous work, Utopia in Four Movements (a multi-episode oeuvre tackling China’s largest shopping mall, the rise of Esperanto, and more), used a live documentary format, in which Green narrated video clips and was accompanied by a live band. He decided to use the same format for Fuller.

“I was thinking: who would I love to do music for this? Who has the right sound?” He continues. “I’ve been a big Yo La Tengo fan for many years, and I had seen them do a similar show, where they played live music to movies, once before. So I got in touch with them, and they were up for it.”

“Sam came very highly recommended,” says Kaplan with a laugh, who was introduced to Green through a mutual friend. “I wasn’t too familiar with Fuller’s philosophies beforehand, but it’s far from required that you know about him to enjoy the show. This is not a dry academic performance.”

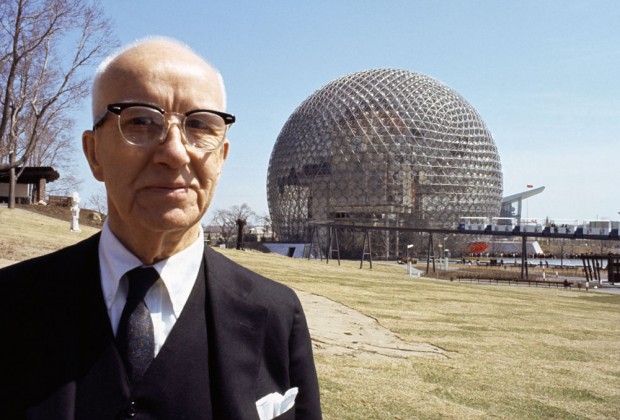

Buckminster Fuller, alongside his famed geodesic dome

Fans of Yo La Tengo are likely familiar with the band’s previous soundtrack work, which includes 2005’s Junebug and Game 6, and 2006’s Shortbus and Old Joy, in addition to the well-known The Sounds of the Sounds of Science, a 78-minute score set to eight underwater films.

At this point in their career, Yo La Tengo are practically pros at writing scores. Yet they also admit the process comes with its own unique challenges.

“As we’ve demonstrated with the songs we’ve written for ourselves… a song can be whatever length we want it to be,” says Kaplan, referring, perhaps, to the 7-minute opener to 2013’s Fade. “In a soundtrack situation, it’s not like that. They’ll have a clip that’s 34 seconds long, and they’ll need 34 seconds of music… and if you write 43 seconds, it’s wrong.” He pauses.

“Each one of these projects is of course different from every other one,” he continues, “The Sounds of Science being the most different because there was no filmmaker involved.” (The filmographer, Jean Painlevé, had passed away). “With that, we had the freedom to do whatever we wanted. Everything else we do, the director is the ultimate decider.”

So what was it like working with Green?

“Sam was probably more involved with this project than most, primarily because of the schedule we were on,” he adds, explaining that in the past, the band would compose music independently, then send it off to the director electronically—but that time constrains did not allow for such a process with Fuller. “It was done quickly to the point where we just invited Sam to come to our rehearsal space and join us while we were writing,” he adds.

The face-to-face sessions resulted in a more intense process for both parties—but ultimately yielded great results.

“It was really interesting to see them work,” says Green. “It was fun. Usually with films like this, it’s entirely the director making decisions. So this was odd and sort of exciting because it was more of a collaboration. I was a little starstruck at first, but they’re just regular people. We had a good time.”

“It was tricky having Sam in the room; we’re not used to it,” admits Kaplan. “He was reacting instantly, and we were responding instantly, which was putting a lot of pressure on everyone. But it created a nice challenge. And obviously we’re still speaking to each other so it worked out.” He laughs.

Yo La Tengo accompanying Green live (Photo by Ed Dittenhoefer for The Ithaca Times)

Preparing the piece for performance of course was only one challenge—once it was complete, the team faced another large undertaking: figuring out how to bring the massive production on the road.

“The flipside to creating a piece like this, that’s only performed live, is that you gotta go across the country and actually DO this,” says Green, who in the past has taken works across the continent, and to Europe. “But I don’t mind. I love it actually. You have to put in a lot of energy to make it work. Those challenges are not negative.”

Kaplan agrees. “After doing the Painlevé, we didn’t think we’ve ever do another project like this again, just because it’s a large show for us to mount. But this is not our show, so it’s faster to set up, and we’re a little lighter on our feet with it. It’s different—but that’s one of the things we like about it.”

A past performance of Fuller (Photo by Charlie Villyard)

So what’s the greatest challenge Green and Kaplan have faced, now two years into the project?

For Green, it’s questions of transience, and appreciating a project in a temporal state.

“Sometimes people will stay after the shows to do a Q+A, and they will say things like, ‘Wouldn’t it be easier to turn this into a DVD?’” He pauses. “If you’re a filmmaker now, lots of people are watching your stuff on their phone, while they’re also watching TV, or doing something else. People watch movies in very diminished ways these days. So it’s nice to capture the magic of cinema. One of the things I like about this project is that it’s ephemeral; you’re never going to stream it on Netflix or watch it on Youtube—it can only happen live.”

Kaplan agrees. “One of the reasons this is being done this way is because these days everything is online; everything is accessible—and there’s something we all like about something that is NOT accessible. You actually have to go to see it.”

“I think we’ve gotten better and better,” says Green, reflecting on their progress thus far. “That’s one of the things I’ve been struck by lately. We did some shows last fall and they were all like, our best shows ever. … We’re just hitting our stride with the piece now. It finally feels like everything is clicking.”

We’re psyched to be a part of the magic.

The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller comes to FringeArts, 140 N. Columbus Blvd., this Friday, April 4, for two performances: at 7:00 and 9:00. Both performances are sold out.