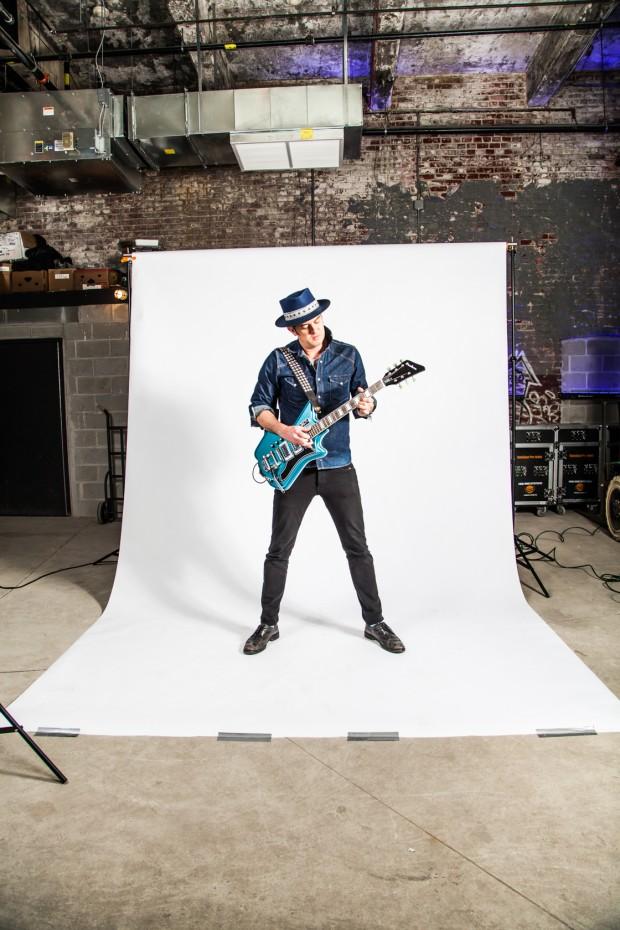

G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

The High Key Portrait Series: G. Love

“High Key” is a series of profiles conceived with the intent to tell the story of Philly’s diverse musical legacy by spotlighting individual artists in portrait photography, as well as with an interview focusing on the artist’s experience living, creating, and performing in this city. “High Key” will be featured in biweekly installments, as the series seeks to spotlight artists both individually and within the context of his or her respective group or artistic collective.

We seem to be enjoying a bit of a 90s renaissance lately. A bill full of 90s headliners sold out The Fillmore in Philadelphia two weeks ago, and last week another Clinton addressed a Philly-hosted national convention. An “I Love The 90’s” Festival featuring Salt-n-Pepa, Vanilla Ice and Color Me Badd hit BB&T last week. The revival is afoot.

Most of Philly’s Gen X-ers will remember that era of the city’s cultural history with a special reverie, and listening to Garrett Dutton reflect on those years in anecdotes is sure to evoke nostalgia for anyone who was there.

In a candid interview held backstage at his Fillmore show earlier this year, the man known as G. Love talks sentimentally about his days tagging walls and playing street corners and cafes, about basketball and the neighborhoods he called home. He recounts first recognizing the potential of integrating elements of blues rock and hip hop to develop his signature sound. He doesn’t pull punches, either, about the frustrations he faced as a recording artist, with open rebuke for the elements of media or local industry that from his perspective offered paltry support.

While Dutton is known best for the hits that drove his early following, his latest records and performances show an artist still evolving. Last October, G. Love and Special Sauce released their latest record Love Saves The Day, a collection of blues rock tracks including collaborations with the likes of Lucinda Williams and Los Lobos vocalist David Hidalgo.

Speaking of that 90s revival, though, mark your calendars: G. Love plays the Mann with Blues Traveler and The Wallflowers on August 21st. Tickets and more information on that show can be found at the XPN Concert Calendar.

G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

The Key: You’re Philly born and raised?

G. Love: Yup, I was born in Pennsylvania Hospital, and then I grew up downtown, like 2nd and Pine.

TK: You went to high school at Germantown Friends. What are the first memories that come to mind when you think back on that time?

GL: My high school was pretty cool, ‘cause there was a lotta Philly musicians that came outta GFS. Eric Bazilian from the Hooters went there, Santigold went there — Santi was two years behind me, I remember we were good buddies. And then later there was a kid Alec Ounsworth, from Clap Your Hands Say Yeah. So it was a pretty creative school, and I think it kinda just taught people how to think outside the box a little bit. In high school we started playin’ out on the street, in Headhouse Square, my friend Eliza Dictor and I — she played saxophone — and then also my buddy David Katowitz, “the Kat Man,” we played out on the street a lot. My first big show was the high school talent show in 10th grade. That was when I really got hooked on bein’ on stage, you know? That must’ve been 1989.

