photo by Yoni Kroll

Grave Images 2: Another musical trip around Philadelphia’s historic cemeteries

This is The Key’s second Grave Images article. Like the last one, which came out in July, this was motivated by an attempt to find things to do during the ongoing pandemic that are outside, interesting, and socially-distant. And if there’s one thing that can be said about graveyards it’s that they’re usually quite empty.

When I was a teenager I always read the obituary section of the newspaper because I found all the personal stories contained in those short paragraphs to be so absolutely interesting. It was a habit I picked up from my mom and grandmother.

As an adult I am, for better or worse, pretty familiar with death. Indeed, the final section of this article is about my friend Curan Cottman, better known as Ron Vega, who died on the 3rd of July. Also while I was working on this article the aforementioned grandmother, Betty Karlin, passed away at the age of 98. I was unable to go to her funeral because of the pandemic, which was crushing. I want to dedicate this article to her because I know she’d find it fascinating.

Lewis Redner (1915 – 1973)

Woodlands Cemetery

There are songs that are so ubiquitous that it’s hard to imagine that there was ever a time they didn’t exist. Christmas carols definitely fall under that category. They’re omnipresent to the point that even if you don’t celebrate the holiday and don’t think you know the words to the songs, when you hear those first few notes you’ll at the very least be able to hum the rest.

While a lot of the Christmas classics are actually pretty new — thank you Irving Berlin, everyone’s favorite Jewish-American holiday songwriter — some of those tunes go back a couple hundred years. While that might not seem that long ago, when it comes to songs that are still in the popular lexicon that is basically ancient history.

That brings us to “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” written in the big city of Philadelphia way back in 1868 by Phillips Brooks and Lewis Redner. Brooks, an Episcopal priest at Church of the Holy Trinity, did the lyrics — inspired by a trip to the Holy Land three years prior — and Redner, the organist at that Rittenhouse Square church for almost two decades, created the well-known melody.

Originally titled “St. Louis,” the song came together at the very last minute according to Redner in an interview he did a few years later that was published in Louis F. Benson’s book Studies Of Familiar Hymns:

“As Christmas of 1868 approached, Mr. Brooks told me that he had written a simple little carol for the Christmas Sunday-school service, and he asked me to write the tune to it. The simple music was written in great haste and under great pressure. We were to practice it on the following Sunday. Mr. Brooks came to me on Friday, and said, ‘Redner, have you ground out that music yet to ‘O Little Town of Bethlehem’? I replied, ‘No,’ but that he should have it by Sunday.

“On the Saturday night previous my brain was all confused about the tune. I thought more about my Sunday-school lesson than I did about the music. But I was roused from sleep late in the night hearing an angel-strain whispering in my ear, and seizing a piece of music paper I jotted down the treble of the tune as we now have it, and on Sunday morning before going to church I filled in the harmony. Neither Mr. Brooks nor I ever thought the carol or the music to it would live beyond that Christmas of 1868.”

Although Brooks moved to Boston to take on the rector role at the huge Episcopal church there, Redner never left the Philly area and is buried at Woodlands Cemetery.

Jim Croce (1943 – 1973)

Haym Solomon Memorial Park

It’s hard to believe that when Jim Croce died in a plane crash in 1973 he was just 30 years old. After all, in the almost half century that’s elapsed since that tragedy, Croce has become seemingly more famous despite the fact that there wasn’t a big treasure trove of material to release posthumously. Still, with songs including “I’ll Have to Say I Love You in a Song,” “Operator (That’s Not the Way It Feels),” “You Don’t Mess Around with Jim,” and of course “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown” Croce managed to cement his place in the American songbook in just a scant few years.

Something that a lot of people don’t know about Croce is that he was born in South Philly, raised in Upper Darby, was a college radio DJ during his time at Villanova, and is buried right outside the city in Malvern. He is a true Philadelphian and really should be mentioned in the same sentence as The Roots, Jill Scott, Patti LaBelle, Hall & Oates, and other greats.

While Croce was not raised Jewish, he converted when he married his wife Ingrid in 1966. According to an absolutely fascinating 2018 interview with Joseph Prouser, a rabbi in North Jersey and a huge Jim Croce fan, he became very interested in Judaism after meeting Ingrid but did not convert for her. You can read the whole article about the very Jewish nature of Jim Croce over here.

