Bruce Springsteen in Haddonfield, New Jersey | photo by Frank Stefanko

When Springsteen Came to Haddonfield: New Jersey photographer Frank Stefanko reflects on working with The Boss

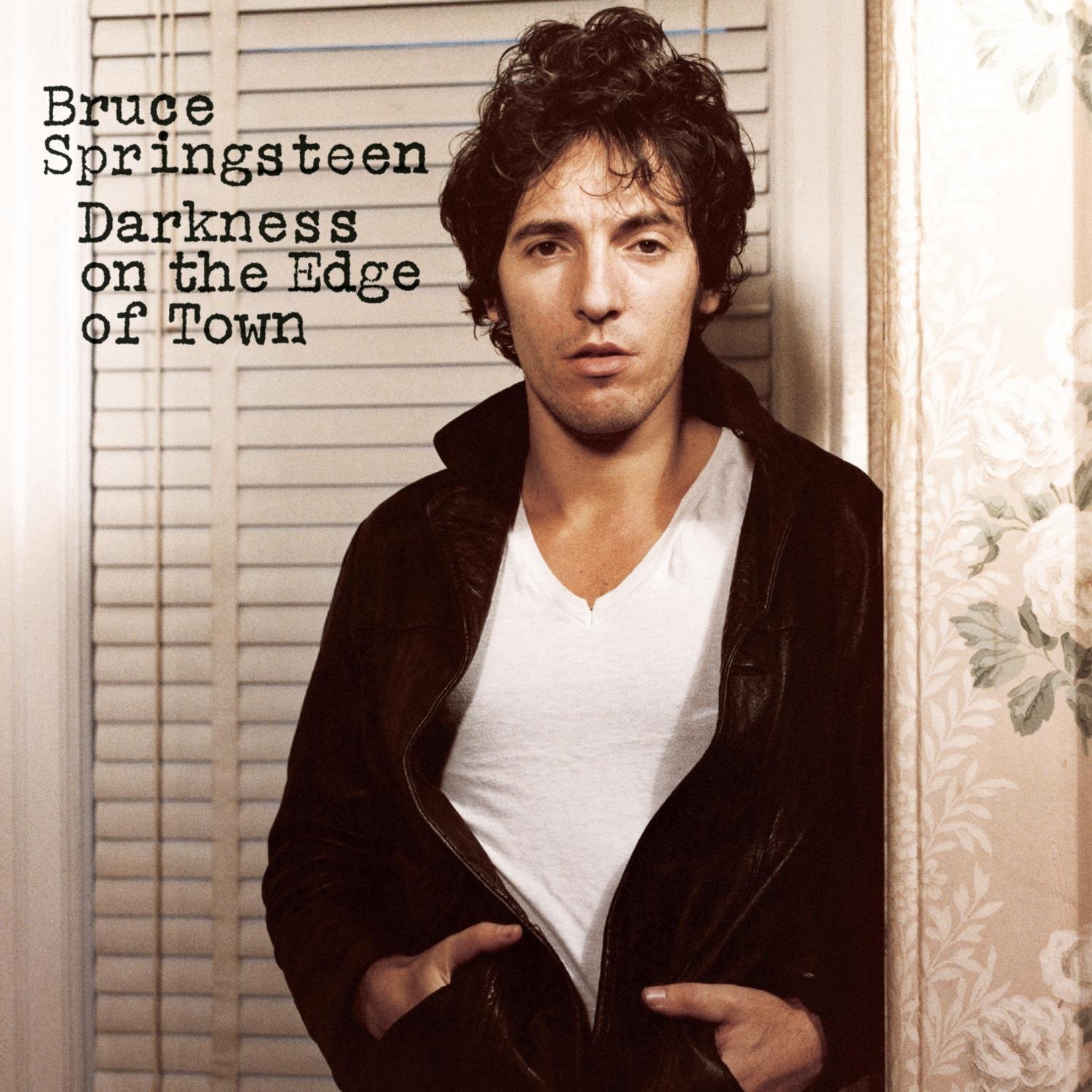

Looking at the cover art, you’d probably guess that the iconic photo of Bruce Springsteen on Darkness on the Edge of Town was shot in his native Asbury Park. Or maybe in nearby Homdel, New Jersey, where he bought a farmhouse to write the album in.