TK: How do you remember first getting connected to the Philly music scene?

GL: In high school I started playin’ out on the street — I played South Street, and 2nd and Lombard. And then I had a couple early, early acoustic coffee shop gigs. There was this place McCann’s Kitchen — I don’t think it’s there anymore, it was up on like 20th and Spruce. And then I would go to the open mic nights at the Sam Adams Brew Pub, I remember going to open mic night at The Barbary, but I was just getting my feet wet. And then around the time I moved to Boston, which was ‘92 — that was maybe the first summer that The Goats started — played on the streets there. And then I found my band in ‘93, and then we got invited to play at the Philadelphia Music Conference, so I actually kinda got discovered out of Philly, so we started comin’ back down here. And our first gig here was playin’ with The Roots at The Revival, part of the Philadelphia Music Conference. That was cool show for me, ‘cause like, Chuck Treece showed up, and The Goats were all there.

And then I remember the first time I met The Roots like, they were in the lounge of Studio 4, and we were startin’ to work on a new record. And Tariq and I are good buddies now, but then he wouldn’t even shake my hand. Shit was not as open back then, especially in the hip hop world. They were like, ‘yeah whatever, white boys.’ But obviously they did good. Our first gigs in Philly were like the Khyber, and Dobbs — we had a pretty classic gig opening for The Goats at Dobbs, you know doin’ our own headline — mostly those places, and then The North Star Bar, and TLA, and Factory, and you know, Penn’s Landing, and Tweeter Center…

G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

TK: Since you mentioned this, I know that a lot of your music is derived from Black culture — blues and hip-hop. I remember reading in the Roots’ liner notes for Things Fall Apart where they sort of lament the idea that their audience was largely white, or how Eric Clapton would note that so much of his music is owed to bluesman who historically hadn’t gotten the press and attention that white stars would get for appropriating it. What’s your take on that?

GL: Yeah, you know, for me like, I was really into funk music. Then I got into blues because I discovered John Hammond, and then that set me on a path to discover the blues and learn from all the records — whether it was Muddy Waters or Lightning Hopkins or Robert Johnson or Bukka White or Howlin’ Wolf — I mean the list goes on forever, right? And then I was trying to emulate and imitate their style of playing, and their vocal sounds, like the way their voice sounds. So you know, I was like the white kid from Philly tryin’ to sound like an 80-year-old black guy from the South, and so I definitely developed a lotta vocal inflections when I was singing. So if you listen to my early records, I can’t even really know how I sang like that, really, ‘cause it was such a character voice, in a lotta ways.

But then the hip hop thing: I grew up like a city kid, so we went from basketball to breakdancing to skateboarding, writing graffiti, and then music. And that was kinda the path of this whole inner-city youth. Like there was even that writers’ group ICY (Inner City Youth), which Espo was in. It was a really a cool time to be a teenager in Philly, it was pretty vibrant. There were a lotta house parties, and there’d always be like a jam room at that house party, and that’s always where I would be. And there was a lotta Deadheads too, and South Street was really poppin’ off with punk music and also hip hop. So hip hop was definitely a part of my childhood, and I was really into rap music, like listening to Lady B’s “Street Beat,” Power 99 FM. That radio show was just such a huge part of our life. Friday night we’d have a cassette ready to record the show. Like I remember hearing Public Enemy, Terminator X, and being like, that sound was so intense and scary in a way, you know?

I remember when we started writing graffiti, Friday night would come, this old guy on like 17th and Pine, and he had a little art store in his apartment or whatever, his name was Mr. Zinni, this old Italian guy. Me and my manager — my best friend’s my manager now — he and I would go there like after school, ‘cause you couldn’t buy paint anywhere, right, so we’d go in there like, ‘oh, Mr. Zinni, we wanna buy some paint,’ he was like ‘oh you boys aren’t gonna use this for graffiti now, right?’ ‘Oh, no, Mr. Zinni!’ [laughs] We’d go palmin’ it home — you’d have the paint stashed so your parent couldn’t find it — and then sit up listening to the Beastie Boys’ License To Ill all nervous, and then go meet your homies and run around. That was pretty cool.

So, musically, they all combined. One day when I was playin’ out on the street I started rappin’ some Eric B. and Rakim over this blues riff I was playin’, and then I realized I found something. So like early I’d be playin’ on South Street, it was really vibrant, the homegirls would come by and be like ‘go white boy! Go white boy!’’ And then I moved to Boston, which is really white-bread city. So when I moved from Philly I really kinda felt empowered, because I realized that I came from a place where — even though my parents were well-to-do, I live in a great neighborhood in Philadelphia — you know, Philly is like, you’re on 2nd and Pine, and if you walk to, 3rd and Catherine, that’s like the projects. So in my basketball league, which is Old Pine, by South Street, like I was one of three white kids in the whole league. So I grew up, you know how it is when you’re a kid, you walk around Philly and there’d be like roving groups of kids. And so you know you’d walk down South Street, you’d just always be on your toes. Or then you’d like see a group of homeboys walkin’ on the street and then they’d be like ‘yo, what’s up Garrett!,’ ‘cause you knew ‘em from basketball league. So it wasn’t ‘til later that I felt like, when we put a record out — especially tourin’ in Europe and Japan and stuff like that — the racial issue was always like a big thing for interviewers, and they would say, you know, ‘what gives you the right to sing this kinda music?’

