Maximizing Time: Philly’s Justin Duerr on constant immersion in music, writing and visual art

Justin Duerr performs with Northern Liberties | photo by Yoni Kroll

You might know Justin Duerr from Resurrect Dead, the award-winning documentary he helped make about Toynbee Tiles, the colorful and mysterious messages embedded in roads in Philadelphia, NYC, and elsewhere. You might know him from his bands, including the long-running ‘ghost punk’ outfit Northern Liberties or the acoustic duo Get the Great Cackler he does with his partner Mandy Katz. You might have seen his one-of-a-kind art on a t-shirt or a show flyer or maybe hanging on your friend’s wall. Or you might just have seen Justin intently walking around Philadelphia, tattoos stretching from the side of his head to the tops of his hands – including a portrait of pop singer Cyndi Lauper gracing his left hand – and wondered, “What’s up with that guy?”

Opening Friday at the Magic Gardens on South Street, Time’s Funeral: Drawings and Poems by Justin Duerr is a gallery exhibition including small, stand-alone pieces and huge posters that are part of an on-going storytelling series that Justin has been working on for almost two decades. As an added bonus, he’ll be playing music at the opening night.

Justin also recently completed his first book, a history of the obscure turn-of-the-century artist Herbert Crowley, mostly known for his Wigglemuch cartoon that ran in the New York Herald in 1910. Crowley was an accomplished artist who was part of the avant garde art scene in New York City. But after he left the city in the 1920s for London and later Zurich, he was all but forgotten. Justin’s project, The Temple of Silence: Forgotten Worlds and Work of Herbert Crowley aims to change that. The book got close to $100,000 in initial backing online and will be published by Philadelphia publishing house Beehive Books later this year.

Justin Duerr paints the poster for Time’s Funeral | photo via nycstreetart

ART EXHIBITION

The Key: Why is it called Time’s Funeral?

Justin Duerr: It sounds like it means something, so that’s a good hook. [laughs] I did put some thought into it. Mainly it’s an evocative title. You hear it and you think, ‘Well that sounds like it must mean something. Maybe I should go to the show and see what it means, see what it’s all about.’

If I saw something called Time’s Funeral I’d probably want to go to it. Time, that’s pretty important, I’d want to go to its funeral ceremony. I mean, you’d hate to miss that!

TK: It’d be hard to miss!

JD: That makes it important. That gives it a sense of importance, of gravitas.

A lot of time goes into the artwork. Pretty much all the work in the show, it’s real meticulous so it’s all real time consuming. I’ve read a lot of stuff about time and what time is. I’ve got Einstein’s book on relativity for dummies and it’s still over my head. People have this idea – and it’s accepted by physicists and stuff – that time is the 4th dimension and it came out of the Big Bang as an aspect of space or whatever.

It’s a mind-melding sort of thing because it’s finite. There’s only so much of it. It’s like space: there’s only so much space and there’s only so much time. Literally. It ends, it runs out. It doesn’t actually move; we perceive it that way but that’s not actually objectively what’s happening. It doesn’t have motion. So I guess with all the time I spent working on the drawings I felt like Time’s Funeral was a pretty good title.

TK: Do you ever feel like you’re running out of time?

JD: Everything’s running out of time.

TK: I think of you as someone who is bad at sleeping and decent at maximizing the amount of time you spend doing everything you need to do.

JD: I have a larger thought about that but I’ll let you get to that question. That has to be an answer to a question.

TK: Wait, what’s the question?

JD: I can’t remember exactly what the question was, but my answer is that a nice thing about the art stuff is that you’re involved in something bigger than yourself that can outlive you so a hundred or two hundred years or a thousand years after you’re gone, you still could have contributed something to the human conversation.

TK: Does that make art infinite in time? Or at least in contrast to the human body.

JD: Definitely not infinite but it could last 150 years instead of 70. Also you’re part of a conversation that started a long time before you. Especially if you do art that has some craft element to it. I’ve looked at a lot of stuff from thousands of years ago to get craft ideas and stuff from. Things about color theory and composition and stuff like that. I’m drawing influence from stuff that’s 3,000 years old and 5,000 years old. I look at art from 30,000 years ago and 40,000 years ago, that art that people have leftover in caves and shit like that, and I take [the concept of] the horse with the person on it. [points to drawing on postcard] People have been doing that stuff for 30 or 40 thousand years. What they were using it for is I’m sure totally different.

It’s neat to just feel like you’re part of a lineage that’s going that far back and maybe will continue that far forward. But even if forward it only continues for 50 years after you’re dead, it’s just bigger than you as an individual.

TK: This exhibition will have the Decades of Confusion poster series?

JD: There’s ones that connect to each other but a ton of the art in this show is individual drawings, standalone drawings. I forget how many pieces are in the show but it has to be approaching a hundred or over a hundred. It’s a ton of work and the biggest ones are those long scroll-like posters and they all connect to each other.