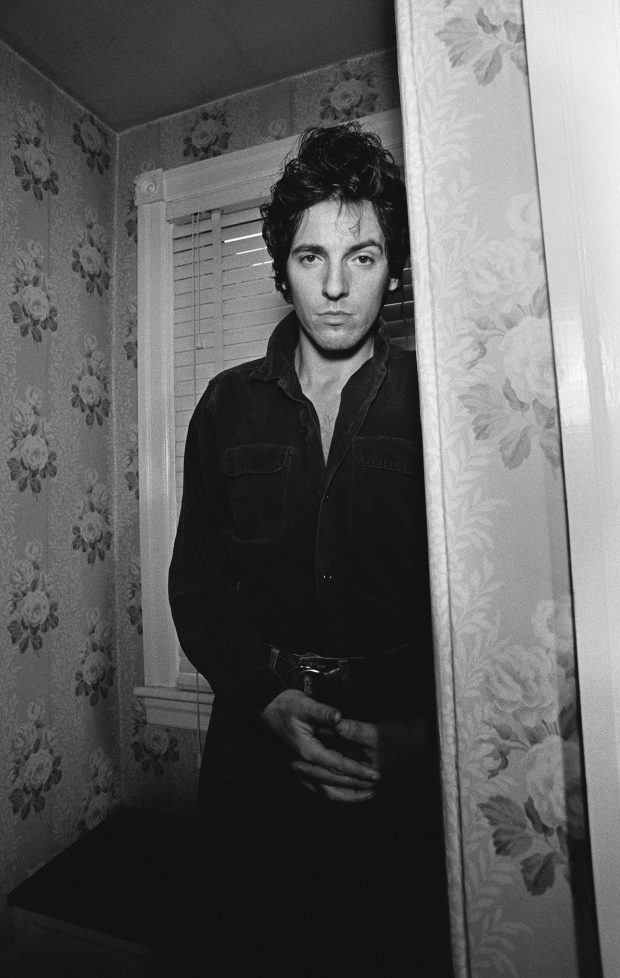

That speaks to how well The Boss and South Jersey photographer Frank Stefanko were simpatico. The front and back cover images for Darkness, with a tousle-haired Bruce standing against venetian blinds and floral wallpaper, gazing in the lens with a mix of world-weary ennui and quiet confidence, were actually shot in Stefanko’s home in Haddonfield, New Jersey, a cozy borough just 25 minutes east of Philadelphia. They were two of the first photographs Stefanko took of Springsteen, from a test shoot that would precede their main portrait sessions. And with The Boss presenting an everyman character in his poise – whether intentional or accidental — the image connected hugely with the songs he was crafting at the time.

As Stefanko told Pitchfork in a 2010 interview, “We were trying to recreate these middle America, working class families; guys that were looking for redemption. It could have been done in the 70s or 50s or even the 40s. The idea was that these people transcended time or space. But we were trying to get something to look like an old Kodacolor snapshot. There were a lot of black and white photographs taken in those sessions too which were very striking in their own right. But the idea of this color photograph that could have been a snapshot in somebody’s drawer worked for the album.”

As it turned out, many famous images of Springsteen were also taken in and around Haddonfield, by Stefanko. The artwork for The River. The cover of his memoir, Born to Run. This fall, Stefanko released his own book, a massive new photo collection called Bruce Springsteen: Further Up The Road. The book chronicles the two Jersey boys’ four decades working together, from the sessions for Darkness and The River through the Nebraska years and up to Springsteen’s tours in 2012 and 2016. It features photos, proof sheets, and lots of lore, and to commemorate the year they began working together, is released in a limited edition of 1,978 copies.

“Bruce was looking for a certain feeling, a certain look,” Stefanko said when I caught up with him via phone last month. “And to my great pleasure, the images I created were the ones that he felt represented the characters he was writing about.”

The cover art of Bruce Springsteen’s Darkness on the Edge of Town | photo by Frank Stefanko

The two artists connected through a mutual friend – Patti Smith. Stefanko and Smith are old friends, and attended Glassboro State College together. She moved to New York in the late 60s to pursue her writing career – which, famously, blossomed into a punk rock career as well – but they kept in touch. Stefanko remembers catching an in-concert special broadcast by Ed Sciaky on WMMR, where Springsteen played from The Main Point in Bryn Mawr. Stefanko was floored.

“I told her to to watch out for Bruce Springsteen, because he was going to be famous someday!” Stefanko laughs. “Not long after that, Patti saw Bruce at The Bottom Line, met him backstage, and said ‘you’re going to be famous someday, my friend Frank from South Jersey said so.’ That was the beginning of the connection.”

