Gail Ann Dorsey on learning from Bowie and returning to her own music

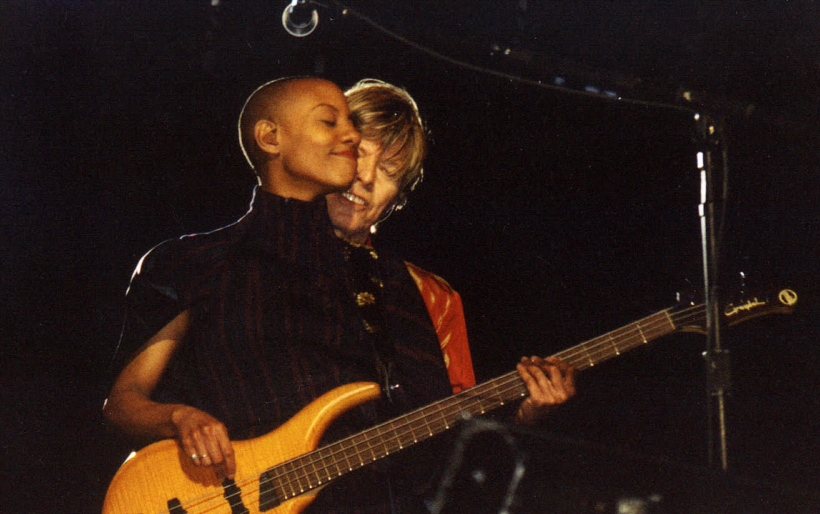

Gail Ann Dorsey grew up at 61st and Race in West Philadelphia, just eight blocks from the Tower Theater where she’d eventually share the stage with David Bowie. For Philly Loves Bowie Week, she talked with XPN’s Kristen Kurtis about her Philadelphia roots, her nearly two-decade run as Bowie’s bassist, and why she’s finally getting back to releasing her own songs.

Music was everywhere in 1960s and 70s Philadelphia, and Dorsey soaked it up. “Since I was like three, four years old, I was like, ‘I want a guitar. I want a guitar. I want to be able to communicate through music,'” she says.

But making it as a professional musician in the states wasn’t easy. The industry didn’t know what to do with her. “Sadly I felt like the US was always very… as a black woman, it’s like, ‘Well your music isn’t exactly… it’s not really R&B, but it’s not… we don’t know what to do with it.'”

So in 1985, at 22, Dorsey moved to London. There, she found government subsidies for gigging musicians and fewer questions about how to categorize her sound. “It was the first time I could make a living actually just playing music,” she says. “It was kind of like, ‘Do we like what we hear? Oh, cool.’… I was like, ‘Oh, wow, I don’t have to, you know, worry about those questions. I can just create what I want to create.'”

By 1995, she’d built up a solid resume touring with acts like Tears for Fears. Then one day, while working at Tears for Fears guitarist Roland Orzabal’s house, her phone rang. It was David Bowie, asking her to join his band for six weeks opening for Nine Inch Nails.

Dorsey knew Bowie’s music, his vocals on Young Americans convinced her that he was “one of the greatest male vocalists of all time,” but she wasn’t a superfan. Still, when rehearsals started in New York, she was terrified. She was about to play with musicians she’d admired on album covers since she was 14, including guitarist Carlos Alomar.

“I remember leaving the hotel that morning just shaking like, ‘Oh my God, what am I walking into? Am I good enough? Can I hold my own?'”

That six-week gig turned into nearly 20 years. Dorsey recorded on four of Bowie’s final albums and came to see the whole experience as an education. “It was like having… it’s like to me, like being an apprentice in a way to a really great creative genius, like it would be Michelangelo,” she says.

Bowie’s approach was about giving permission, not giving orders. “He gave all of us a real open space to play in, like kids,” she says. “He never put any kind of constraints on the creative aspect of making the music.”

He’d encourage the band to try everything, then strip things back. “He would always say, ‘You throw everything out and you take things away from it to let it reveal itself,'” Dorsey explains. When something clicked, his joy was pure. “He would just laugh like a child. He would just be so happy and he’d be like, ‘Woo!'”

Bowie and Dorsey also shared a thing for Philadelphia. He loved the city’s soul music history, and Dorsey says he’d get genuinely excited whenever a tour brought them back. “He’d always get a little nervous… when he was gonna play London,” she says. “Philly kind of was a little bit like that for him… He would always get really hyped up when we were about to come and play.”

For Dorsey, performing at the Tower Theater with Bowie brought things full circle. As a kid, her mother wouldn’t let her see him perform there. “When I was a kid and he played in Philly… my mother said, ‘You can’t go and see that guy. He’s wearing a dress,'” Dorsey recalls.

These days, Dorsey is focused on her own music again. She’s finishing her first album or EP of original material in 20 years, which includes her recent single and a new track called “Maybelline” coming later this month.

“I’ve kind of gotten to a point where I’ve played with so many people that I’ve really loved and it’s like, I don’t know where to go from here in terms of that,” she says. “I also think, you know, time’s getting on and I have some things I’d like to say musically.”

Bowie’s impact on her life is permanent, she knows that. “It’s like one person single-handedly has sort of changed the trajectory of my life in a lot of ways,” she says. “I will always be associated with the legacy of what he did.”