Croce is certainly the most famous person buried at at Haym Solomon Memorial Park, a Jewish cemetery about 40 minutes outside the city, and is very much the only reason a lot of people visit. His gravesite is a simple plaque in the ground, like all the other memorials at this cemetery. It’s covered in dimes fans have left in reference to a line in the song “Operator” from his 1972 album You Don’t Mess Around with Jim.

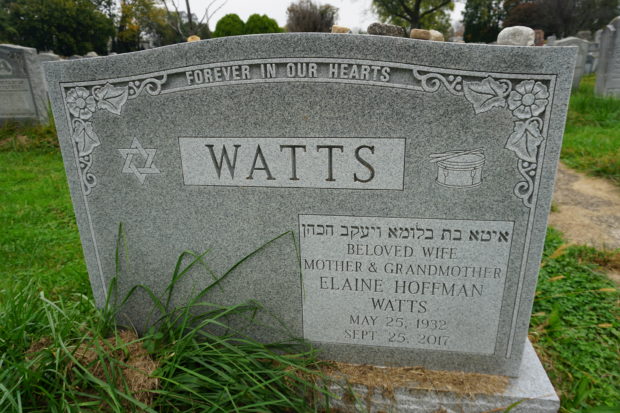

Elaine Hoffman Watts (1932 – 2017) / Jacob Hoffman (1899 – 1974)

Har Jehuda Cemetery / Mt. Sharon

When Jacob Hoffman moved to West Philadelphia from Ukraine at the turn of the 20th century, he brought with him the sounds and traditions of klezmer music. The style originated within the Jewish community in Eastern Europe and was very much meant for celebrations like weddings and bar mitzvahs.

A xylophonist and percussionist, Hoffman was a mainstay in Philly’s klezmer scene and played in bands throughout the city. He and his wife Bessie raised their children at their home at 63rd and Ludlow.

Jacob’s daughter Elaine was born in 1932. She would become an award-winning drummer and a noted klezmer musician in her own right. Her journey started in that Southwest Philly home. In a 2011 interview with NPR she recounted how, “It was a family thing. I bonded with my father that way. As a little kid, he used to take me in the cellar – not the basement, not the recreation center – in West Philly. And he would play xylophone. And he would put the sticks in my hand and he would say, ‘Play this.’”

While at the time women might not have been accepted as musicians, much less as drummers, much less in klezmer, Jacob Hoffman very much saw his daughter as an equal. It helped, as she pointed out in that interview, that he had no sons. It was not so much a feminist crusade as Jacob Hoffman wanting his kids to play music. Even so, Elaine ended up being the first female percussionist to graduate from the Curtis Institute of Music and went on to a career as an orchestral timbalist, which was almost unheard of at the time for a woman.

A similar story was told by her husband Ernie Watts in a remembrance published in The Key following Elaine’s death in September of 2017. He recalled how she ended up filling in for her dad for a performance of The Man of La Mancha: “Her father was the drummer for the band. The day before the show opened, he got sick, rushed to the hospital. No drummer. They asked him, ‘We need a drummer, can you recommend anybody?’ He said, ‘Yes, my daughter.’ She read the score through with the conductor the day before she opened. And when the show opened nobody knew the difference. She was a musician, not just a drummer.”

Still, she was basically shut out of playing klezmer due to it being a boys’ club. It wasn’t until the klezmer revival of the early 90s that Elaine began playing the music of her family in public again. Asked if that was something she felt resentful about, Elaine’s daughter Susan Lankin-Watts, a noted trumpeter, said in that 2017 article that, “Yes! She hated it. She hated it. Absolutely hated it. Misogynistic shit.”

Just as her father taught her, Elaine took on tons of students over the years. She was still teaching at the time of her death.

Elaine was buried with her drumsticks at Har Jehuda Cemetery in Upper Darby. Her father Jacob is interned at Mt. Sharon in Springfield.

Grover Washington Jr. (1943 – 1999)

West Laurel Hill Cemetery

Not only was Grover Washington Jr. an absolute beast of a saxophonist but everything he did was just so absolutely cool. Just watch this video of him playing his hit “Mister Magic” back in 1981 at the Merriam Theater, then known as the Shubert:

Say what you will about smooth jazz but this stuff is rocking!