A few years later, Smith was working on Easter at famed New York studio The Record Plant while Springsteen was beginning the Darkness sessions at the same facility. While collaborating on “Because the Night,” Springsteen got to see portraits of Smith taken by Franceso Scavulo and Richard Avedon, Annie Liebowitz and Bill King. “It was all the great New York photographers of the time,” Stefanko remembers. “And then he saw the pictures I shot of Patti and he said, ‘Wow, who did this?'”

A few months later, Springsteen rang up Stefanko – “aaaayyyyyyy Frankie, let’s take some PHOTOS,” as the photographer recalls – and the working relationship began. Portrait shoots had already commenced for the record, some by Eric Meola – who famously shot the Born to Run cover – and some by lesser known artists, but as Stefanko recalls, those images were deemed too slick.

“He was looking for a new look,” Stefanko says. “And he said in his memoir, my photos best represented these new characters he was singing about on the album.”

During several days of shooting, Stefanko captured Springsteen in candid moments along the common streets of small town America. He leans up against a peppermint stripe barber pole; he tosses a toy football on the photographer’s front porch. He slumps in a broken phone booth in Shellow’s Luncheonette in East Camden, raising an eyebrow at the hand-written “out of order” sign.

If it seems like he had incredible access to one of the biggest stars in rock and roll – well, he kind of did. But two points to remember: Springsteen’s level of fame in 1978 was very different than it is today. And famously, he took a lot of time to get every detail of Darkness exactly as he wanted it, from the lyrics to the arrangements to the look of the cover.

“Because his celebrity wasn’t as great, his schedule wasn’t as tight as it was later, and he had a lot of time to work on this album,” Stefanko recalls. “We took a total of four days to work on the photos. He came down to my house in Haddonfield for two days by himself. The following weekend, he came back with the entire E Street Band. And then after, that he asked me to come to New York and do some shots on the rooftop of the Record Plant. When you’re shooting for four days, you can run a lot of film. So I did.”

Bruce Springsteen in Haddonfield, New Jersey | photo by Frank Stefanko | via ShoreFire publicity

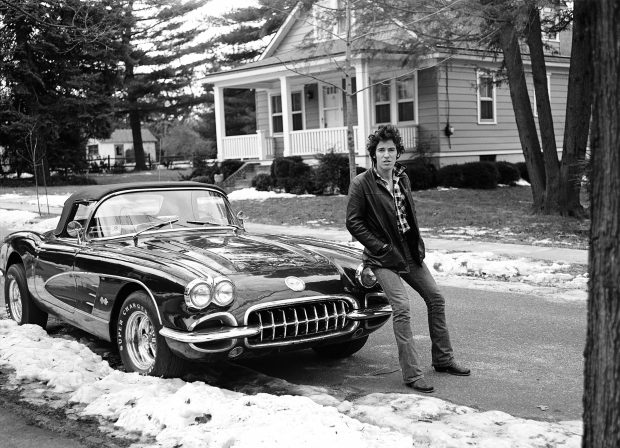

We see him sitting on the brick steps of a front stoop; we see him leaning on a shiny convertible parallel parked on the tree-lined streets and snow-covered sidewalks of suburbia — the image used on the cover of his book Born to Run. I asked Stefanko how Haddonfield of 1978 compared to Haddonfield of today.

“It wasn’t quite as trendy as it is now,” he says. “But it was still a very lovely town to live in. Parts of the town are very upscale and old – the town is almost 300 years old. Elizabeth Haddon settled that town before the revolutionary war. There were some elegant mansions, some very nice single homes. It covered the whole economic strata.”

It was a quiet town, too, and Stefanko says that the two were able to walk through the streets and work with relative anonymity.

“Relative anonymity, that’s the key,” Stefanko laughs. “Bruce always put on a pair of sunglasses when he went out onto the streets. So we’re walking down Kings Highway in the main part of town. People would look at him, look at me, and they’d shake their said and say ‘Nah, it couldn’t be.'”

Bruce was also somewhat distanced from the flash of national attention that greeted his previous album, due to a storied legal battle with a former manager that was drawn-out and strenuous.

“He had a three year layoff after Born to Run, and Darkness On the Edge of Town hadn’t come out yet. So people had sort of forgot about him, or didn’t know him at all,” Stefanko explains. “So this was an important album for him to get back on track and make sure every facet was done correctly.”

Thankfully, the two got on famously, and as Stefanko told Vanity Fair in an interview last month, bonded over a shared upbringing: blue-collar families, moms who are Italian married to dads who are not, and a mutual love of the Jersey Shore.

