In the annals of Philly hip-hop history, the After Midnight club holds a near-mythic status. Whether one considers it’s original location in the basement of an old factory building at 13th and Cherry Street, or its second location (inside a massive entertainment complex with its own skating rink) at 10th and Spring Garden Street, the mere mention of “the After Midnight” evokes memories of Philly hip-hop’s 1980s heyday. From being name-checked in songs by Black Thought and Bahamadia, to the stories of Philly legends Parry P and Jazz Fresh’s respective battles against LL Cool J and Big Daddy Kane, the After Midnight is an integral part of Philly hip-hop’s story. From the time the club was founded in 1984 to the close of its Spring Garden location in 1988, the After Midnight was not only host to some of the biggest names in rap, the club was an incubator for Philly’s nascent hip-hop scene. At a time when rap music had barely traveled outside of the tri-state area, and was rarely heard on the radio, the After Midnight was likely the first major all-hip-hop club in the country.

At the center of it all was a young DJ named Mike Maserati — formerly known as Mixmaster Mike — and his story connects some crucial dots between Philly’s rich disco, hip-hop and house scenes. Playing all-night DJ sets of some of the hottest new rap music, Maserati controlled the music as teens and young adults from all over the city (as well as New York and Jersey), flocked to the After Midnight to dance to the sounds of a new musical revolution. Speaking from his home in Philly’s East Falls section, Maserati explains that he got his start as a DJ long before the After Midnight opened, as he spent his youth carrying milk crates of records and equipment for his older cousin who would DJ at basement parties in the late 1970s. His cousin — also named Michael — taught him to DJ, and would also travel to New York to party at legendary clubs like the Paradise Garage, The Gallery and David Mancuso’s Loft, although Mike Maserati was too young to make those NYC trips.

“I was barely a teenager, still in middle school,” Maserati remembers. “I wasn’t even in high school yet. My parents wasn’t crazy about me hanging with him, but he wasn’t a bad influence or anything. He had all the latest music and would always love to do these parties or have parties at his house. Their house had the best finished basement and his mom liked to entertain. They were always having parties and he was always DJing.”

It was at these parties that Mike Maserati would be inspired to try his hand at DJing. Although those small, intimate gatherings in the basement were a far cry from the legendary clubs he’d play later, these parties ignited a passion that would last a lifetime. Maserati fondly recalls his cousin’s humble basement setup and the records he played.

“I remember they had a little room where he would have his stuff set up,” Maserati says. “It was like a little DJ booth, but it wasn’t really a DJ booth. It was where the water heater was and the heater for the house. But if you put a little table in the corner, it was a DJ booth. He used to have the speakers out in the basement area, and they’d throw the most incredible parties. That was kind of where I really, really caught the bug for doing that. Con Funk Shun, Teddy Pendergrass’ ‘Get Up, Get Down, Get Funky, Get Loose.’ When that came on, here’s everyone running down the steps to get on the dance floor. Cameo’s ‘Shake Your Pants.’ [Parliament’s] ‘Flash Light’ was another song. When that came on, people lost their mind.”