That concert was about midway through a career that started in 1967 and ended with Washington’s tragic death in 1999 from a massive heart attack at just 56 years old.

Though he was born in Buffalo, Washington called Philadelphia home since he moved here in the late 60s. His love for the city was clear – he even dedicated a song from Winelight, his 1980 album, to Dr. J – and he was very much embraced by everyone here.

While Washington is known for all those funky R&B hits like “Just the Two of Us” with Bill Withers and “The Best Is Yet to Come” with Patti LaBelle, he was very much not stuck in any genre of music. In a 2017 interview that appeared in The Inquirer, his longtime bandleader Billy Jolly said that Washington “was completely open-minded. A New Orleans funeral march, a classical piece, dirty funk – for him, it was: Do it openly and to the best of your ability. He could play any tune – any – in the standard book.”

Washington is buried at West Laurel Hill and even his grave is cool. The memorial is engraved with two images, one of Washington and his wife Christine and another of him playing sax, of course.

Hy Lit (1934 – 2007)

West Laurel Hill Cemetery

Hy Lit’s grave reads RADIO LEGEND and that is not hyperbole in any way. Lit was a mainstay on the AM and FM dials for more than half a century, mostly in Philadelphia. Fifteen years since he was last on the air – and 13 since he passed away – Lit is still considered one of the greatest voices to ever grace our city’s airwaves.

There is very much a connection between Lit’s career and the rise of rock n roll as both a style of music and a cultural movement. He first got on the air with WHAT and WRCV in the 1950s and then, as the Philadelphia Music Alliance put it on their website, “He ascended to a Philadelphia phenomenon during the late 50s and 60s as one of the WIBBAGE Good Guys at WIBG (99 AM).” That ‘ascension’ might be an understatement, as Lit – known as “Hyski” on the air – was at one point getting an astounding 71 percent of the listening audience.

While he’s closely identified with the radio, Lit also found success on television in the 50s and 60s. There was the Block Party, Hyski A-Go-Go, and the Hy Lit Show. That last one was actually nationally syndicated and appeared in more than 30 markets, which is really cool.

Along with WIBG he’s also associated with WDAS, WPGR, and WOGL. It was during his time at WOGL that Lit discovered he was suffering from the early stages of Parkinson’s disease, something that the station used to limit his hours. Lit sued and there was a settlement but as part of that he agreed to retire. His last show was December 11th, 2005. He died less than two years later.

Lit is buried next to his wife Maggie in West Laurel Hill Cemetery.