TK: They’re going to be displayed in a way so you can start at one end of the room and go from there?

JD: Some of them. The way that room is, there’s not enough space to continuously connect a ton of them but I think there’s two or three that connect and some of them will be one on top of the other. I told them to just cram things in; I don’t want to have any empty space. It’s not minimalist, it’s maximalist.

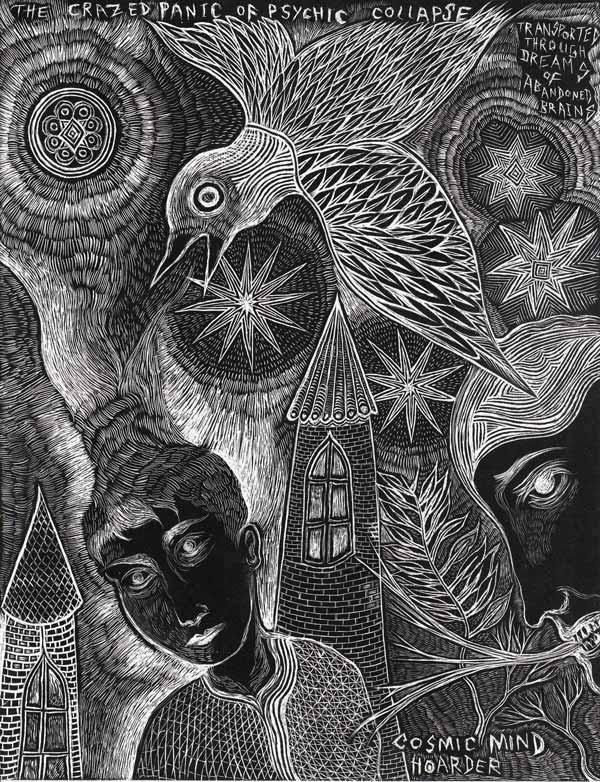

Crazed Panic of Psychic Collapse by Justin Duerr | courtesy of the artist

POSTERS

TK: I have one of the posters in my house and I don’t look at it and think, “I’m only getting part of the story” even if it’s part of something larger. I mean, you get to see everything, but it’s rare for other people to see more than two or three of them.

JD: I mean, first of all I have them all on my website. You can look at them but I don’t think many people do that. I made the first one in either 99 or 2000 and my master plan is to keep on doing them and connecting them to each other for my whole lifetime if or until I get a diagnosis of a fatal disease or some kind of progressing thing that’s terminal and then I’m going to use my time in the hospice or whatever to make one that connects the last one to the first one. But the longer I live the cooler it will be because the longer it will be.

My thinking with that was that if I live long enough and I make the thing long enough it will become undeniable. You have to do something undeniable or people will deny it. There are some people who are born into a higher place and they get to kind of half-ass things and they still get all sorts of accolades for it. But that wasn’t my circumstances. So in order to get any kind of props for something I have to do something that is undeniable. It has to be, like, literally the largest drawing anyone ever did. And if I do that, on a scale of 1-10 people will give it like a five.

TK: Maybe you should work on a 10,000 page mythology where you use cutouts from magazines to create a weird Catholic fantasy mashup [like Henry Darger did throughout his lifetime in creating In the Realms of the Unreal.]

JD: That was the thing with him! It was undeniable. And he was lucky enough to have a landlord who could get that it was undeniable because let’s face it, nine times out of ten with people like him that stuff just gets thrown away.

I think that is actually technically the longest single piece of fiction written by an individual person. Even though it’s kind of unreadable, it’s just undeniable.

TK: When you made the first poster did you go into it thinking it was going to be a series?

JD: No! Seph gave me the idea. I made the first six of them and then when I was living with Seph [at the Church of Divine Energy, a Southwest Philly warehouse venue active in the early 2000s] somebody came over and I was showing them the big drawings and Seph was, like, “The cool thing about them is that he makes them so they all connect to each other so he’s just going to work on them his whole life and they’ll all connect and it’s just crazy!”

I thought, “That’s not true, but it’s a better idea than what I had been doing.” So I decided to make it true. I backtracked and did in-between ones to make the ones I had already done connect and then from number six onward they all connect.

TK: Can you do a synopsis of the ongoing story?

JD: No. It’s too vast. There’s repeated characters and there’s repeated themes but I mean when you have something that’s a lifelong project like that and you’ve been working on it for 17 years… and actually even before that.