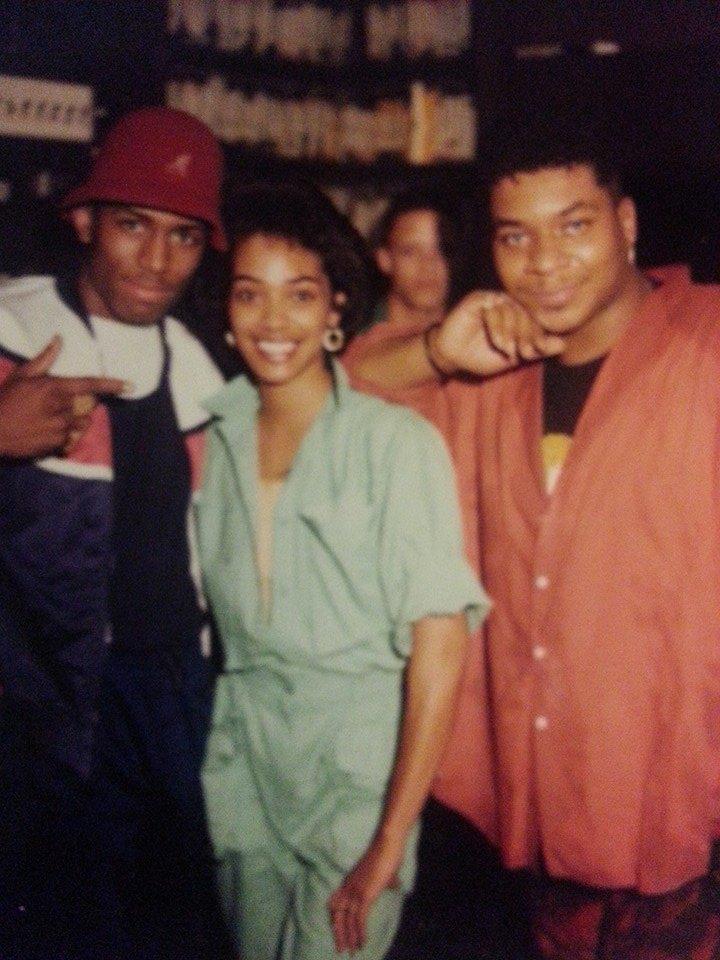

with Schoolly D | photo courtesy of Mike Maserati

From here it wouldn’t be long before Maserati would begin to explore Philly’s club scene. His cousin had let him try his hand at learning on the turntables and his curiosity led him to seeking out club nights where he could further soak in the sound of the nightlife.

“As I got a little older and was able to hang out a little later, I discovered after-hour clubs that were big back then that I didn’t even know anything about,” Maserati recalls. “One of my good friends that I used to hang out with was a guy named Tony Johnson. We used to go to a bar in Center City called Odyssey. It was on Delancey Street. It was a really cool bar and they played great music. We would hang out there all the time. So one night, we were always dancing and having a good time, having fun, and this guy kept talking to us. He was very nice and hanging with us, so the club was closing and I remember him saying to us, ‘Hey, where are you guys going afterwards?’ It’s two o’clock. The night’s over, but he’s was like, ‘no, no, no there’s an after-hours club called, Catacombs.'”

Catacombs was an after-hours gay club at 12th and Walnut. The club was located in the basement of the same building as The Second Story, a flashy private disco, considered to be the Philly equivalent of New York’s famed Studio 54. It was at Catacombs that Maserati would truly fall in love with club culture. Mike recalls seeing Philly DJ legends Billy Kennedy and David Todd rocking behind the decks at Catacombs. Kennedy would co-produce Direct Current’s “Everybody Here Must Party,” the tune that would become the backing track for Lady B’s early rap hit “To The Beat Y’all,” and DJ David Todd was a respected remixer and production partner to Nick Martinelli. Maserati recalls both DJs igniting the dancefloor with late 70s/early 80s disco classics like Geraldine Hunt’s “Can’t Fake The Feeling,” Denroy Morgan’s “I’ll Do Anything For You,” D-Train’s “Keep On,” and Taana Gardner’s “Heartbeat,” as well as Man Parrish’s early electro hit “Hip Hop Be Bop (Don’t Stop).”

