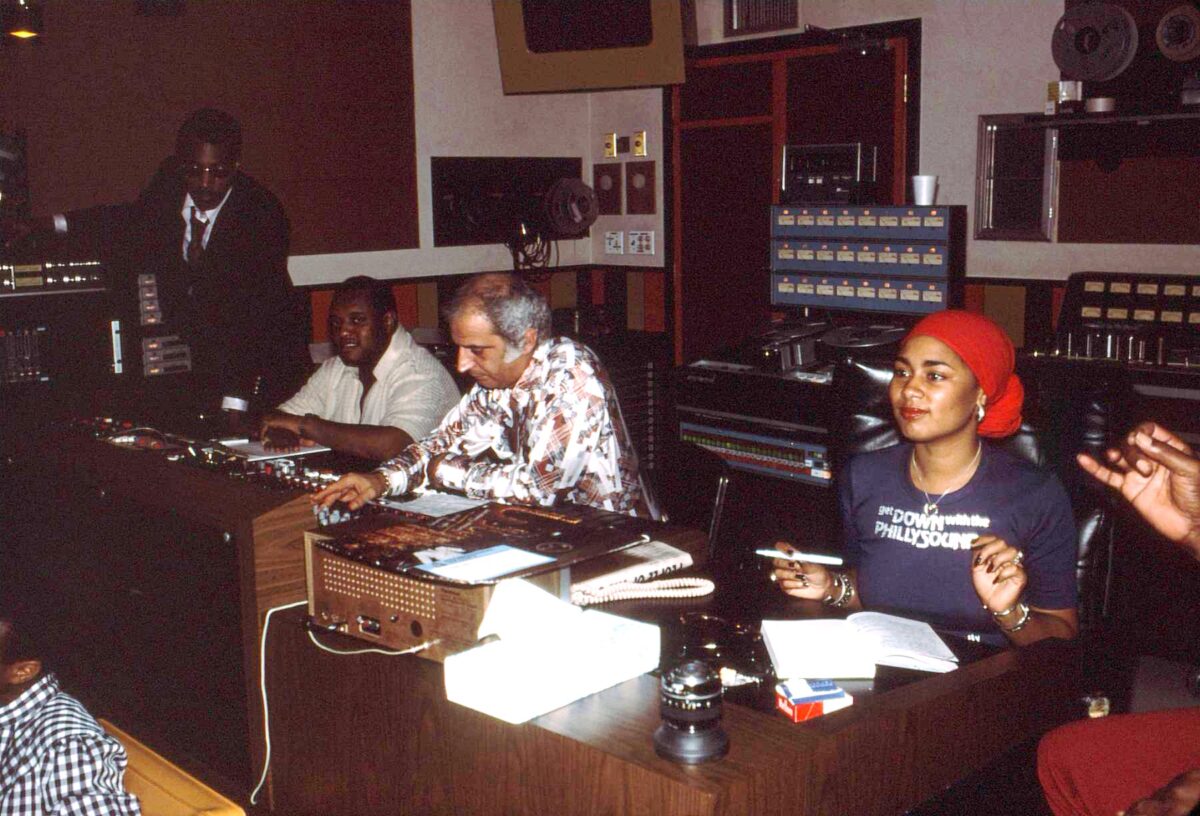

Sigma Sound Studios | photo by Arthur Stoppe

Sigma Sound Studios is unanimously added to the City of Philadelphia’s historic register

It’s official: Sigma Sound Studios, where so much music history was made, is now a historic place.

The Philadelphia Historical Commission, in a unanimous decision this morning, added the two-story grey brick building on Spring and 12th Streets to the City’s register of historic places. The vote came after about 45 minutes of community testimony speaking in support of the building, from musicians to academics to passionate members of the community.

The fate of the building that housed Sigma has been in limbo since a developer bought the vacated space in 2015 with plans to convert it into apartments. Nino Tinari, an attorney representing the property owner, spoke at today’s meeting, offering some pushback but also signaling a willingness to work with the commission and the community to make sure everybody is satisfied.

“We certainly have a great respect for Sigma Sounds and what it’s done over the years,” said Tinari. “It’s not a question of any personal animosity towards this application. … [The owner] will do everything in their power to accommodate the concerns of the historic commission to preserve a particular portion of the property.” But Tinari said the owner wants to see the building developed, and has received a zoning permit to do so. “I believe we can advance the interest of the committee and advance the interest of developing property the way it should be.”