Cause the backstory is that at that abandoned hotel where that restaurant is now next to the A-Space where we used to live, me and Kevin [Riley, Northern Liberties bassist] and Gary and some other people. My brother. That room we lived in there, there was one winter that was that big ice storm and I was living off of dumpstered hotdogs from the APlus and we got food poisoning and it was the worst winter of my life, this apocalyptic scenario. I think we were heating the place with propane? Something like that? And we were running out of oxygen. So it was this funny thing where you had to crack the window in order to get in oxygen but the whole point of the propane heater is to create heat. So you’d crack the window and now you’ve got cold coming in. So you close the window and you start to run out of air.

It was this horrible situation. I did this drawing on the wall and when they demolished that building finally that drawing was still on the plaster of the wall of the room we were in. I think we were on the third floor or the fourth floor and it was cool because it was a big old billboard-sized piece of plaster stuck to the building with this marker drawing on it. The cool thing about that is that I’ve seen people do that with graffiti before, with spray cans and stuff, but it’s usually something quicker. It’s something where somebody would go in and they wouldn’t spend more than a couple hours at the most but this thing you could tell right away from looking at it that somebody spent a couple months drawing it.

It was pretty impressive for people to see it up there like three stories up in the air stuck to the side of this building. It’s this drawing with all these little monsters in it and stuff and I used to always see people taking pictures of it, people would stop and take pictures of it. I don’t have any pictures of it but it did give me the idea that if you spend that much time on a drawing, whether or not it’s even good, people will just appreciate the time you put into it. That planted the seed in my mind to where then I was living in the Catbox [a house in West Philadelphia where this journalist saw his first ever basement show: Myles of Destruction, Captain Crash, Sputnik, and Eulogy, Justin’s band at the time] in 99 or 2000… it’s funny because when I started doing those big drawings I tacked them up to the wall and it was giving me these terrible hand cramps and somebody was, like, “Why don’t you try drawing it on the floor?”

TK: Is that what you do now?

JD: Everything is done on the floor. Even my small drawings. I can’t draw on the table. I have to be sitting on the floor [or] I can’t work.

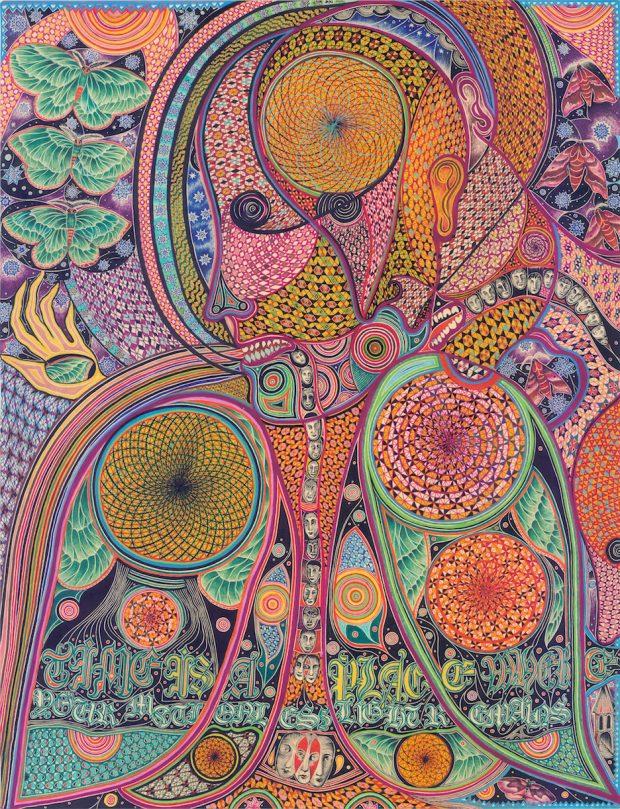

Time Is A Place Where Your Motionless Light Remains by Justin Duerr | courtesy of the artist

ZINE

TK: When did you start doing your zine?

JD: August 95 was the first issue. I went to the Wildwood Boardwalk and sold 200 copies in one night. That’s why I did the zine! [laughs] Butch [notorious West Philadelphia denizen and the eventual singer of Eulogy] was always trying to get me to go to the Wildwood Boardwalk and I didn’t want to go. He had this friend at a Kinko’s and as an inducement to go to the Wildwood Boardwalk and party with him, [Butch] was like, “Dude, you do art stuff. Why don’t you go to Kinko’s where my friend works and just make a zine? Run off as many copies as you can for free and when we go to Wildwood Boardwalk just sell it drunk people, you’ll make so much money.”

He always had these scammy ideas that would always come to nothing. It was his one thing like that that was true. It really worked. It wasn’t even much art. It was pretty much all cut-up poetry – where you’d cut things out of books and rearrange them – and then just weird little poems and stuff because somebody had a word processor, which felt really advanced at the time. So I processed all these words and I ran off 200 of them and we went to the Wildwood Boardwalk and I walked up and down the boardwalk and I just approached hoards of drunk people and said, “Want to buy my zine? It’s a dollar!” And people were, like, “What’s a zine? Wait, you drew that? It’s a dollar? I’ll take one.” I sold 200 of them in one night. I got a pen pal from that that I wrote to for three years. There was one lone goth, a boardwalk goth, who got one that was actually, like, “I’m feeling this.” Everybody else was I’m sure the next morning, “Oh my fucking God what is this thing?!”