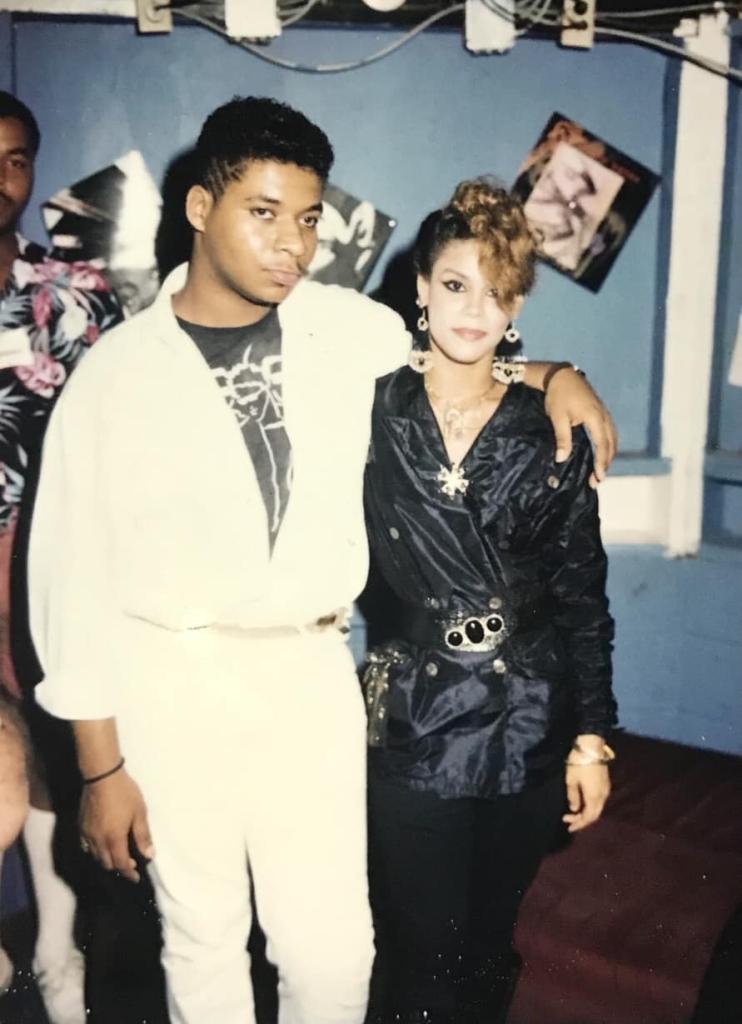

Mike Maserati with Mc Shan and Lady B | photo courtesy of Mike Maserati

“It was just magical. Once we went down those steps into Catacombs, we saw a whole other world,” Maserati says. “First of all, the sound system was incredible. I had never heard of sound system like that. They didn’t serve alcohol, so it was a lot of people having the best musical experience you can imagine. Most of the time there, I stood on the side with my mouth open because I just couldn’t believe what was going on. People are losing their minds to the best music all night long. I ended up going there for years and remember almost having an argument with my parents ’cause they didn’t understand why I would go out on Saturday night and not come home until six or seven in the morning.”

By 1983, a new club called Wild Cherry would open in the basement of a manufacturing building at 13th and Cherry. Wild Cherry was an after hours club that catered to Black gay clientele. It was at Wild Cherry that Maserati would get the chance to become more than a spectator to the club scene. Initially, Mike was hired to run the club’s lighting system, triggering the house lights in time with the music that the DJs played. Having passed a mixtape demonstrating his DJing skills to Wild Cherry’s manager, one fateful night, Mike would be called on to fill in for the club’s recently departed resident DJ.

Maserati describes the scene this way: “So I remember hanging in the bar area, talking to the guy that was getting the bar together. And I’m hearing this loud talking, someone arguing and I’m like, who the hell is arguing? What’s going on? Yeah. So I walk over to the dance floor area. It’s the owner and the DJ and they are in a heated argument and the DJ says ‘I quit!’ He grabs his and leaves as we’re getting ready to open. The owner came to me and said, ‘you’re on.'”

“I’ll never forget, my hands were shaking so much that I could barely put tonearm on the record. My hand is shaking so much that the needle was bouncing across the record. So, I just said to myself ‘Get yourself together. Take a few breaths and get it together. This is your moment.’ So, I pulled myself together and I did what I practiced all them years to do and that I have been doing already.”

After holding it down in the DJ booth at the club for some time, Wild Cherry’s management was feeling the pressure of having to compete with other similar clubs that were in the area. Wild Cherry’s owners and managers then decided to change the club’s name and musical format to capitalize on the emerging hip-hop movement. In 1984, the After Midnight was born and Mixmaster Mike would take on the role as resident DJ at the epicenter of Philly hip-hop nightlife. A large, multi-room space that took up the building’s entire basement level, the After Midnight was big enough to accommodate the droves of area youth that flooded the club on Fridays and Saturdays. Patrons would take a street-level stairway down to a small door where they were frisked by security. The door then opened up into a huge foyer and a pathway that led to the booth where party-goers paid between $8 and $10 (you paid more if you were wearing sneakers) to enter.

The club included a bar that sold snacks, juices and soda and the complex included a movie theater with a giant projection screen TV. Mike’s DJ booth even had its own air conditioner and a request line connected to it. Patrons would pickup the phone, press a button that lit up, signaling Mike and the patron could talk to him and request songs while he was in the booth spinning. Much like the earlier after hours disco clubs, the After Midnight was open from midnight to 10:00 a.m., although most of the crowd would usually be gone by 7. In addition to Mike’s marathon 7-hour DJ sets, he’d play live beats on the Roland TR-909 drum machine alongside the records he spun. The After Midnight was also the site of live performances from some of the era’s most prominent hip-hop acts from Philly and New York. When asked about the memorable artists that played at the After Midnight, Mike rattles off a list that reads like a who’s who of rap’s first golden era.

“Fresh Prince and Jazzy Jeff, Jewel T, Steady B, Three Times Dope, Cool C, of course, all of these people also just hung out at the club. Malika Love, Yvette Money. Run DMC, Beastie Boys LL Cool J, Roxanne Shante, The Real, Roxanne, Mantronix, Eric B. & Rakim…”

Mike Maserati with The Real Roxanne | photo courtesy of Mike Maserati

Feeling taxed by the grueling workload of spinning back to back nights every week, Maserati got the greenlight to hire DJ Terrell Clark to work Fridays. Despite the club’s success, the After Midnight was not long for Center City. There were some serious politics at play in the Pennsylvania State General Assembly that would radically alter the neighborhood around the After Midnight, eventually forcing the club to move. In 1986, the Assembly in Harrisburg approved funding for the construction of a new $500 million Pennsylvania Convention Center in the heart of Center City. As the construction of the Convention Center approached, business around the After Midnight began closing up shop and the club’s owner made the decision to move. On May 13th, 1988, the After Midnight would move into a 27,000 square foot building at 1004 Spring Garden Street. Despite its ambitious layout and popularity, the Spring Garden location would last less than a month.