Advocates for Sigma’s historic designation were not entirely unsympathetic to this. “I have experience as a real estate developer, so I do understand the parameters and complications of the gentleman who owns this building to attempt to monetize it,” said Tayyib Smith of Little Giant Creative. But Smith also spoke of how saving Sigma was an opportunity to correct a major failing in the city’s history.

“R&B and Black music in particular, and anti-Blackness, is the root of how Philadelphia culture is seen worldwide,” said Smith. “One of reasons we don’t have cultural spaces is because we have more than 100 years of anti-Blackness in our tourism and hospitality industry that deny this history.” Smith says working towards a preserved Sigma could fix “the lie that’s been told: that Philadelphia is all about stadiums, and fictitious figures like Gritty,” and Rocky, who Smith noted is an amalgamation of four different African-American boxers.

Through donations and philanthropic campaigns, Smith said he believes the resources to acquire the property are there, opening up space to “figure out something transformative and visionary to do with this property to correct the wrongs that have been done.”

The recurring vision for the space that came up through many of this morning’s speakers was a museum celebrating Philadelphia music history. Evan Solot of Philadelphia International’s MFSB house band first raised the idea when he read a letter signed by over a hundred industry professionals. This was echoed by James Gallagher, another person who worked at Sigma under producer Joe Tarsia.

Max Ochester of Brewerytown Beats has been one of the leading advocates for Sigma’s preservation, along with the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia; he joined many returning speakers who appeared previously in committee meetings, gave a rundown of historic happenings at Sigma over the years.

In 1973, Ochester said, drummer Earl Young played an innovative beat on Harold Melvin and The Blue Notes’ 1973 song “The Love I Lost” that would later become the backbone of disco music. (Alexandra Fiorentino-Swinton, a student at University of Chicago, said this is doubly resonant since “disco coming back in big way in pop…and through sounds pioneered with TSOP and other recordings, Philly pioneered that pop landscape.”)

David Bowie came to Sigma in 1975 to make the Young Americans album because he wanted to tap into the Philadelphia Sound, Ochester continued, and he shined a spotlight on singer Luther Vandross in the process. (Speaker Venise Whitaker also spoke about Bowie, noting that Philly Bowie Week launched after the rock icon’s passing in 2017, and saying that she hopes the holiday would include a celebration of Sigma’s preservation in 2021.)

Ochester also noted that Stevie Wonder booked recording marathon sessions in the building in 1977, widely considered his “genius period,” and The Roots tracked their first four albums at Sigma in the 90s.

Jack Klotz, a professor at Temple University’s Klein College of Media and Communication, spoke of how Philadelphia’s music was steeped in both European classical tradition through the presence of the Philadelphia Orchestra, as well as “a rich African tradition coming up, as Philadelphia is the first big city on the road north.”

“It was a beautiful marriage of cultures that intersected here in Philadelphia,” Klotz said. “A museum of some kind of designation on that spot could serve as a cultural touchstone, speaking to things Tayyib spoke about.”

Alan Slutsky, a musician who worked with Sigma over the years, said that the studio’s contribution was bigger than the 100s of hit records it gave birth to. “These are trying times we live in now,” Slutsky said. “In Sigma’s heyday, Philadelphia was also divided.” He referenced the city’s history of racism and injustice, from Frank Rizzo strip searching Black Panthers in public, to the MOVE bombing in 1985. “But at Sigma, a combination of Jews, Muslims, Catholic, Black, white, and Latinos worked together, respecting and loving one another, and that message of love traveled across the world. We need that message more than ever at the moment.”

When the Commission passed the motion to designate the building historic, Tinari, the attorney for the property owner, did chime in again question why, “with all this information, all this knowledge, why did this [attempt to have it designated] come about only after my client received its zoning permit? All this time period – from 65, the 70s, the 80s, the 90s, up until the time the building was abandoned. There was only some attempt to have building designated, and that designation took place across the street with a sign.” But Tinari said he hopes to see a plan developed that leaves everybody satisfied with the outcome: the community, his clients, and everyone who worked at the space.

Historical Commission chair Robert Thomas also echoed sentiments of balancing everyone’s desires, and reminded those at the meeting that the historic designation does not dictate use.

“What we heard today was not just a bunch of people saying ‘we want to save it, it’s a neat old building,’” Thomas said. “What a site like this represents, tapping into the incredible interest in this property is something that could be incorporated into another development of something considered valuable to the community at large, and to the property owner as well, and the commissioner will work with you on that.”