TK: How many issues are you up to at this point?

JD: The next one is 67. I’m doing the Philadelphia Zine Fest this year and I’m going to do issue 67. The Zine Fest is now like getting tickets for the Pope. It’s ridiculous but I did it. I actually did it.

TK: How did Time’s Funeral end up at Magic Gardens?

JD: They just asked me to do it. Like everything in my life that’s ever worked out – what’s that Young Marble Giants song that Hole did a cover of, “Credit in a Straight World”? – it can only happen by accident. If you try, it’s doomed to failure. I had some stuff in there before through Coalition Ingenu, so I guess I was on their radar because of that.

TK: I like Magic Gardens because it’s this typical Philadelphia unforced weird. Do you know the phrase in Latin ‘a priori’? It refers to something that is accepted as always being a certain way. And I feel like Magic Gardens is a priori weird.

JD: Isaiah Zagar [the artist behind the space] came to one of the Toynbee movie showings and he was, like, “I have an idea for a documentary: they should do one about you!” I was, like, “Sweet.”

Justin Duerr performs with Northern Liberties | photo by Yoni Kroll

MUSIC

TK: A friend of mine who is a pretty well-known musician and writer has complained a lot about being asked to compare the two, as he sees them as one in the same. Sometimes he writes songs and other times he writes stories. Is that similar for you as someone who is a musician, artist, and writer?

JD: I feel like [being creative] is a disease or something. It’s like a curse, in a way. You don’t have a choice but to do it, to participate in this thing that’s larger than you. Everybody knows this about creative-type people. They’ll do stuff that makes no sense, like you would go without eating in order to do this. You would definitely sacrifice your life. Of course. Why? I don’t know. Maybe you just have to do it, it’s just born in you.

It sounds corny sometimes when artists are, like, “I have to do this.” But I really think there’s truth to it more than some kind of statement of pride. It’s not some ego thing where you’re just kind of, like, “You don’t get it, man, I have to do my art.” But you do kind of have to do it. …You can’t help it.

I kind of inherited that creative personality and I just kind of have to be that way. And then it comes out in all different ways. I learned a couple guitar chords when I was a kid. I learned how to play the drums. I always read a lot so I got a knack for being able to mimic that and write a little bit. And so I just do whatever fits the medium. Things I want to express but can’t draw, maybe I can write them. And if I can’t write them or draw them, maybe I can make up a song about them. It’s just whatever fits the medium.

TK: Does it all come out of the same well of inspiration and is just expressed in different ways?

JD: It’s not inspiration, it’s just the way I am. It’s a personality trait. But yeah, that personality trait comes through all different avenues depending on what it is I want to express.

TK: Is this something you think about or does it just kind of happen?

JD: It’s something that happens but the medium, the materials I’m using – whether it’s song or visual art materials – I’ll get in different moods about what I feel like doing.

TK: Speaking about songs, let’s talk about the music you’re making. Northern Liberties is coming up on 18 years?

JD: We played our first show in February of 2000.

TK: There are new recordings soon and you’re going on tour next month. That’s the first tour in a while, right?

JD: We’ve done little weekend things but we haven’t done anything more than three days in a row. The whole thing is based around playing [the Realms of the Fourth Eye

festival in Dallas] Texas. My brother is flying home after the Dallas thing so it’s pretty strange because it’s a six day tour from Philly to Texas and then Texas is the end of the tour and then me and Kevin will drive home.

TK: What else is going on musically? New Invasive Species recordings?

JD: If we get a bass player. Geb the Great Cackler is always playing. We have two new songs. We should have more new songs but we’re the least popular of the three bands so we don’t feel very motivated. Actually, none of the bands are popular but out of the three we’re the least popular. [laughs]

TK: What do you get out of playing in Geb the great Cackler versus Northern Liberties?

JD: I mean, it’s just pretty different. It’s acoustic, for one thing. It’s weird cause that acoustic stuff, I’m not a real stage fright person but that’s the closest I get to it. You can’t hide anything. Northern Liberties it almost doesn’t matter what you do: it’s loud and there’s delay on the vocals. You can’t go wrong.

With acoustic stuff, if you play the wrong notes you better mean it. There’s no hiding it. You need to own it. Which we do, because believe me we play a lot of wrong notes but we try to just own it. People have a harder time with that with acoustic music because there’s been so many decades of loud, aggressive, agitated music where it’s okay for it to be off-kilter. But with acoustic stuff, people are, like, “You’ve got to have chops.” And we don’t have chops.