So, I don’t really think about it. And honestly, from all the rappers — whether it was like Q-Tip, or KRS-One — you know, we’d tour with a lotta those guys, and those guys would always be really supportive. We did a tour with A Tribe Called Quest… when we first came out, we did a lot of shows with a lotta hip hop people, and the hip hop crowd didn’t really care to see like, three white boys playin’ instruments. It just wasn’t what hip hop was. So we had some pretty rough shows, where we were just getting hated on. But I remember one time, one rough one was opening up for Guru’s Jazzmatazz project in Boston, we opened that show and it was a mostly black crowd, and it was like, they didn’t wanna see us there. And then my rapping partner was Jasper, this black dude, and when he came up it was alright, but like before or after [laughs]… But most of the artists were supportive. You know, our fan base has mostly been predominantly white people, and you know, the press was the only thing that kinda questioned it. But after being in it, after the first five or ten years on the road, you kinda prove yourself and find your niche, then people don’t really talk about it.

G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

TK: Given the recent loss of Phife Dawg, what do you remember of touring with Tribe?

GL: Well actually, I thought about it years and years ago, but I always kinda regretted on that tour, like Q-Tip kinda took me under his wing a little bit, and he was just real cool, and I was just a kid, I was pretty shy, and I was such a super huge fan of those guys. Q-Tip’s kinda real outgoing and Phife was a little more — I don’t know if he was shy or more just like, kinda keeps to himself, but — I don’t think I really got a chance to get to know him on that tour, so I kinda regret it. ‘Cause if it was now, like I would be more outgoing. But then I was kinda like, really in awe.

TK: You may have touched on this briefly, but where was your first show, and what do you remember about how it felt to be on stage here, in front of friends and peers?

GL: Well like the talent show, that was just a high school thing. Yeah I think it must have been one of those Dobbs’ shows. I’d be really embarrassed, ‘cause my parents were really supportive, and a lotta my music was about rebelling against my parents, so I would be like, kinda uncomfortable when my parents would come to the shows. That’s just ‘cause I was an idiotic teenager, you know? Like now I’m like happy that they’re my best friends. But I remember being at the shows and not wanting to talk to my parents [laughs], just bein’ an asshole! But I’d just remember there bein’ a lot of excitement, and all the shows would be at these little places but they’d just be all jam-packed, and it was just a real attitude where you had to really get out and prove yourself.

TK: Did you feel any pressure at all, as a Philly artist playing home venues for the first time?

GL: I mean I think there’s pressure, but that’s a good thing. It’s not so much pressure, it’s just like the desire to prove yourself, because you had to fuckin’ like earn your shit, and you had to be great, and everybody knew where it was comin’ from, so it’s gotta be real. And I think people recognized, whether they liked it or not, ‘well at least he’s doin’ his thing, he’s got like his own thing.’ Like, if you’re listening to Tribe Called Quest, and De La Soul, and Public Enemy, and Cypress Hill, what we were doing was a different whole thing than that. It had roots in hip hop culture, but it immediately was clear that we weren’t a part of the hip hop culture. Like we were taking elements of hip hop culture, but it’s rock and roll. So the people that were drawn to us were not hip-hoppers, they were just live music fans. And even people that liked rock ‘n roll and blues but hated hip hop would say, ‘oh well I hate hip hop, but I like you guys.’ But we did influence like a lotta rappers, and people that later, after us, put hip hop into their music. And now you know, it’s everywhere.

TK: What Philly venue is your favorite to play at?

GL: Well I’m lookin’ forward to playin’ here [at The Fillmore] tonight!

TK: Who would you say is your favorite Philly artist, or which influenced you most?

GL: I’d probably say George Thorogood. I don’t know if he’s technically Philly, but Delaware Destroyers. He’s pretty influential. Otherwise, my first concert was the Hooters, at the Tower Theater, so I was like a big fan of them when I was in junior high and stuff. But I don’t recall like a ton of music in Philadelphia, although my guitar teacher was a big influence, Waco Smith, he was like a real South Street legend in the ‘80s. He was very influential, ‘cause he taught me for a couple of years right when I was first startin’ to like, come into my thing, you know?

G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

TK: What do you love most about the arts scene in Philly?