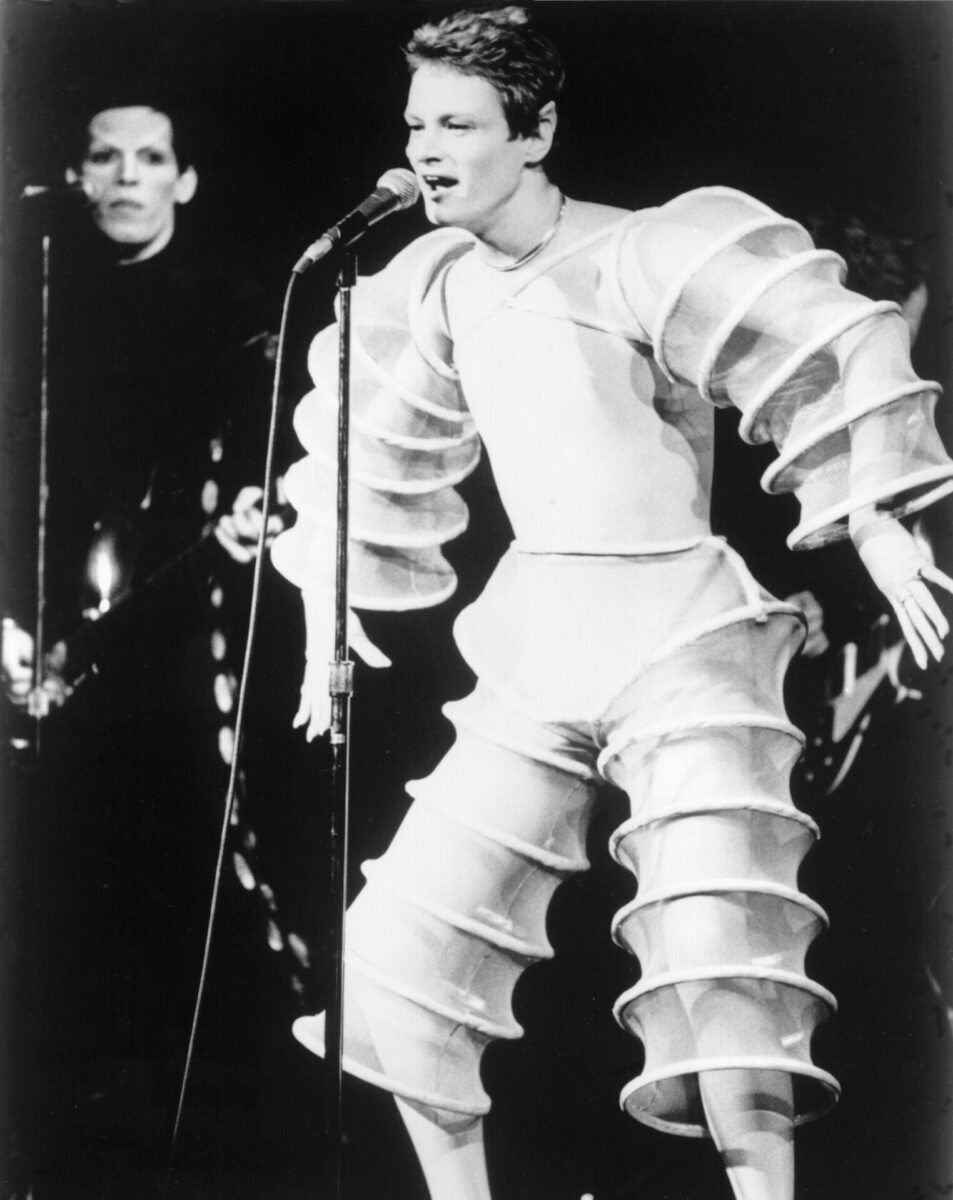

Jobriath (1946 – 1983)

Valley Forge Memorial Gardens

In the 70s, glam rock was huge on both sides of the ocean. There were the big names, of course – T. Rex, Sweet, David Bowie, Slade – but those are just the tip of the iceberg. Because of the burgeoning popularity of the genre, labels were putting out records left and right hoping to find the next “Jeepster” or “Ballroom Blitz.”

While glam was much more a British movement than an American one, that doesn’t mean there weren’t bands stateside doing the same thing. Some were straight up aping the established sound while others took what they heard and added their own flair – literally and figuratively – into the mix.

Jobriath was someone with a lot of flair. The King of Prussia native was an absolute force of nature in everything he did. He was born Bruce Wayne Campbell in 1946 and from a young age showed a ton of musical talent. At one point that even landed him an introduction to Eugene Ormandy, the conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra who was profiled in the previous Grave Images article.

He was drafted soon after high school, went AWOL, and landed in Los Angeles, where he got his first big break in the West Coast production of the musical Hair. While he received rave reviews for his portrayal of the gay Mick Jagger-obsessed teenager Woof – probably not a huge stretch for the openly gay Jobriath – he was soon fired for “upstaging” the other actors.

Jobriath’s second break came a few years later when he was discovered by Jerry Brandt, a promoter and manager who worked with Carly Simon, Chubby Checker, and many others. Brandt wanted Jobriath to be the next big thing and in 1972 signed him to a $500,000 two record contract for Elektra, an unheard amount of money at the time. There was a huge marketing campaign, giant advertisements with Jobriath’s nude form from the cover of the upcoming album in magazines and even on a Time’s Square billboard, and just so much hype.

Despite the fact that reality crept in and Brandt’s proclamation of “Elvis, The Beatles, Jobriath” didn’t come true, the 1973 eponymous debut got generally good reviews. Record sales, on the other hand, lagged. While a nationwide tour for the subsequent album reportedly did well, the band was dropped by Elektra midway through their dates, though they continued to play shows and bill the label for expenses. There’s a lot of information out there about these years but the go-to source really is the 2012 documentary Jobriath A.D.