Geb the Great Cackler is the one band that I play in that’s really punk. None of the other ones are punk. We’re the punk band.

TK: What makes you the punk band?

JD: We’re really grating. It’s actually off-putting to people. We’re a real room-cleaner. Invasive Species is very unphotogenic; we’ve played [just] one show where somebody took a picture of us and that’s was because I asked them to. But as far as our sound, I don’t think people necessarily like it but [they] stand there and tolerate it.

TK: You’ve been playing in bands for, what, 25 years now?

JD: Actually, since 91. I’m 41. My first band was in 91 and my brother played drums and I played bass and sang and our friend Mike Zigler played guitar. He was a shredding metal guitarist.

We didn’t play a show or anything like that but we did record a bunch of songs.

TK: This was in Biglerville?

JD: Zig lived in Bendersville but same difference. Culturally pretty similar, you know how it is.

TK: Was playing music sort of an escape when you were growing up?

JD: Oh my god, how fun to find anybody even to play music with.

TK: I remember hearing stories from Kevin about your hometown and how everyone grows up and works at the apple processing plant and gets married and has kids and they do the same.

JD: It’s like that song “Kerosene” [by Big Black]. That’s that town, that’s what they made the song about. It’s to a T.

TK: I know that a bunch of the people in your friend group back home dropped out of high school and moved to Philly. Was playing music part of the fuel for that?

JD: Yeah. We would have done it anyway, though, it was just one of those things where it was, ‘anything but this.’ We weren’t college material so what else are you going to do, right? Sometimes I wonder what it would have been like had we just stayed there and been, like, “We’re weird, we’re here!”

It was funny cause my dad, he worked at that apple factory basically his whole life. And my brother started working there … and I remember my brother telling me this story where he was, like, “Yeah, I was telling our dad, ‘The factory foreman is such an asshole. This guy is just an ass-hole. Day in and day out he’s just singling me out cause I’m the new guy on the line.'”

And my dad’s comeback or whatever, his message of hope, was, “You’re going to be working at that apple factory long after that guy is gone. That guy is going to come and go and you are still going to be there.”

TK: You worked on the fishing boats back in the day. You do painting jobs and stuff now, right? What sort of other weird jobs have you had? I mean, not weird, but just not standard.

JD: I’ve had some weird jobs. It’s not an exaggeration. [laughs]

I work for a landlord. I’ve been working for him on and off since I stopped working on the fishing boats, so for about 17 years. … I’ve actually gone down to part time because I’m trying to do art stuff a bit more, even if it’s not paying the bills as much.

It’s weird because in all the time and all the stuff with the Toynbee movie, I never expected [to make money] except in roundabout ways, like maybe it gave my art a little higher profile so I sold some art or something like that. But I mean, I think I got like a thousand bucks all told from that. But the book, I got some money from it. That makes me think that maybe I should work my job less cause isn’t that what you’re supposed to do?

I think people do weird things [in these situations] like get a manager. Bands all have managers now and it’s, like, “Bands have managers?” There’s no DIY anymore. It’s weird cause having a manager or having an agent, it’s like what I’m saying about these art shows: you can’t get one. They have to come to you. And the only way they come to you is if you don’t need them anyway. It’s weird catch-22.

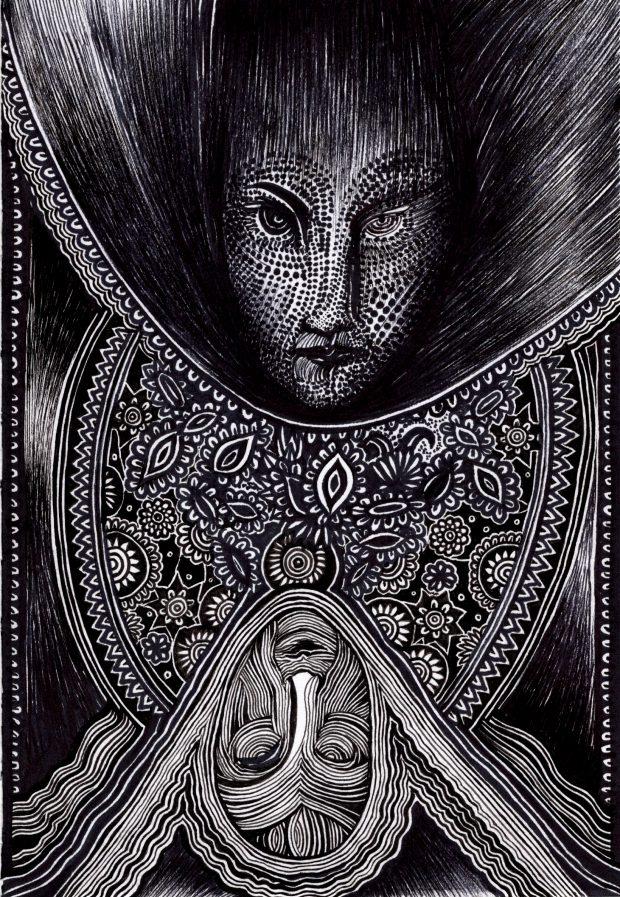

Another Becomes the Other by Justin Duerr | courtesy of the artist

BOOK

TK: How did the book come about?