“There were lots of similarities, and it made for an immediate connection or comfort level,” Stefanko recalls. “So when we started working, there were no barriers. We just connected, and it’s always been that way. From the beginning, when he wasn’t as imposing of a character, even to April when we did a shoot to finish the book this year. It’s the same feeling, the same easygoingness, and we fell right into it.”

That statement begs a question: does Stefanko see Springsteen as imposing today? He pauses, considers, and then responds, “When we started, he was in his twenties, and I saw a street kid, just a working class guy who had a special talent. But you know, he was relatively uneducated – I think he went to community college – and he talks like anyone else you know. ‘Heeeey’ and ‘y’know,’ all that kind of stuff.”

Stefanko continues, “What’s happened over the years, because of his work ethic and because of his ability and drive to improve himself in all facets of things, not just music: he is very well-read, self-educated, he’s incredibly intelligent, he’s incredibly worldly – he’s evolved as much as you could with the stature and financial backing that he had, and he’s used it to the best of his ability. He’s paced himself and I’m proud of him. He hasn’t been tainted by the fame and money, compared to the number of people who have burned themselves out in this industry. He came from a working-class mentality: he wasn’t here for a flash in the pan, he’s here for the long haul.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8q3FYajY3sM

Bruce Springsteen is beloved the world around, for certain. He’s particularly beloved in Philadelphia, which I’ve always found unique – he’s from our neighbors in New Jersey, sure, but he’s actually from two hours north into the Garden State, much closer to New York City than he his to Philly. I ask Stefanko his take on the connection.

“I attribute that to very very much to two people,” he reasons. “David Dye and Ed Sciaky. They embraced his talent in the early days and promoted his work. And also the fact that Bruce was local in terms of being a ‘Jersey Guy’ and played places along the Jersey Shore, north and south, and little clubs Cherry Hill – there was a place called Uncle Al’s Earlton Lounge — and little clubs in Philly, like The Main Point, which was basically a coffee house, a folk club. … There was a lot of music in Philly and the local radio stations were playing this music that people related to and not the top pops.”

Some of the photos in Further Up the Road are from Springsteen’s tour stop at The Spectrum on May 26, 1978; these are contrasted with photos from 2016’s River tour stop at Wells Fargo Center on February 12, 2016. I asked Stefanko how shooting the recent date compared to shooting in 1978.

“I wished I’d had the equipment then that I had now,” he says. “I think I had an old 35 mm sears roebuck camera with a normal lens. I think I was sitting in the 12th row and dowing my very best to compose the shot. It was horrible, the lighting was bad.”

Photography has evolved by leaps and bounds in the decades since; Stefanko has been shooting digital since 2010, and he loves it. “It’s a whole other world. You can do so much more with the equipment,” he says. “When I shot the 2016 in Philly show, I had a tremendous professional Canon camera, the 5D Mark 3, I was using very high speed telephoto lenses where I could get close shots without being on top of somebody.”

He laughs again, recalling the spectacle of shooting rock concerts in 1978. “In the old days, at The Spectrum, you went to dance concerts and you had to elbow your way to the crowd to get as close to the stage as you could to get a good shot. You’d maneuver past the guy swigging a bottle of wine, past the people passing joints, you’d try not to trip over the bottle somebody had urinated in. It was a fight, it was bloody.”

And the energy and emotion of The E Street band and its fearless leader?

“Well, the man’s 68 years old, so he’s not really jumping like a mountain goat from one speaker to the next to the next to the floor, where he’s impacted his spine so much that he’s had to have disc replacement surgery in his neck,” Stefanko says matter-of-factly. “But I’ve seen him backstage before a show, and he’s pretty reserved and quiet. But once he gets onstage, whether it’s 1978 or 2017, all hell breaks loose. Maybe not the same energy from when he was a kid, but he still gives it all.”

Which, Stefanko reasons, is why he connects – that working class work ethic of going hard, doing your best, and pacing yourself.

“He’s touched a certain sort of person,” Stefanko says. “And there are a lot of them out there. He will endure.”

Bruce Springsteen: Further Up the Road is available now in its collectors edition via Morrison Hotel Gallery; click here fore more information, or to order. Check our more images from the book in galleries at Vanity Fair as well as The Guardian. And if you’re in New York over the holidays, swing by 116 Prince Street in SoHo, and you might just see some of Stefanko’s Springsteen images framed and on the wall.

Bruce Springsteen in Haddonfield | photo copyright Frank Stefanko | used with permission