By 1975 Jobriath had retired from rock n’ roll and, wanting to concentrate on acting instead. He moved into the rooftop apartment of the famed Chelsea Hotel in New York City and was doing a cabaret act he called Cole Berlin. Acting gigs were unfortunately rare.

By the early 80s Jobriath was sick with AIDS, which at the time was a new and very unknown disease that was seemingly only afflicting gay men. According to the documentary he found out he had HIV in 1982. He died on the 3rd of August, 1983 when he was just 36 years old. With his passing came one last bit of fame: he is known as one of the first major celebrities to die of AIDS.

Jobriath is buried at Valley Forge Memorial Gardens in King of Prussia. His plaque has his birth name on it, a cross, and a mention of the time he spent in the military. It’s otherwise unadorned.

Despina Lewis (1923 – 2016)

West Laurel Hill Cemetery

Just because Despina Lewis is not a name you recognize doesn’t mean she’s any less important than any of the other people profiled in this article. While she might not have recorded on any award-winning albums or been a longtime radio personality, she did something that’s arguably cooler: she taught piano for more than seven decades, first in schools and then out of the Upper Darby home she shared with her husband Fred, also a musician.

In a 2010 Delco Times article about the couple, Despina recalled how she started teaching in 1939 at age 15 and didn’t stop until she retired at 86. The two met for the first time when Despina was Fred’s instructor. They were married in 1957.

Despina must have been good at what she did because Fred went on to graduate from the Curtis Institute of Music and then he too became a music teacher, first in the Philadelphia School district and then at the Community College of Philadelphia. In the 60s he also performed with Frank Sinatra, Al Martino, and many more entertainers of that era.

There are thousands upon thousands of people who studied under Despina Lewis. Not all of them went on to be great pianists. In fact, it’s safe to assume that most of them didn’t, and that’s okay. As anyone who has learned an instrument when they were younger will tell you, it can be so incredibly rewarding even if you’re not that great at it. It’s also very much a necessary part of growth and education.

Despina Lewis passed away in 2016 and is buried in West Laurel Hill Cemetery. Her grave is adorned with the notation to an unnamed song.

Curan Cottman AKA Ronnie Vega (1991 – 2020)

Fernwood Cemetery

If I could tell Ron that I was including him in this article I know exactly what his reaction would be: “Bro, come on! I didn’t do anything that cool. Are you sure, homie? Grover Washington Jr.? Really?!” He’d ask me a ton of questions about everyone, laugh real loud, and then go back to telling me about his latest project or some band he saw play last week or whatever.

Ron was the lead singer of the rap rock band that shared his nickname – his full name was Curan Cottman but everyone called him Ron or Ronnie – and practiced in the basement of the house I moved into two years ago. He was a total sweetheart, a friend, and a kind of little brother to a lot of us in the punk and DIY scene that centered on LAVA Space, the community center and venue in West Philly.

If I had to sum Ron up I’d say he was both a dreamer and a bit of a pessimist, a combination a lot of us can relate to. You can hear that in the lyrics to his songs. Check out the video for “Therapy” and the line: “Millions of my dead ancestors walk with me / graveyards filled with kings, spirits talk to me / It’s like I’m going through futures of the past / going through depression sipping Henny in a flask.”

You can hear all of Ron’s music up on the Ronnie Vega Bandcamp. All proceeds from the sale of the digital discography are being donated to the Oshun Family Center: an organization that provides free therapy to Black residents of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Maryland “in the wake of the impact of the current conditions of both the COVID-19 pandemic which disproportionately is affecting the Black community, as well as the continued killings of Black people at the hands of police.”

There was a big memorial bike ride from LAVA to the Grays Ferry skate park a week after Ron died. It wasn’t the same as a memorial show – because of social distancing, we couldn’t even hug each other – but it was still nice to be in the company of so many people who loved Ron.

While Ron’s grave at Fernwood Cemetery in Lansdowne doesn’t have a marker on it yet, I took some pictures of the area where he’s buried. A family of deer were hanging out when I was there. Ron would have thought that was pretty cool, too.

Thanks to everyone who helped out, told me about their favorite graves, and passed along information and contacts. I’m especially grateful to Dana K for driving me to the burbs, the nice folks at the @corpse_altar Instagram account for the continued advice, and all the people who blew the first piece up.