JD: I pitched the Herbert Crowley as an article to a couple blogs and none of them wrote back.

TK: So you just decided to write a book on your own?

JD: I literally thought, “I figure I’ll just put this in my zine.” The coincidental thing that happened with that was – speaking of that Toynbee movie and how it gave a higher profile to this that or the other thing – the publisher [of the book] Josh O’Neill, he had never seen the Toynbee movie until 2015. He watched the movie … and there’s a little thing at the end that I had Jon [Foy, director of the documentary] put where it’s, like, ‘Justin is researching Herbert Crowley.’ And then Josh O’Neill was, like, “Oh my gosh, I love Herbert Crowley!” He knew his work. Nobody knew about it except through that Art Out of Time book.

It was super coincidental and super lucky happenstance that somebody who was interested in that and was a publisher and was local happened to see it. Somehow he got my number and he called me at work one day and I talked to him on the phone at work for two and a half hours and he was, like, “I’m doing a book of this. Send me the stuff.”

TK: Was it important to you to have a publisher that’s based in Philly?

JD: Not really, but it’s super lucky. It’s just more convenient because I can go meet with him.

TK: That’s also the nature of Philadelphia where even though the various music and art scenes aren’t small, everybody knows everybody. Speaking of which, do people still recognize you from the Toynbee Tile doc?

JD: It happens I would say once a week. And it happens in weird circumstances like I’ll be showing an apartment and somebody will be, like, “I know you from somewhere.” One day this lady was, like, “I know you from somewhere but I can’t place where” and I said, “I don’t know, maybe you know someone I know or something?” And then her husband or boyfriend or whomever was, like, “I know where.” And she says, “Where?” And he goes, “I’ll tell you later, it’s weird.”

And I was, like, “This is weird. It’s gotten weird.”

TK: What did you get out of the experience of making the Toynbee documentary? What the book have come about without the movie happening?

JD: Well, first of all the book wouldn’t have happened without the movie because the publisher saw that I was interested in the subject of the book from the movie, literally. There’s a lot of nebulous hard-to-put-your-finger-on-it stuff from that. People have that weird obsession with celebrity. And I’m nowhere near the realm of Cher [for example]. I just saw Cher on TV, by the way. Her outfits are amazing. They had her costume designer on the show I was watching in the dentist’s office. The costumes are all based on [historical designs from] when they killed off all the birds, back in the 20s or whatever, because women wanted feathers for their hats and stuff. But I’m, like, “I understand why they killed off all the birds. These hats are amazing.”

But you know, it’s not on that level. It’s like once a week. What’s weird is that it’s not relegated to Philly. I’ll go to Maine and somebody in a diner will be, like, “I think I saw you in a movie!” People have that obsession. I don’t think people have bad intentions; it’s just kind of the way that we’re wired as a species. Humans have that instinct of being, like, “I saw a movie this person was in so they’re my friend.” And they’re not your friend. You don’t actually know them.

They could be an asshole. There’s that saying “Don’t meet your heroes.” Maybe they are nice but if they are it’s coincidental. Terrible people can make good art. It happens all the time. It’s one of the things that uncomfortably reminds us that we’re all human.

[The movie] was a life lesson in that unexpected things can happen that are really positive. That was a real shock that it did so well. That was really out of the blue. It was an esteem builder. I was always a low self esteem sort of person. I still am kind of by nature but it was a bit like, “Whoa, that’s crazy, that could really happen!” Unexpected bad stuff happens all the time so I guess every once in a while unexpected good things can happen.

TK: Why do you think people want to talk to you about it?

JD: Maybe they want a question answered about it. Sometimes it’s legitimate, sometimes it is an actual question they couldn’t find an answer to otherwise and I’m happy to tell them. Sometimes I’m just, like, “You can just look it up!” Whatever, I’ll tell them. I’m friendly.

I figured this statistically one time: I looked up how many people watch Netflix, what percentage of them leave reviews, and then I looked up how many reviews it had and I did some half-assed unscientific number crunching and I figured over a million people have seen the film. That’s crazy. So probably a couple million people have seen it.

TK: I was going to question your math but I realize that a couple million people watching a movie that came out in 2011 that was in theaters, on Netflix, can be purchased on DVD, and is just out there on the internet actually makes sense.

