By nature of the music that it produces, hip-hop is a culture that is constantly engaging its own history. Through the magic of DJing and sampling, hip-hop music not only acknowledges the artifacts and sounds of the past, it uses them as raw material to build something new. With this summer marking the 50th anniversary of DJ Kool Herc and Cindy Campbell’s seminal party at 1520 Sedgewick avenue in the Bronx, New York, there’s been an unprecedented interest in the history of hip-hop. While all the ceremony, performances, documentaries, and celebrations honoring the culture’s pioneers have been truly lovely to see, the fact remains that the 50th anniversary has inevitably flattened the story of hip-hop’s birth and subsequent journey toward becoming a global culture. Charge it to the culture’s to symbiotic relationship to the music industry or not, the fact remains that the story being told as part of hip-hop’s 50th has been incomplete at best. With its heavy focus on big songs released by major label acts and easy-to-digest narratives, these celebrations have felt good, but ultimately lack the complexity and rigor that the culture deserves.

Following hip-hop’s emergence in the Bronx, there was a significant incubation period between the culture’s birth in the summer of 1973 and when rap music started showing up on records in 1979. When the Sugar Hill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” became a smash hit in 1979, the metaphorical genie had been let out the bottle. People had been rhyming over music, DJing, dancing and writing on walls forever, but hip-hop codified these disparate elements into something new, and rap music became the vehicle to deliver hip-hop to the rest of the world. Located roughly 100 miles south of the Bronx, it would not be a stretch to say that the city of Philadelphia was hip-hop’s first major stronghold outside of New York. Blessed with existent rhyming, DJing, graffiti and dance cultures prior to Herc’s breakthrough in 1973, Philadelphia was ripe territory for hip-hop to take root and blossom locally. By the end of 1979, when rap music was still alien to most of the country, Philadelphia had established a vibrant local scene and produced no less than three regional rap hits: Jocko Henderson’s “Rhythm Talk” and “Rocket Ship,” as well as Lady B’s “To The Beat Y’all.” While much of Philly’s early hip-hop history has been criminally under-documented, we do have one vital source to utilize when piecing together the story: memory. North Philly-born MC / radio host Frank Holiday was there in those early days, rolling with Philly pioneers like Strike Force, Disco Rat and Captain Boogie. Speaking with WXPN for this piece, Holiday’s power of recollection is sharp and encompassing as he gave vivid details about this crucial era in which hip-hop culture in Philadelphia was born.

with Disco Rat and Captain Boogie | courtesy of Frank Holiday

Growing up around 15th and Lehigh, Holiday’s childhood neighborhood was full of music and people trying to make it. Frank started working to get money early on, but at home, the power of art, music and the spoken word would offer him a brief glimpse at his future.

“Coming up from North, you always had a hustle,” Holiday remembers. “I used to shine shoes in bars. I used to work at the mom and pop stores and I was always a artist. I would draw, I was a big comic book fan, but my uncle Howard — who passed away recently — was my musical influence. He would have these old tape recorders that looked like reel-to-reels and he would play his music on that. He always had a nice sound system so, I would sneak in the closet and grab his albums.”

Another member of Holiday’s family, his Uncle Joe, lived in the basement of the house where he grew up. He says he would sneak downstairs in his room and listen to Richard Pryor. “My musical taste comes from the music of the 60s and 70s, really,” Holiday says. “Especially, in the 70s, it didn’t really have any color or gender. When you hear ‘Sara Smile’ for the first time on the radio, you ain’t thinking it’s two white guys. Boz Scaggs, you know, that’s a white guy. So when you listen to Bohannon, you don’t know he’s from the community that he’s from, or Sylvester or Luther Vandross; nobody cared about his lifestyle. It was just music.”