GL: I think — I mean I don’t really know it now, ‘cause I haven’t lived here for ten years — but I will say that Philadelphia is a special place, because it’s integrated. I do think the time that we first came out, and it was like The Goats, The Roots, and then us, you know, there’s somethin’ be said. The Goats came first, and they were like an interracial, three-man rap crew with a live band. And that wasn’t really bein’ done, right? And then The Roots came along, and they were trying to recreate live what they were hearin’ on all the hip hop records they grew up listening to, and that wasn’t bein’ done. And then I came along, blended Delta blues with garage rock, and hip hop, and that hadn’t been done. And it all happened in like a one-year span in Philadelphia, so it was like the convergence of our generation — which were like all these skaters, and writers, and city kids that all grew up together — leading up from the late ‘80s to ‘92 and ‘93. That’s when The Goats kinda hit their stride, and then The Roots and I were like ‘93. All the great hip hop of the ‘80s led up to that moment when the next generation of kids that played instruments said, ‘oh, well we wanna recreate rap.’

TK: What did you find most frustrating, if anything, about trying to create or perform, or grow as an artist in Philly?

GL: That’s like a tricky question, but I mean honestly, I think Philly has a way of kinda hating, even though there’s a lotta love. I just always felt like there’s a lotta haters in Philadelphia. Like I felt like — for instance, we’re a pretty big band to come outta Philadelphia, and we never got the cover of City Paper, ever, you know? Except for one time…The Roots were doin’ a photo shoot at Silk City diner, and they had the idea to recreate my first record cover, and then they looked over, and I was sittin’, havin’ lunch with a friend. And the photographer was like ‘yo, get G in!’ So I was in their cover. But yeah, I always felt that there was a lotta haters. But I think the best thing about it was the integration of different cultures, and just the way that kinda reflects Philadelphia as a city, and also because Philadelphia is kind of an underdog town. The people have an underdog mentality like Rocky Balboa, and I think that that spirit — I mean it sounds kinda corny — but it really is like the spirit of the people of Philadelphia. And I think that goes for the musicians. Like there’s something in the water that’s like, it’s dirty, it’s like the music that comes outta here is just real, for the most part. I mean there’s plenty of cheesy shit, but I think for the most part there’s a certain realness that comes from the musicians that are comin’ outta here. Because yeah, it’s overshadowed by New York and DC, you know Boston’s like super clean and white-bread, not too much grit. And Philly’s just got that gritty, you know, thing. But because of that, the frustration is that, because it’s a harder [sort of] people here, they’re harder on the musicians that come to play here, and even that come outta here. There’s not like a [feeling of] ‘oh, yeah, let’s really support these guys!’ That’s more on the industry, I mean. The people support, but the Philadelphia music industry doesn’t support Philadelphia artists.

G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

TK: What Philly neighborhoods have you lived in, and which made you wanna stick around or bail?

GL: Well my first neighborhood was Center City, like 12th and Waverly Walk. And then I lived at 2nd and Pine, so Society Hill. And then I moved to Boston, and I came back, and I lived in Fishtown, on East Allen Street. Then when I had a kid we finally bought a house in Queen Village on 3rd and Catherine. And then I moved to Northern Liberties on Hancock Street. So I dunno, I love all the neighborhoods. I think Queen Village, I definitely regretted selling that house, but that was like an emotional thing. That’s a great neighborhood. And of course Fishtown — it’s funny, [my manager and friend] Chris used to live behind Silk City, and I lived over on East Allen Street, so we used to walk these streets a lot and it was always so dead around here at night, it was pretty cool.

TK: How have you seen the city change in your time here?

GL: I mean think mostly just the development, of like, north from Society Hill, first Old City. ‘Cause when I was a kid, there was nothing, and then that became like the cool place, and more people started living there, and it became as great as it is now, and then that pushed Northern Liberties and Fishtown. So, I think it’s been exciting to see especially a lot of the cool architecture they put in Northern Liberties and stuff. But it’s cool to see the city develop. I do feel like the city’s really fucked up their city planning. Like if you go to New York or Boston, they’ve nailed it, and it’s like Philly just can’t seem to wrap their head around the fact that they got all these rivers that people wanna walk along, but they can’t. So it’s like, fail. It’s like a terrible fail. There should be a jogging trail that goes from the fuckin’ stadiums to fuckin’ Poconos, you know?

TK: What’s your favorite Philly beer — e.g., PBC, Yards?

GL: Oh, Yards.

TK: 1980 or 2008 Phils?

GL: 1980 because I went to that shit! I was eight. I remember they won, and I thought they won the whole thing. And my dad was like ‘no, they have to win more..’ And you had Tug McGraw, Mike Schmidt, Pete Rose. Yeah I definitely grew up going to [see] the ultimate Philly teams, like the Sixers and the Phillies, and the Flyers.

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN

- G. Love | photo by Josh Pelta-Heller for WXPN