JD: Nobody sees anything until it goes on Netflix streaming. [Before it was online] I was, like, “It played in film festivals and stuff, a ton of people have seen it.” I was breathing a sigh of relief. Again, not to be looking a gift horse in the mouth or whatever, but I thought, “Oh good, it’s over.” But then it went on Netflix streaming.

I used to get maybe two emails a week of people asking, “Hey did you ever catch the guy?” When it went on Netflix streaming, no lie on that first day I think I got 50 emails. In one day. It sort of went down from there, it went down and up, but the whole time it was on Netflix streaming I’d get at least five per day. I couldn’t possibly keep up with it.

There was a very small amount of them that were really over the edge. Don’t send me nude photos. It’s creepy. The weird thing with that type of stuff is that those people didn’t stick around.

TK: They didn’t stick around after sending you obscene messages?

JD: No, but somebody sent me a knitted pigeon. They crocheted a pigeon and mailed it to me and then after it went off streaming they were, like, “I’m good.”

TK: Is it weird that your legacy as an artist is partially tied into another person’s work?

JD: I think it’s weird but I think it’s kind of cool. There’s a certain percentage of people that think that Toynbee movie is a self-serving thing. First of all they think I made the movie and that it was self-aggrandizing to put this section in about myself. And I’m, like, “That would be self-aggrandizing and egotistical but I didn’t make the movie and it wasn’t my call to put that section in.” In fact, I felt weird about it, because I was afraid people would think that. But Jon was, like, “It really drives the story along. And some of the stuff is just uncanny. How uncanny that you guys are both into pigeons and both have the name Birdman?”

It is uncanny. He put it in but there’s a certain percentage of haters who are all, “I get it, artist guy just wants people to see his art and he’s just using this other guy’s thing.” And you know what, I guess it’s kind of a fair criticism but it’s not really.

But here’s the thing: I’m going to break some rules with this art stuff because you’re not supposed to be an academic and an artist but I am. I mean, I’m not collegiate, I never went to school. But I’m into researching things. I loved researching for that Herbert Crowley book, it was just a total joy to research the stuff. I mean, I love it. I love going into archives and digging up microfilm and stuff like that.

I see the Toynbee movie as a research project. I didn’t see it as, like, [movie announcer voice] “It’s an urban mystery!” Well, yeah, it was an urban mystery, but it was research. That’s what I liked about it. To have that parlay into this book that was more a classic, like, go to the libraries and archives and stuff… I mean, I also did some real spelunking. We went to that abandoned house in upstate New York and found letters from 100 years ago in the rubble. I love stuff like that.

TK: What have you been obsessing over recently?

JD: Birdsville. I got really into Birdsville. Albert P. Greim and Birdville.

TK: That’s the abandoned bird sanctuary from a hundred years ago, right? Where the creator was basically just dedicated his life to birds and promoting birds and just everything to do with them. Where in New Jersey is that?

JD: Toms River. He also had another Birdsville that nobody knows about. Birdsville One, which was the first one. I just got into doing really deep research about that and I found out a bunch of stuff about him. He had a theater, a vaudeville theater in Toms River before he did Birdsville. They showed Krazy Kat cartoons and stuff.

I found a news article from 1908 where he had jury duty. The New Jersey Courier, they’d always be mentioning him because Toms River is so small. So the local goings on about Toms River would be, “Albert P. Greim of Birdsville…” So they list who had jury duty and it lists their occupation so it’s like: Stanley C Grover of whatever street, tailor. And it says: Albert P. Greim, birdman. That’s his occupation. I love it.

I found some old [articles] that he wrote about how to make your chickens happy where he’s talking about, “When I first started to get into fowl I realized that they need high-arched windows with stained glass in order to make them have peace of mind. There’s nothing more pleasurable in life than heating up rocks and burying them under some dust and watching your chickens take dust baths on them.”

TK: Do you feel like there’s anything that connects all these disparate topics? I mean, except for you.

JD: Birdman. Occupation. That’s what you should call the article: “Justin Duerr, Occupation: Birdman.”