As Holiday entered his teen years, he would find his next great musical inspiration at area parties. When asked about the records that the DJs were spinning at these parties, Frank name-checks some of the funkiest tunes produced in the 1970s, such as Cymande’s “Bra,” “Mango Meat” by Mandril, The Commodores’ classic break “Assembly Line,” Cerrone’s “Rocket in the Pocket,” Herman Kelly & Life’s “Dance to the Drummer’s Beat,” and Issac Hayes’s “Breakthrough” from the Truck Turner soundtrack. A new scene was incubating throughout the city as skilled selectors in North Philly, South Philly, West, Southwest and Uptown brought DJ culture out of the clubs, and into neighborhood parks, block parties, rec centers and church basements.

“Around 77’, 78’ all the parties at that time really was in churches, in the basements of the churches,” Holiday says. “So, I would go to Our Lady of Mercy right at Broad and Susquehanna where the Rite Aid is at right now. The church up on 24th and Lehigh. I forget the name of that one. We had Our Lady of the Holy Souls on 19th and Tioga. So, our parties started there and then.”

Once hip-hop made it onto record in 1979, the impact of that first wave of rap records was immeasurable. Disco was still a predominant force in Black youth culture at the time, and the earliest rap records used the genre as their primary musical reference point. Because of this, the DJs at Philly hip-hop parties in this era were playing a mixture of disco, funk, rock and rap. Frank Holiday remembers how these parties and the records played there inspired him to get on the decks himself before he’d eventually pick up the mic.

“I was a DJ first before an MC. I was hanging with [pioneering Philly Hip-Hop crews] Sex Machine Disco and Strikeforce, I was actually a DJ for Strikeforce first. My mentors at that time were at Tan Tees. Who was Troy Wonder Boy, Superstar TK and MC T. They were my mentors,” Holiday says. “The one that taught me how to flow when I started rapping was a cat named MC Mastermind heard a song by Doug Henderson, aka Jocko. He had a song called ‘Rocketship.'”

Disco was out at that time; Michael Jackson had just came out with Off the Wall. And then Holiday heard ‘The Breaks’ by Kurtis Blow, and it gave him a new perspective. “I mean, everybody heard ‘Rapper’s Delight’ and it was cool. But when I heard ‘The Breaks’ and then [Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five’s] ‘Super Rappin’’ in the midst of all these other R&B songs and disco songs, I’m feeling the vibe.

photo courtesy of Frank Holiday

“I can’t sing for nothing,” Holiday continues. “I couldn’t carry a tune in a book bag . But I said, that I can do that right there. That’ll be easy. So, me and my guys on my block it was like, all right, we gonna form our own little group. And what happened was me and the homies on the block, we call ourselves doing our thing. We got our little set up and we seen this big red truck roll by that said ‘Disco Rat.’ [pioneering Philly DJ Nathan Robinson aka Disco Rat would pull up to parties in a small box truck painted in a vibrant red] I lost it. I’d always heard of Rat and I found out he was performing on [Disco Rat MC and member of the Tantalizing T’s] Troy the Wonderboy’s block on Smedley Street between York and Dolphin.”