Situated in close proximity to residences along 11th street, the After Midnight was immediately met with complaints from residents about noise, public drinking and drug use. In addition to an organized opposition from neighbors, the city’s Licenses and Inspections Department denied the club’s dance-hall license. Required for restaurants, bars, catering halls, night clubs and other gathering places with dancing and a lawful occupancy of 50 people or more, the license was necessary for the club to operate, and by the end of May, the After Midnight was no more. By this time, Mike had already established himself as the on-air DJ for Mimi Brown’s seminal Rap Digest radio show on WDAS.

Reflecting on his time at the After Midnight, Mike Maserati once jokingly proclaimed that “the diva ruled the 909 and the tables.” When asked about his experience as a gay man playing such a crucial role in Philly hip-hop history, Maserati recalls that he was treated with respect from audiences and his unique, disco-informed mixing style garnered respect from Philly’s notoriously critical DJ community.

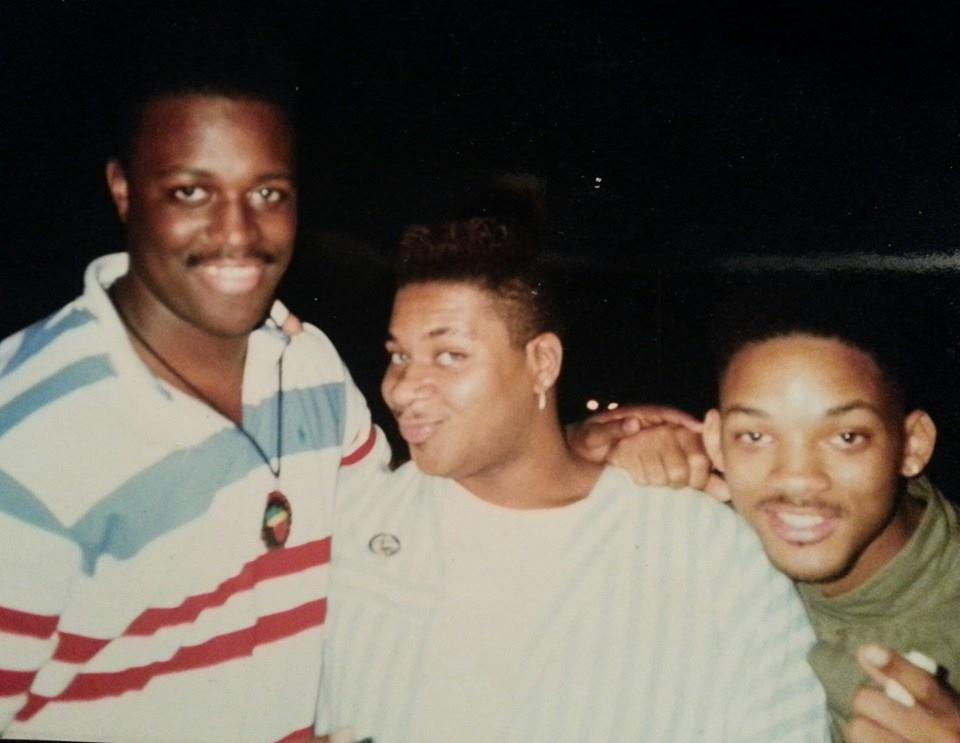

“You know, I’m sure some things were said behind my back, but not to my face,” Maserati says. “Everyone was always cool, from Will [Smith] to Cash Money and [Jazzy] Jeff. They were all scratch DJs, so they all admired the way I played hip-hop, ’cause they didn’t do that. They didn’t do no six, seven-hour mixed hip-hop sets. I was trained in riding mixes and holding songs together for a long time. I mixed hip-hop the way I mixed house. I would, play an instrumental of one song with the a cappella of another song and create stuff right on the fly. So, all of that kind of stuff made it exceptional. So again, I don’t remember anyone being outwardly disrespectful to me, to my face.”

Mike Maserati with Charlie Mack and Will Smith | photo courtesy of Mike Maserati

Following his days at the After Midnight, Mike would enjoy a long and storied career in music. From DJing at the Nile (the legendary Black gay after hours club at 13th and Locust) to his time in Philly’s House music scene, Mike Maserati’s story is the glue connecting many points of Philly club culture. Maserati is officially retired (although he still DJ’s occasionally), but he looks back on his time in Philly’s club scene fondly.

“It was an incredible time for music, for hip-hop and to be a DJ,” he remembers. “Meeting so many artists and entertaining the best crowds. I wouldn’t change that experience for anything in the world. Music is my life.”