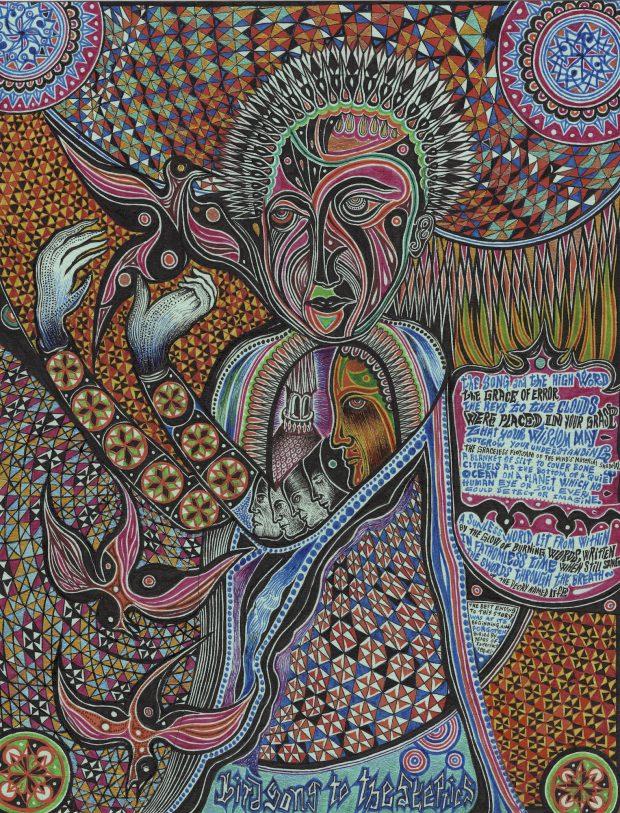

Birdsong to the Skeptics by Justin Duerr | courtesy of the artist

TK: Herbert Crowley wasn’t a birdman.

JD: That’s true. He’s the exception to the rule.

TK: But isn’t the Wigglemunch, Crowley’s best known character, a bird?

JD: No, it’s just a big old buzzard hatching out of an egg on a cliff.

TK: That’s bird-like.

JD: It’s a bird. It’s a straight up bird. He did a couple bird things. But he wasn’t a straight up birdman.

TK: What was your initial introduction to Herbert Crowley?

JD: Northern Liberties was on tour, I think it was 2008, in Blacksburg, Virginia. We used to stay with this friend of ours Whitney Waller who was an artist and real supportive person on the music scene back then. I don’t know if she still does stuff. She’s got this big really interesting collection of art books and I woke up in the morning and overheard Kevin saying to her, “Justin’s going to find something in this book that he’s totally going to be obsessed with.”

And I was kind of grumpy about it. I remember thinking, “Kevin thinks he has my number. People think they know me, they think they’ve got me all figured out. You can’t just figure me out. I’m the J Man. I’m the Birdman. You can’t just dial it in. Nobody has me all figured out.” Then I looked at the book [a copy of Art Out of Time] and I was thinking I was right until I came across the Wigglemuch. Oh my God. Other than Krazy Kat it’s the only comic strip that ever really blew my mind, just in that way where it’s really art. It’s a whole total piece of art. I’m not against comic books as art but it just takes a lot. I’m a real snob about it.

I was really, really, really blown away by this comic strip. It was completely incredible in every way. Giving me goosebumps kind of stuff where I’m just, like, “What dimension did this thing crawl out of?!” I flipped to the back of the book right away because there’s little biographies of all the artists and it reads, “Herbert E. Crowley – Birth date: unknown. Death date: unknown.” There’s little question marks and he says, “Herbert Crowley occupies the biggest information gap in this book. Other than the existence of these strips, nothing at all is known about his life or work.” And I was, like, “Alright.” [laughs]

TK: What was it like doing this sort of academic writing for the first time?

JD: It was weird because I had to look at a lot of other academic writing to learn the language. I had to learn the style kind of on the fly. Basically academic writing isn’t academic enough and you always find flaws, there’s always mistakes. I’m always really irritated by the mistakes because these people are supposed to be academics and I’m, like, “How can they be spelling these things wrong?” Anyway, M. Sue Kendall in [the book] Charles Burchfield: North By Midwest, she has got an essay, “Serendipity at the Sunwise Turn: Mary Mowbray-Clarke and the Early Patronage of Charles Burchfield” That essay is impeccable. Everything about it is perfect. I totally learned the whole style from it. [For] that piece of writing she did everything. Then the other one was Cleota Reed. It’s a book about Henry Mercer and the Mercer Tiles which I got because of researching the Birdsville stuff because he used those Moravian tiles. That book is absolutely mind-boggling [because] everything’s there.

TK: Researching this book took you a bunch of places. There was Switzerland to meet descendants by marriage.

JD: Right, by his second marriage.

TK: And to New York City. To Upstate New York.

JD: To Austin, Texas. And I didn’t go to Canada but I had people in Canada that were looking stuff up for me because he lived in Toronto.

TK: And if somebody asks why, what’s your answer? I mean, except for “Why not.”

JD: Somebody needed to do it. Somebody had to do it. When I saw that thing in the book saying it’s an information gap I thought, “Somebody needs to do this! The work is amazing.” I’ve got to say, I called the Metropolitan Museum of Art trying to get scans from them and the guy looking stuff up said, “Why I have never heard of this artist, this is amazing.” They didn’t even know they had it.

Time’s Funeral: Drawings and Poems by Justin Duerr opens tomorrow at Philadelphia Magic Gardens and runs through November 15th. More info can be found at Facebook.