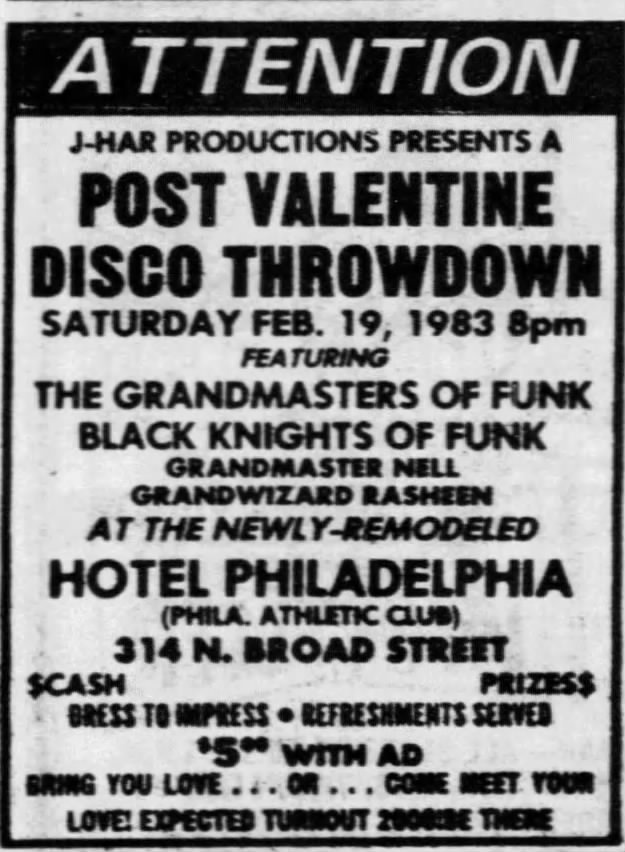

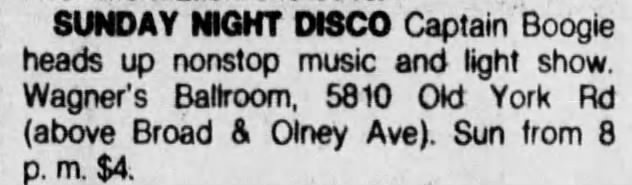

From rhyming on the block with his friends and developing his craft as an MC, Holiday would soon get a chance to be down with one of the giants of Philly’s early scene: Captain Boogie. Born Albert T. Grey Jr., Captain Boogie was an live sound engineer who would host events around the city at The Hotel Philadelphia on North Broad Street and a Sunday Night Disco party at the famed Wagner’s Ballroom near Broad and Olney. Frank speaks about Boogie’s influence on the nascent Philly scene and how he got down with him at the age of 14.

“People tend to forget, hip-hop started with DJing and soundsystems. That’s why Boogie was number one,” Holiday says. “Boogie had the biggest sound system, and everybody after that tried to catch up with him. FMD and Sex Machine was about sound. B-Force had a nice sound, but everybody followed Boogie. Everything was about sound first, then when they heard the rapping, that’s when rapping got involved with the DL. So, we [MCs] had to carry crates of albums just to get on the mic. So, after I got good enough, I’ll never forget it — February 14th,1980 at the church right on Germantown and Chelten [possibly First Presbyterian Church] — that’s where I performed my first professional show at. Mastermind took me up. He said ‘Yo, you wanna make some money?’ We go do a show. And he introduced me to Boogie. We came on right after Wonder Boy Troy and Grand Tone [member of the Grandmasters of Funk and DJ Diamond Kuts’ Father].”

The late 70s and early 80s were a truly fruitful time for Philly hip-hop. In the early part of the decade, Frank was among a small class of Philly MCs rocking parties around the city and advancing the craft of rapping before it had become a multi-billion dollar industry. Frank cites Astro Boy [Captain Boogie’s MC] as Philly’s first rapper and names folks like Parry P, Baby Sis [a Bronxite who rocked with Disco Rat], Cowgirl of Sex Machine, AJ And the Rock Brothers, Robbie B and Caesar [MCs for Grandmaster Nell] as his peers in Philly’s first generation of hip-hop. He also makes sure to shout out and acknowledge second gen MCs like Malika Love, Yvette Money and Steady B as standouts as well.

Whether you consider the Pop Art / Word Up label and their run of 12” singles that are still considered local classics, groups like Tuff Crew and Three Times Dope, and a vast community of DJs — Grandwizard Rasheen, Lightnin’ Rich, Cash Money, Jazzy Jeff, Spinbad, DJ Groove, Tat Money, DJ Thorpe and more — so many Philadelphia artists were displaying their virtuosity in the studio and onstage. Throughout the 80s — the decade when rap was evolving and expanding the most — the city was one of hip-hop’s major centers of activity. Today, Frank Holiday preserves these stories and educates on early Philly hip-hop through his YouTube channel and Facebook page. The amount of information that he has retained and freely shared with our community is staggering. He is intentional about getting the story right and giving everyone their due. As he recounts this complex and largely under-documented story of Philly hip-hop’s origins he any oversights that he may have made, addressing our city’s pioneers directly.

“If I forgot your name, charge it to my brain and not my heart,” Holiday says. “I got love for all of y’all. Some of y’all know me, some of y’all don’t. But the love is always there.”